|

|

|||

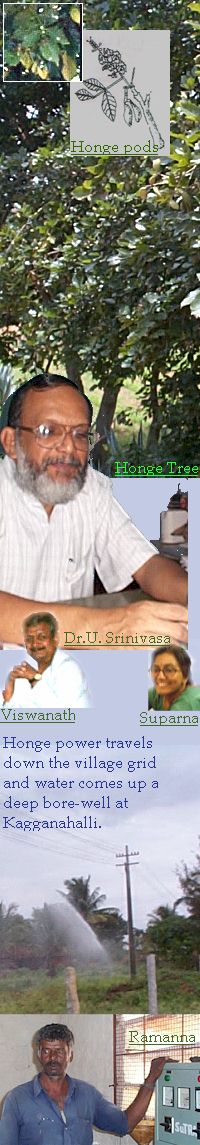

"Non-edible oils as biodiesels is the right solution for India," says Dr. U. Shrinivasa. |

|||

|

One evening in early 1999, Dr.Udipi Shrinivasa from the Indian Institute of Science, Bangalore was having tea with some locals in Kagganahalli village. He had for some years been investigating various strategies that would sustain continuous economic development of this semi - arid area. "Oh there is nothing much here," a villager was saying. "No river, no wells, no electricity; just hundreds of Honge trees and tonnes of seeds. Not much use now. Our grandparents used the uneatable oil for lamps!" Dr.Shrinivasa perked up! Useless? If it can burn in lamps, it can surely run diesel engines. After all Rudolf Diesel used peanut oil to run the first ever diesel engine. The adventure begins: Back in the Institute, he quickly extracted some oil, poured it into an engine and started it. Of course it ran! And ran well too. "It was a sobering moment," he says. "Here we were,- all scientists- looking at technical solutions like windmills, gasifiers, solar panels and methane generators for rural India, and we had not made the obvious connection with the potential of non-edible oils known from Vedic times as fuels." As he excitedly researched this 'bio-diesel' or 'eco-fuel', astonishing facts and scenarios came tumbling out. In the 1930s the British Institute of Standards, Calcutta had examined, over a 10 year period, a series of eleven non edible oils as potential 'diesels', among them the oil from Pongamia Pinnata ['Honge' in Kannada]. In 1942, during those dark war years the prestigious US journal, 'Oil and Power' had in an editorial euologised Honge Oil as technically a fit candidate to generate industrial-strength power. The Cinderalla oil: What happened then? War was over, oil fields were secure again, everyone got lazy and the petroleum industry got smart: it pumped out and flooded the world with fuels, at times cheaper than the cost of water. Honge oil fell from favour and waited like Cinderalla, for its prince charming. Even the rural Indian was moving away from remembered traditions: Kerosene had arrived in Indian villages. And yet a Honge oil economy did survive in India, though once removed from direct contact with people. Dr.Shrinivasa estimates that the size of trade in Honge oil['Karanji' in Hindi and 'Pungai' in Tamil] controlled by the Bombay commodities market is 1 million tonnes feeding mostly soap making and lubricants industries. In Warrangal, Andhra Pradesh, the Azamshahi Textile Mills, set up by the Nizam of Hyderabad in 1940, generated all the power needs of the factory using non-edible oils until its recent closure; and it had surplus power left over for the city's needs! However the Honge is a much ignored tree now. It grows on regardless, waiting for its virtues to be re-discovered. It is a hardy tree that mines water for its needs from 10 metre depths without competing with other crops. It grows all over the country, from the coastline to the hill slopes. It needs very little care and cattle do not browse it. It has a rich leathery evergreen foliage, that is a wonderful manure. From year-3 it yields pods and production is a mature average of 160kG per tree per year from year-10, through to its life of 100 years. Ten trees can yield 400 litres of oil, 1200 kg of fertiliser grade oil cake and 2500kg of biomass as green manure per year. Quick economics: Dr.Shrinivasa ran through some quick numbers. A litre of Honge was equivalent in performance to a litre of diesel. If the farmer collected the seeds free from his land, had it milled and sold the oil cake at Rs.3 per kG, the cost of oil to him was Rs.4 per litre. [The cost of diesel is Rs.18 a litre today.] If he bought the seeds at Rs.3.50 per kilo, the cost was Rs.9 per litre and if he bought the ready oil from the market it was Rs.20. The potential to drive the rural economy, make it autonomous and put some cash in its pockets was obvious. "We are mindlessly increasing food grain production without caring to see how the poor would buy them. That it is why food rots and people go hungry. If the power and fertiliser needs are met by Honge, villages would have cash surpluses," says Dr.Shrinivasa. In fact the opportunity is enormous for the country's macro-economy too. "...30 million hectare equivalent [planted for biodiesels] can completely replace the current use of fossil fuels, both liquid and solid, renewably, at costs India can afford," says Dr. Shrinivasa. Our oil bill is $6 billion a year; we can put a third of that cash in the hands of rural Indians, have our oil needs met and save the two thirds. Do we have the land? Sure! Currently about 100 million hectares are lying waste in India. Cost? About Rs.1000 crores per year for 20 years and we should become self-sufficient forever in oil. Proving grounds: The idea had to move from paper to the ground. Two breaks came his way. The first was from the industry, always quick to spot an opportunity. Dandeli Ferroalloys [Dandeli Town-581 325, Karnataka] established in 1955,is a heavy consumer of electricity. Power forms 60% of their variable costs. P.V.Jose of the company read an early press release about Dr.Shrinivasa's findings on Honge oil and got in touch with him. Coordinating with Dr.Shrinivasa, Dandeli converted all five of their 1 megaWatt diesel engines to run on biodiesel. [Jose reported in Feb., 2001 that they had generated 760,000 kWH of energy entirely from Honge oil. And they are continuing the usage.] The second break came from Karnataka's Rural Development and Panchayat Raj department. A sanctioned fund of Rs. 278 lakhs was allowed to run a Honge oil programme in seven villages around Kagganahalli. Dr.Shrinivasa prepared a master plan and has been executing it at Kagganahalli. The full weight of current scientific arts was brought to bear on India's rural development. Rs.200,000 was spent on sourcing satellite images to identify fracture lines and from them, deep water sources were identified using electrical sensitivity measurements. 20 bore wells of depths varying from 200' to 300' were drilled in the project area spread over 40 sq.kM. Submersible pumps were let into the wells and a project-level 440 volt grid was created to power the pumps. At the power station two 63 kVA generators stood waiting for Honge oil. A 20kM network of 3" pipelines was buried underground with outlets at various farm-heads. Honge seeds were collected from the project area, taken to a miller at a nearby town. The only processing done on the oil was to filter the detritus that could clog the fuel pump. Ramanna, a local mechanic recruited for the project poured the oil into the engine and pressed a button. Energy flowed through the project grid, charged the pumps and water sprayed out of a rain gun. For the first time ever in history Kagganahalli witnessed a source of water other than rain. Brought that too, by the produce of that very land! Two visions: Right from the start Dr.Shrinivasa was adamant that water had to be paid for. "Pamper them and you ruin them," he believes. Water was priced competitively at Rs2.50 per kLitre. And the farmers, albeit with some theatrical moans, began to buy. In the last 18 months the fields of Kagganahalli have produced watermelons, mulberry bushes, sugar cane and grains with a confidence that water was assured. So far 40,000 kLitres of water has been sold. Not a single litre of diesel was bought! Dr.Shrinivasa has his visions fixed wide and far. For Kagganahalli, he asked himself how the growing demand for water was going to be met. Thus began the scheme to manage the watershed. Already a stream has become perennial, charged by check-dams. Afforestation of the Huliyurdurga hill nearby has seen small game arrive. Tree plantation programme grows apace. Cash incomes from seed collection and wage work opportunities are beginning to increase. An information centre will soon be ready at Huliyurdurga to impart training to groups from other parts of India. [contact details follow] For the country as whole, he grows misty with his vision. "Sir, the economics are compelling," he says. "We get green cover, environmental rewards, local incomes and nation level independence. I have not drilled through the finer details. We could easily put the oil cake through digesters that would yield a rich fertiliser slurry, methane and drop costs further. The green cover would induce happy micro-climates and increase water resources. It is all so do-able." Nothing quixotic here. Biodiesel investigation is serious stuff worldwide [read more at this link ]. Only in the west the accent has been on vegetable oils [which are far too valuable in India's kitchens] to run automobiles. Dr.Shrinivasa's thrust on the other hand, has been to use non-edible oils to ignite a process of rural enrichment. Biodiesels have many advantages. They are cheap and renewable, they disperse profits, are safe to store [due to a high flash point], need nothing new to be invented to run engines, are kinder on the engines, have a long shelf life, are biodegradable, release no more carbon di oxide than the trees originally consumed and have cooler, clearer exhausts. And to the delight of many investigators the exhaust from an engine on biodiesel "smells of pop corn and french fries!" Why do they bother?: In N.Viswanath the project has a passionate evangelist. An engineer by training, he is an able media activist. Suparna Diwakar is a bubbly consultant. And Dr.Shrinivasa is the unassuming leader of few words with an unassailable conviction. Yet some 30 years ago he grew up in a modest family of fishermen in a small town called Udipi. It was even smaller then than now. The first hop out of his town was into the new institute of technology at Chennai. Since then, a life in academe. Why should he bother beyond the routine of a withdrawn family centred life? He is obviously not personally affluent and yet he dreams of riches for India. How come this supposedly feeble land produces people like him. He and his team are a part of the little known good news about India. If you suspend your cynicism you will find them here and there. Not too many but enough. Dr.U.Shrinivasa, N.Viswanath or Suparna Diwakar SuTRA [Sustainable Transformation of Rural Areas] Dept. of Mechanical Engineering Indian Institute of Science Bangalore 560 012 Karnataka

fax: 91-080-360 2435/360 2993 tel: 91-080-360 0080/309 2331 email: udipi@sutra.iisc.ernet.in / udipi@mecheng.iisc.ernet.in September,2001

|

Updates:

|

||