Story link: http://www.goodnewsindia.com/index.php/Magazine/story/umendra-dutt-and-kvm

In 2001, Jarnail Singh, a recently retired schoolmaster of Jajjal village in Punjab's Malwa region, began a macabre hobby. For about 5 years he had frequently been within earshot of villagers in small subdued huddles: "It was cancer", they would whisper and roll their eyes about as though to spot a lurking devil.

Was it actually at large, scything through people or was it all just rumour? Jarnail Singh decided to keep a meticulous record of cancer deaths. His list began to grow ominously. Within the next year, the village of Harkishanpura publicly advertised that it was offering itself entire, for a distress sale as its economy had collapsed, following loss to cancer of a majority of its agriculturists.

What could the matter be amidst the miles of green fields, in the home of India's Green Revolution? How could sturdy, prosperous, hard-working Punjabis be felled with such ease? When Jarnail Singh released his statistics, the ground under paradisal Punjab rumbled. Soon the connection was made between the cases of cancer and the drinking water polluted with leached agricultural chemicals

This story is not about that event. The depth of the problem is well detailed here. Our story is about Umendra Dutt, how he reacted to the news and how what he is doing is the only thing you can do about any problem: take responsibility for the solution and look for people to share that responsibility.

Umendra Dutt's grandfather Pandit Hiralal Sharma was of the heroic stock of his times, a stock that Gandhi produced out of ordinary men. Pt. Sharma had quit a lucrative government job heeding Gandhi's invitation to join the movement for non-cooperation with the British rule. Soon after Independence, the family had moved from Rawalpindi, now in Pakistan, to Ferozpur where Umendra was born, in 1962

"I did everything but study in school; I hated the class room," says Umendra. He organised sports, theatre and music events. He played hockey, painted and was fond of writing. He imbibed nationalism from the portraits Chandrasekhar Azad, Bhagat Singh, Sukhdev and Rajguru that hung from the walls of his home and their legends that lived in the bazaar.

And he was a serial runaway. "I kept going away, to various places, mostly religious centres," he says. Finally when he was about 14 and went missing for four months, the family at last got the message about formal schooling. The search party tracked him through Banaras, Hardwar and found him finally in Nemisharanyam.

"Do what you want, but stay at home," conceded his father Har Dutt Sharma, a clerk in the Life Insurance Corporation. Umendra completed his Masters in Hindi via a correspondence course and developed a facile writing ability. And he joined the Rashtriya Swayam Sevak Sangh [RSS] in 1981 and rose to be a Pracharak. The role suited the wandering, nationalistic communicator in him.

For two years he was a full time activist of ABVP, the students wing of the RSS. "Our response to every issue had to proceed from just two prescribed contexts: partisan politics and India's hoary past," he says. He gained many things in the RSS: the skill to motivate and organise people, discipline and frugality in personal life, commitment to assigned tasks and the friendship of many sincere people. But he also sensed he was missing something. In the entire RSS -which was full of dedicated people- he admired just three men: Dattopant Tengadi, Nanaji Deshmukh and Eknath Ranade. What was it about them that drew him? He had no answer that amounted to a lesson.

Between 1992 and 2002, Umendra was posted in Delhi, to edit and publish the Swadeshi Patrika. It was a magazine to propagate arguments against the so-called 'economic iiberalisation', a cunning euphemism for a policy that would stymie micro initiatives of Indians. Work as a journalist led him one day to Anupam Mishra who Umendra thinks is one of the great living Indians who should be heard widely. Mishra told him that any work that strives for change must be rooted in two things: party-neutral politics and spirituality. Politicians should be cultivated but across party lines. The successes of Tengadi, Deshmukh and Ranade was at once explained. They had friends and admirers in every political party because their work had transcended the narrow RSS ideology.

When Harkishanpura offered itself for sale because its resources- natural and human- had depleted, the cancer scandal played out along predictable lines. Journalists raised the noise level, legislators visited the scene, the government ordered an investigation and finally the Pollution Control Board confirmed the obvious: extensive pesticide use had polluted the drinking water. The government banned some pesticides and promised safe water and treatment for cancer. And thus it has came about as a final solution, that clusters of stricken rural folk, daily wait on Platform No.2 of Bhatinda junction for the train they have come to call "marizon ki train", the Cancer Express to take them to a hospital in Bikaner.

A puzzled Umendra walked away and started to think it all through. He too had reported the story, but where did the story really begin? The Malwa region of the Punjab consists of 12 districts [Firozpur, Moga, Ludhiana, Sangrur, Barnala, Mansar, Fazilka, Bhatinda, Muktsar, Faridkot, Patiala, Fategarh Sahib]. Historically it had practiced rain-fed agriculture, growing wheat, pulses and millets. During the Second War, Revenue Department officials seduced them to grow cotton, which brought money instead of mere health and food. Then in the 1950s waters from the Nangal Dam reached almost everywhere via canals. Shortly thereafter came the Green Revolution with magic seeds, instant fertilisers and a buffet of pesticides. What a feast the farmers made of it all. Money and concrete houses were sprouting everywhere. Women who were such an influential, integral part of farming were sent home by machinery for everything. Life and culture which were a part of food growing were separated by regimented crop production.

Unseen by all, chemicals leached into water, escaped into the air. People ingested them into their happy bodies as they celebrated their prosperity. Everything seemed fixable, including health, as long as one had money. Oh no don't just blame the government;everyone was in it. Your brother sold the fertilisers, and your uncle, the pesticide, his son in the government pushed the seeds, her daughter got a job as cancer nurse and my cousin has a busy medical shop. And doesn't our rich relative in the big city have a agro-chemicals factory to which flows huge government subsidies? Children sang out praising dams and factories as temples of modern India and the minister gave awards for bumper harvests. Everyone was part of the problem. Though the connections were obvious, no one wanted to see them.

Umendra Dutt recalled Anupam Mishra: Once you shed ideological fixations you will see the only thing worth caring for is the environment. He decided the solution cannot come from the government or agitations against it, but from the people themselves. People must experience convincing results, and then they will vote without loyalty to any party but only for what they know is good. His mission would be to promote micro-successes.

He quit Delhi and moved to Jaitu, near Bhatinda, a town of noisy streets lined with pesticide and fertiliser shops, open drains and vehicles racing about everywhere. He also quit the RSS; from now on he would belong to no party but befriend all parties in furtherance of his cause. He formed the Kheti Virasat Mission [KVM] -Mission for Traditional Agriculture- in 2005. The idea was to contact farmers, in ones and twos, persuade them to experiment with natural, traditional practices, to value quality and health above money, to become successes that others would emulate. He knew it was an unequal fight against the chemical monster that stalked Punjab but there was no other way to begin.

He brought natural farming evangelists from elsewhere in India and had them conduct workshops for farmers. Manohar Parchure, Priti Joshi, Subhash Palekar, Subhash Sharma, Suresh Desai, Kavita Kuruganti, Sudhirendar Sharma, Dr G V Ramanjaneyalu, Davinder Sharma, Deepak Suchde and many others presented gentler ways with growing food. A whole generation and more in Punjab had become unaware that food can be grown with cattle manure and crop rotation instead of fertilisers, heirloom seeds instead of hybrids, mixed cropping instead of pesticides, mulching with residual biomass, patterning action based on seasons instead of endless water. Now they were being nudged to experiment. The younger ones were incredulous but curious, and the older ones quietly reconnected with the times of their childhoods.

Umendra's great assets are his skills as a communicator, a persuasive way with people, a passion for his cause and his transparently simple, open way of life. He is single. KVM's office, guest room, and his home are all in a 300 sq.ft walk-up from a dusty Jaitu street. The main windowless room has a cot, a computer, a couple of chairs and heaped bundles of publications. From here he publishes his magazine 'Balihari Khudrat', here he meets his steady stream of visitors and here he retires for the night often giving up his cot to a visitor. The kitchen can fit just one person at a time and the washroom is even smaller.  The second room -better than his, with a window- is a dorm for volunteers. He or KVM own no transport. His operations are driven by donations, publication sales and a confidence that money will somehow arrive.

The second room -better than his, with a window- is a dorm for volunteers. He or KVM own no transport. His operations are driven by donations, publication sales and a confidence that money will somehow arrive.

Ajay Tripathi, 51 is a family man with responsibilities. "And therefore his sacrifices are greater than any of ours," says Umendra. Tripathi's association with Umendra began in 2004. He is a researcher, ideologue, back-room man and a strong believer in KVM's work. He commands respect not just because of his knowledge, skills, abilities to communicate or hard work. Umendra says Tripathi has embraced poverty as a positive way of life. He is a role model of dedication to the KVM team.

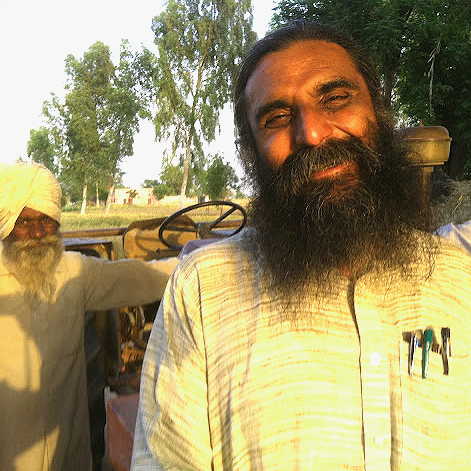

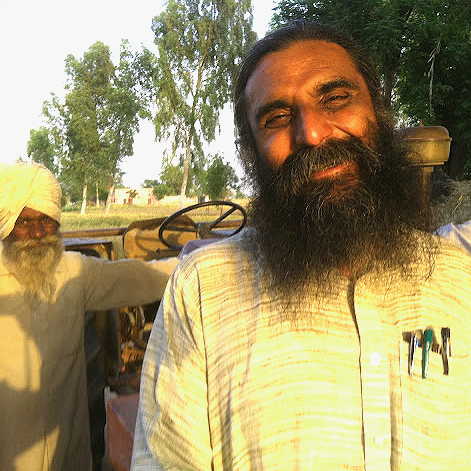

Gurpreet Singh,30  works as an organizer of KVM programmes. He met Umendra in 2005 while working for Pratham, which is an education outreach. "He promised me a good salary. It was an easy promise for men like him to make because they have no money but all the confidence! I would be paid as and when KVM got some money but I went for months without salary, pretending at home to be on a good wicket," he says with a big smile. He left for a steady job because he was getting married but Umendra blithely kept asking him to come back because there was much to be done and "money is no problem". Finally he couldn't resist coming back: "Now the pay is a bit steadier but it doesn't matter any more; the work does," he says, as Umendra sits nearby nodding and beaming.

works as an organizer of KVM programmes. He met Umendra in 2005 while working for Pratham, which is an education outreach. "He promised me a good salary. It was an easy promise for men like him to make because they have no money but all the confidence! I would be paid as and when KVM got some money but I went for months without salary, pretending at home to be on a good wicket," he says with a big smile. He left for a steady job because he was getting married but Umendra blithely kept asking him to come back because there was much to be done and "money is no problem". Finally he couldn't resist coming back: "Now the pay is a bit steadier but it doesn't matter any more; the work does," he says, as Umendra sits nearby nodding and beaming.

Amanjot Kaur  is a bubbly Sikh girl in her early twenties. She applied to KVM for an internship in 2010, soon after graduating from Punjabi University, Patiala. And has stayed on. She comes from a traditional family, -her father is an auto mechanic- where it is unusual to send young women to live alone and work. On her visits home she is itching to get back to Jaitu. Her job is to get village women to start kitchen gardens, revive grandma's recipes, include millets in diet, to organise seed exchanges and discussion groups. "Oh, I expect and accept my parents will find me a groom one day soon," she says. "But the marriage is on only if he accepts my work with KVM will continue," she says with a toothy grin.

is a bubbly Sikh girl in her early twenties. She applied to KVM for an internship in 2010, soon after graduating from Punjabi University, Patiala. And has stayed on. She comes from a traditional family, -her father is an auto mechanic- where it is unusual to send young women to live alone and work. On her visits home she is itching to get back to Jaitu. Her job is to get village women to start kitchen gardens, revive grandma's recipes, include millets in diet, to organise seed exchanges and discussion groups. "Oh, I expect and accept my parents will find me a groom one day soon," she says. "But the marriage is on only if he accepts my work with KVM will continue," she says with a toothy grin.

Working with little assured money [-except for some steady funding from the Centre for Sustainable Agriculture, Hyderabad] the small KVM team since 2005, has established active contact with about 3,000 farmers who have attended workshops or subscribed to the KVM magazine. All of them now grow organic vegetables at least for their own consumption. All have stopped carpet spraying pesticides, though a vastly minimised, selective use may still be on. Fertiliser use is falling [-so much so, that traders filed a futile petition in the court to restrain KVM!]. About 300 farmers have converted part of their holdings to organic farming. 500 more are planning to convert. About 100 farmers have gone wholly organic. Exhibitions, seminars and workshops continue. There is a rising demand for their publications which carry instructional articles. Umendra Dutt is full of optimism: "But do go and find out for yourself," he says.

The visit to Amarjit Sharma  of Chaina village was to be a homage to a pioneer, who was the earliest convert to natural farming, whose success attracted worldwide attention and inspired many to make the change. But he had recently been bereaved. He sat sad-eyed and very silent. Handsome Punjabi faces in heavier sadness sat around him, heads bowed. "Amarjit is the single person around whom the fightback was built," says Umendra. "He is sage counsel, active worker and manager of a busy seed bank." Farmers from miles around milled about the front gate, to grieve for the much loved teacher. Amarjit's story and his importance is well told here.

of Chaina village was to be a homage to a pioneer, who was the earliest convert to natural farming, whose success attracted worldwide attention and inspired many to make the change. But he had recently been bereaved. He sat sad-eyed and very silent. Handsome Punjabi faces in heavier sadness sat around him, heads bowed. "Amarjit is the single person around whom the fightback was built," says Umendra. "He is sage counsel, active worker and manager of a busy seed bank." Farmers from miles around milled about the front gate, to grieve for the much loved teacher. Amarjit's story and his importance is well told here.

We are now driving across flat, vast country on fine roads. Canals criss-cross our path. And then very frequently we pass modern sheds with blue roofs and side cladding. They are Reverse Osmosis drinking water plants. A more damning admission of shame and failure by the government and society of a land blessed with rivers is harder to find. And worse, they are mere tokens. A villager would sooner die of thirst or cancer than reach these rare, far and few mechanical oases.

The meeting in Kareerwali village is upbeat however. We sit in the silent, clean yard of the village Gurdwara. It's a meeting of some of Amanjot's flock. They have begun to grow vegetables for the family. They reminisce about old recipes. They talk of their grandparents who lived productive and fit, well into their nineties. Punjab's village streets are a series of tall, wide doors, always shut. But once you push past them and enter the invariably large courtyard you have entered the Punjabi's large warm heart itself. There is the mandatory tree with a rope-cot underneath. A couple of buffaloes are chomping fresh stalks. A tractor stands in a corner. A lady is manufacturing and piling up rotis on an open wood fire. Cattle dung buns have been patted onto hip-high rain shedding cones, where they dry and drop off. Their food is organic. It is only outside their gated yard that they spray and poison the fields; but alas, it penetrates their fortresses riding on the water they drink. But awareness is rising. They slap their foreheads in self-mockery. Change is afoot.

flock. They have begun to grow vegetables for the family. They reminisce about old recipes. They talk of their grandparents who lived productive and fit, well into their nineties. Punjab's village streets are a series of tall, wide doors, always shut. But once you push past them and enter the invariably large courtyard you have entered the Punjabi's large warm heart itself. There is the mandatory tree with a rope-cot underneath. A couple of buffaloes are chomping fresh stalks. A tractor stands in a corner. A lady is manufacturing and piling up rotis on an open wood fire. Cattle dung buns have been patted onto hip-high rain shedding cones, where they dry and drop off. Their food is organic. It is only outside their gated yard that they spray and poison the fields; but alas, it penetrates their fortresses riding on the water they drink. But awareness is rising. They slap their foreheads in self-mockery. Change is afoot.

Jaganmohan Singh of Kauni is nearly 7 feet tall and a journalist's nightmare: he barely talks or meets your eye. One can sense a quiet rage in him. The interpreter says he is angry with the seed and chemical companies -and the state as colluder- in enslaving India again. His family owns 38 acres and resists his passion for natural farming. Over the past 6 years he has converted 4 acres. He grows barley, pulses and wheat. It takes a little more labour but there is labour available in the village. He uses far less water, expenses are low and selling prices are high. The wheat is sold before it's unloaded in his yard. He gets thrice the market price for wheat and twice, for pulses. "With the stranglehold of the MNCs and our industry on the government and the farmers, do you really expect things will ever change?"

of Kauni is nearly 7 feet tall and a journalist's nightmare: he barely talks or meets your eye. One can sense a quiet rage in him. The interpreter says he is angry with the seed and chemical companies -and the state as colluder- in enslaving India again. His family owns 38 acres and resists his passion for natural farming. Over the past 6 years he has converted 4 acres. He grows barley, pulses and wheat. It takes a little more labour but there is labour available in the village. He uses far less water, expenses are low and selling prices are high. The wheat is sold before it's unloaded in his yard. He gets thrice the market price for wheat and twice, for pulses. "With the stranglehold of the MNCs and our industry on the government and the farmers, do you really expect things will ever change?"

For the first time he looks directly in the eye and hisses softly: "India's freedom didn't come easily, did it?" ["Azaadi tho asaan se nahin ayah, hai na?"]

If Jaganmohan is angry,

He went on a tour of India searching for a lost culture. In Rajasthan he discovered large scale natural farming, practiced by Krishna Kumar Jakhar. He saw wheat, mustard, barley, grams, fodder and cotton grown there. He realised from the working farm, that culture dictates and follows natural farming. Since 2002, he began to convert. Today, his entire 24 acres is organic. He met Umendra in 2003 during a campaign against Bt Cotton and has been the President of KVM. He believes the fightback is on. "Without spirituality, there can be no farming," he has concluded.

Charanjit Singh Punni, 46

The story of 61 year old Swaran Singh of Karmgarh Satran is best told in his own words. It is a good story to carry away from Umendra Dutt's world and to remember it by.

"Thank you. I am glad you liked the meal. Everything you ate was grown by me: the wheat, the pulses, vegetables, the oil and the spices. Maybe salt was bought in.

"4 of my six acres are leased out; I manage the other two. I have no help but I personally work the two acres fully. I never learnt to drive a tractor or a motorcycle. My bicycle serves me well. I am off at 5 every morning. The farm is three kilometres away. My breakfast comes there at about eight and I work till 1. I get physically ill if I miss my farm work.

"I have stopped attending family weddings. I attended my children's though; couldn't have missed them, could I? My daughter is married to a taxi driver in Singapore and my son works out of Mumbai on ships. They have been asking me to visit but no way I am going anywhere.

"Amarjit Sharma of Chaina is my guru. He talked me out of chemical farming. I was hooked by Subhash Palekar in a workshop arranged by Umendra's KVM. That was in 2005. Today I am a successful, happy farmer. I make a net of Rs.35,000 a year out of my two acres after feeding our family of eight and four buffaloes. We have almost no cash expenses.

"Let me tell you what I produce from my two acres in an year; note them down. 15 quintals of wheat, 50 quintals of fodder, 30 litres of mustard oil, 600kg of vegetables, 40 kg of garlic and onions, 30 kg of pulses, 8 quintals of cotton and 4 litres of milk per day.

"I carry everything on my bicycle. I take the manure and seeds to the fields and bring back produce. Canal water flows by and I use our borewell very rarely. I am a self taught homeopath; I minister to people and cattle.

"My two acres await me every morning. The soil is crawling with earthworms and birds are buzzing them all day. I lie under a tree for some time every day to take it all in. Wish I could take you to see. You wouldn't want to leave. Lots of people come seeking information. I have gained a lot of respect in the community."

Swaran Singh pauses, as though to clinch his case. "Do you know," he adds, a glare fixing me. "when my bicycle needs repairs, the mechanic refuses to charge me?"

How can you beat that life?

______________

Kheti Virasat Mission

Post Box #1

Jaitu-151202, Faridkot, Punjab

Phones:+91 1635 503415, +91 9872682161

email:

Website: http://www.khetivirasatmission.org/

...

June 2012