Rural folks' cancer deaths are less talked about than their suicides, but the scale and causes are the same.Since 1997 Dr Debal Deb has been conserving 700 varieties of native rice that seed companies are trying to drive outAnshu Gupta's volunteers driven Goonj, collects, sorts and distributes clothes for the poorFor over a 100 years Olcott Memorial High School in Chennai has been giving free education to the poor.

Birds and animals, share with man an equal anxiety for food and shelter. They hunt and gather and build nests or lairs. But it is clothes that give us our distinct human identity. We titter at naked people. We may not on a street, be able to distinguish hungry or homeless ones, but an unclothed one? Why, that'd unnerve us.

Everyone somehow scrounges a garment or at least a rag to claim human-hood. Since naked people are a rare sight, problems of clothing are not readily apparent to us.

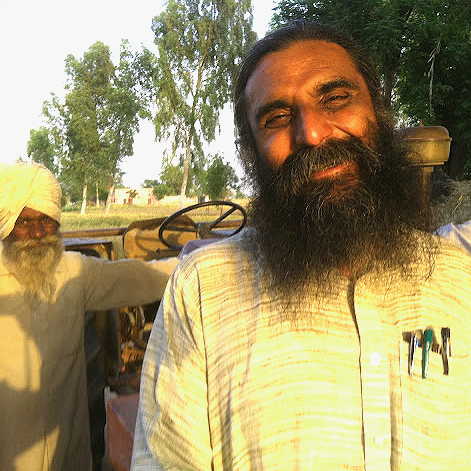

They were not apparent to Anshu Gupta either- not for a long time. But when the point went home eight years ago, it did with a vehemence that he has not quite recovered from yet. He is a man obsessed with the issue of clothing and our ways with it, our ignorance of it. Today he has a large and growing movement. You can participate in it with little cost of time and money and make a huge difference, in giving fellow Indians some dignity.

Fighting it out, finding a place:

Influences on him came over several years. First was the stock he comes from. Anshu was born in Meerut in 1970, to Shiva Das Gupta, a civilian employee of the armed forces and his wife who was the daughter of a post office employee. They had three children and money was always short. But idealism wasn't lacking. Anshu's grandfather had a small business, which he gave up to follow Gandhi.

Neither did they lack grit. At work, Shiva Das had been framed and sent home, pending an enquiry. It took him an year but he fought back to clear his name and get his job back. "But that one year was enough to get into a debt trap that took us 15 years to come out of", says Anshu. "Most people don't have any idea how families without steady incomes, cope to keep their body and dignity together." He saw his father come through, walking upright. Anshu was ten.

In another seven years, he was himself to add to his father's woes. Multiple fractures sustained in a road accident kept him in a hospital for an year. The army's medical aid did not extend to its civilian employees so the family had more bills to pay. Father had no resentment of the fresh debts piling up; he was melancholy because doctors feared Anshu may not walk again.

"I will be a writer," he reassured his father. His first piece in Hindi was published in Sapthahik Hindustan, even as he lay recuperating. Impressed, father made several sorties to the Indian Institute of Mass Communications [IIMC] to get his son admitted. [By the way, Anshu has since walked tens of kilometres in the hills].

Though it sits on several hundred acres of woodland within Chennai, the Theosophical Society [TS] maintains a low profile. Few people know what theosophy is or what goes on in the vast campus. To its north is the Adyar Creek and on the eastern side, the Bay of Bengal. Towards the south sprawl the vast acres left to nature. Old classical buildings dot the grounds, and silence reigns. Environmentalists are delighted that there is this corner of Chennai that is beyond the pale of development vandals.

For that reason alone it is best not to draw attention to the TS. But its leadership by a quiet and gracious old lady, Radha Burnier, is difficult to ignore. She lives and works almost alone in the century old bungalow that Madame Helena Petrovna Blavatsky lived in. Blavatsky and Henry Steel Olcott founded the TS in 1875. But of direct interest to us here, is the unique free school started by Olcott in 1894, for which Burnier still finds the money and time.

For the forgotten people:

Nineteenth century was possibly India's greatest reformist era; and there was much to reform. British Rule had been seen through for what it was, and nationalist aspirations were rising. Simultaneously, flaws in Indian society were being looked at anew. Ram Mohun Roy, Vivekananda, Aurobindo are some of the many Indian names that come readily to mind from that period.

But there were also several non-Indians, drawn to the east by India. Of them, Henry Steel Olcott, an American, is one of the more extraordinary. In legendary American fashion he was many things rolled into one; he had been a farmer, teacher, soldier, lawyer, writer and of course co-founder of TS.

"Olcott was an educator," says Radha Burnier. "When he looked around, he found the caste-less Indians excluded from all considerations. There may have been mutual barriers among the four castes but they at least had their own spaces in society. Those that were called Panchamas, or 'fifth class', had none whatever. Mission schools did accept them, but what Olcott dreamed of was a service without a religious agenda."

In 1894, in a charming little building that still stands, the first of Olcott's Panchama Free Schools opened its doors to children of toiling, ignored people of Chennai.

"Oh, Jaipur foot!" you exclaim. "I know all about it."

Well, what do you know? That the artificial foot was invented in 1968 in Jaipur by a traditional craftsman? That the orthopaedic surgeon Dr P K Sethi, who brought it to the world's attention, got the Ramon Magsaysay Award in 1981?

Both true, but there's more to the story. Master craftsman Pandit Ram Chandra Sharma got no share of the prize money nor enough of the credit. Dr Sethi went away with the prize to consult for a commercial hospital fitting prosthesis. Between 1968 and 1975, only 50 or so limbs were fitted.

Yet, since 1975, over 300,000 limbs have been fitted. Another 600,000 beneficiaries have received calipers, crutches or tricycles. All given away free. India became the world leader in practical, low-cost foot prosthesis. And the Jaipur foot has become available throughout India and 18 other countries.

How did all this come about, if the invention crawled for 7 years after it won world acclaim? For that you have to meet the self-effacing Mehta brothers. That's the real story of Jaipur Foot's success.

Revived by a crash:

How Pandit Ram Chandra Sharma came to develop the Jaipur foot has been well told. He had been invited in the 1960s, by Dr Sethi to teach art as therapy to polio victims at the SMS Hospital. 'Masterji' as he is widely known, is however a restless man prone to looking around for problems to solve or things to make. He watched amputees being fitted with impractical, expensive, imported artificial limbs.

Ever the experimenter, Masterji created a foot made of vulcanised rubber hinged to a wooden limb; and the Jaipur foot was born. It has been continually innovated ever since with active involvement of Masterji. Its essence has however remained: ease and speed of fabrication, lightness in weight, low cost and suitability for working people in the Third World. Though the innovation attracted world-wide appreciation and gave Dr Sethi the Prize, it largely remained an object of adoration and failed to reach the thousands in need of it.

That process that took the foot to the people, was triggered by a crash. In 1969, a promising young IAS officer, Devendra Raj Mehta, was battered in a road accident in Jaisalmer, Rajasthan. It left him with over 40 fractures and many months in bed. It nearly wrecked an illustrious future that was to include Deputy Governorship of the Reserve Bank of India, Director Generalship of Foreign Trade and Chairmanship of Securities and Exchange Board of India [SEBI].

After his long stay in bed ended, he was advised physiotherapy at the Sawai Man Singh [SMS] Hospital in Jaipur. The Jaipur foot had recently been invented and he saw poor, maimed people throng the hospital in search of it. They lived on the streets and waited their turn for a fitment. Mehta during his several visits, was struck by the huge number that was in need of prosthesis.

Dr G G Parikh, aged 82, sits ram-rod straight in the front seat of the Sumo as it moves fairly swiftly through Mumbai. It's the Republic Day, 2006 and streets are free. Mangla Behn, his wife sits with a gentle smile in the back seat. She is about two years younger than him. They are headed for Panvel from Grant Road, where they live. It's a 2 hour long haul even on holidays; they have done the 90 km weekly run for 35 years with rare exceptions.

Just past Panvel, the car slows down at Tara, an Adivasi village. A few women stand at the edge of a dusty road, in their formal best, with platters of flowers, kumkum, lit oil lamps and an arati for the Parikhs. A brass band of school children strikes up. A spindly-legged marching platoon of boys escorts the car slowly, through the bedecked, wet-eyed village to a 3 acre clearing. Here suddenly is a generously laid out school. It is one of Dr Parikh's realised dreams. There is a large gathering to honour G.G. - as he is fondly addressed- and Mangla Behn.

G.G. doesn't show his emotions; his are the only dry eyes. The man is determined and seems set to deliver his message at the meeting. From the conversation during the ride, it is clear it will ring with a passion that is said to belong only in the young. He half turns and whispers: "You see, forty years ago JP wanted to do something for Yusuf".

Then he walks slowly but firmly, using a stick, through the silently admiring crowd towards the dais.

The 'Socialist' tag:

Yusuf Meherally Merchant, to give the full name, was born in a wealthy Gujarati family in 1903. But he had no stomach for business. In fact disowning mercantilism, he dropped his surname. He trained as a lawyer but could not enrol as an advocate because of his record of agitation against the British.

Yusuf Meherally was a sensitive man and an aesthete. He bewitched and befriended everyone he met. His passion for the humanist ideal made people swarm around him. He was a frail man who kept bad health, but that did not abate his fire. He was of the crop of young men that dreamed of a just India after the British left. 'Communism' was a banned label then and so 'socialism' —for which there was then no working model— became a flag of convenience.

Acharya Narendra Deva, Achyut Patwardhan, Ashok Mehta, Prof Dantwala, Jaya Prakash Narayan [JP], Sane Guruji, Minoo Masani, N G Goray, R M Lohia and of course, Yusuf Meherally were the early socialists. To some of them, it was an economic idea, to some a reformist one, to others a violent revolution and to all, a passionate commitment to India. Most of them did not marry. They were driven, talented men, with a firm eye on the egalitarian India they wished to realise, but Gandhi kept emphasising on the importance of the means to that end.

It is strange to hear Alka Zadgaonkar say, "Plastics are useful to our lives. We can't deny that."

Were she a spokeswomen for the dishonest, self-serving plastic industry lobby, that statement would be understandable. Were she a legislator we could say she was evading the issue. Her statement will likely infuriate many of us agonising over the plastic litter all around us.

But hold your breath. Alka loves plastics for an exciting reason; she is the inventor of a process that has the potential to clear our environment of plastic waste, create a million jobs in waste management, add useful, profitable products to our economy and make India a technology leader in taming plastics. Her work is breathtaking good news for this planet's environment.

Pie on the table:

We are not talking of a pie in the sky idea that is still in the laboratory. Alka and her husband Umesh, are buying in 5 tonnes of plastic waste everyday in Nagpur at prices attractive to rag pickers. They are wringing fuel oil out of that unsightly pile and selling it to industries in the Butibori Industrial Estate, on Wardha Road out of Nagpur. Production from their plant, Unique Plastic Waste Management & Research Co Pvt Ltd is sold out for the next year.

They are making money right now, and are about to scale up and buy in 25 tonnes of plastic waste a day. That production too is booked. As Nagpur generates only 35 TPD of plastic waste, they will shortly run out of raw material to grow bigger. So, a plant based on their technology may soon be playing in your town, at a factory near you.

All your questions:

Too good to be true? Let us at once address some of the questions that are already popping up in your mind. Zadgaonkar's is not a demo plant running on some government grant or subsidy. They took a commercial loan from the State Bank of India in 2005 and have already begun paying back. In fact, the government let them down and Zadgaonkars decided to flex the great Indian entrepreneurial muscle. [On that, more later.]

The process invented and patented by Alka Zadgaonkar is capable of accepting all tribes and castes of plastic waste as input: carry bags, broken buckets and chairs, PVC pipes, CDs, computer keyboards and other eWaste, the horrible, aluminized crinkly bags of the kind that pack crisps, expanded polystyrene [the abominable 'thermocole'], PET bottles- are these and others are all given equal opportunity to contribute to Zadgaonkars' profits. No sorting or picking is done.

No preparatory cleaning is necessary either, except shredding that helps economic transport of bulky waste. All solids and metal fines settle down in the melting process or are converted to ash.

Chlorinated plastics like PVC are particularly hazardous to burn because they emit dioxins. In the Alka Zadgaonkar process, the entire shredded mixture is melted at a low temperature and led to a de-gasification stage. Here chlorine is led away to harmlessly bubble through water, producing hydrochlorous acid.

Among the prestigious Indian Institutes of Management that were commissioned in the 1960s, the one at Ahmedabad [IIMA] has always been perceived to be the most exclusive. Perhaps its paternity [the Harvard Business School], its charismatic founder [Dr Vikram Sarabhai], its dazzling architecture [Louis Khan's] and the rigour of its admission process combined to gain IIMA that reputation.

For four decades now, its graduates have been plucked off by great business corporations in India and abroad at salaries princes might envy. Surely personalities that go through the institution must have grit and brilliance. Surely too, they must be originals. Otherwise, every now and then, a graduate of IIMA would not do the unconventional.

Like M P Vasimalai, who evaded all campus recruiters in 1983 and opted for an opening to help manage the lands donated to the Bhoodhan movement founded by Acharya Vinobha Bhave.

Another era, just 50 years ago:

The story of how Vasi [pronounced 'Vaasi'] as he is referred to by everybody, came to mould the DHAN Foundation can wait till later. Let us just note for now, that DHAN currently has 400 professionals working in 6,000 villages of 6 states in India, trying to revive rural economies. A survey of the times he grew up in, will help to lead us to the DHAN story.

When he was born in 1956, he was named after Vasimalayan [pron. 'Vaasi-malayaan'], the presiding deity of his village, Ezhumalai near Madurai in Tamil Nadu. Those times -a mere half a century ago- are eye opening. True, child mortality was high. Just five of his parents' ten children survived. But on the other hand, their extended family of 20 people could support themselves, and prosper on just 8 acres of land by natural, accustomed labour. Vasi's father presided over the large brood; he was stern, reserved and assertive but also took total responsibility.

He physically laboured well into his seventies. He had seven sisters who lived with their husbands in the house. The husbands worked as labourers for others to plough land, harvest crops, build houses,ferry produce to market and so on. They were frugal men, incurring minimal boarding expense in the large house; and they were gone in a few years, having bought small parcels of land from their savings. There were cattle and carts to care for, sheep and chicken to raise, and grains, vegetables, fruits and oil seeds to harvest. Oh, yes they were sturdy men of the soil.

The land was generous too. Water was available in the village's numerous wells at barely ten feet depth. They irrigated and farmed with animal power and produced plenty. Going to school was no excuse for not working. Vasi had to feed the animals before school and go directly to the fields after it. Once he had turned in his contribution with muscle, he was left alone to play with his mates or read the hundreds of Tamil books from the school library.

Then the times changed.

On the morning of September 4, 2004, a bailiff from the Sub-Ordinate Court in Chengalpattu arrived in Karikkattu Kuppam, a fishing village in the Muttukkadu panchayat, that lies along Chennai's tackily modern East Coast Road [ECR]. He asked to be shown the house of Mr Arumuga Chettiar. Chettiar is the 70 year old headman of the Kuppam. As a small group gone tense by the sight of a Court's emissary followed him, the bailiff strode with importance through the narrow streets.

A fat envelope was formally served on the Chettiar. The unlettered man who can barely read Tamil, stared at all the papers that spilled out, almost entirely in English. The Ameena [-as a bailiff is known in colloquial Tamil] explained that the Court had issued an interim injunction against him and his men from entering the temple lands in the village on an appeal to the Court by MGM Beach Resorts, a commercial establishment nearby. The case against him was to begin in three weeks.

Their first instinct was to rush to the MGM management seeking help and relief. They were used to unexplained, unfair targeting. After a brief discussion however, their second instinct took hold. A delegation of them rang my door bell. I went through the served papers and was stunned. I pointed out that this was MGM's ruse to intimidate them and to instil fear. They could either succumb to that or fight back. They chose the latter.

An aside

In the five and a half years that I have been publishing GoodNewsIndia, I have remained invisible, believing the author's name is irrelevant to the content of a story.

This story, the 100th in the Magazine section, breaks that convention. Here was an issue in my own back yard that bristled with nearly all the ills that beset India today: environmental vandalism, land grab, suppression of community rights in the name of tourism, unauthorised development, noise pollution, groundwater abuse, misuse of police services, intimidation of powerless people and most despicably, trivialisation of the legal process. The people I have been writing about in these pages all these years, have stood up against these very ills and made a difference to the course of public life.

Were I to stand aside to the MGM Group's power play in a village that has been my home for 25 years, I'd have no credibility left to live my life with, let alone continue publishing GoodNewsIndia. So I became a part of the story, now being narrated unavoidably in the first person.

Apologies also for the length of the story and the many details in it. This is because this piece is intended to be authentic documentation.

- D V Sridharan, Publisher, GoodNewsIndia

Every morning this was the question from their three small children, resentful at being left alone for another long spell of 14 hours: "Where are you going?" The parents, Mary Vattamattam and Choitresh Kumar Ganguly ["Bablu"] found it equally hard to leave—or, truthfully name the places their work took them to. The children wouldn't have coped with names like Chennakothapalli, Mushtikovila or Shyapuram. So they took to saying: "We are off to Timbaktu!"

It had already been a long journey for the two of them to this point in the late eighties. And their goal, however they imagined it, was still afar as the metaphorical Timbaktu.

Adventures of Mary and Bablu are of interest not only because of their current work with nature. Their story is of value to understand, how during the dark eighties when the State lorded over everything, small Indians nevertheless stood up for their convictions and struggled on layers beyond our eyeshot. Mary and Bablu were part of the flux agitating for a fair deal for rural India. They began with Marx, and had doubts rise in their minds. When the took to caring for land and trying to grow food, they discovered the relevance of Gandhi. Utopia however is still very far, but now, the road feels right.

Players in flux

By the sixties, it was clear India was sleep-walking through its Independence. It was not sure of its identity, ideology, politics, economics or statecraft. Every voice and idea was fighting for space. Poverty, shortages and insecurity stalked the land. Sincere people, all wanting a better India, had each, a prescription.

The colonial mind set had not changed. [Many believe it still hasn't]. Bablu tells an amusing story: "My father was an agitator for India's freedom and was thrown in the jail by the British. After Independence his application to join the police force was rejected because he had a 'jail record'. Ironies didn't stop there: my father went on to England to qualify himself for a job in India".

Bablu's childhood through the sixties was in Bombay and Bangalore. He took to the theatre rather than to academics. When he was 20, he met the legendary Narendar Bedi of Calcutta.

Here's an example of how the meek might inherit India. Here too, is an insight into what really makes India tick, keeping hope alive amidst unrelieved chaos and selfishness. A small bunch of office clerks, typists and receptionists in Mumbai have found themselves a mission. During working hours they were viewed as rulers of ossified interiors of government offices. After work, they seemed to have no relevance.

A chance offered itself 15 years ago to shrug off their ghost like existence in the big city. They grabbed it to become people who matter, instead of people seen —if at all— as hurdles. Every year they visit the Konkan coast bearing goods and support for hundreds of schools. The rest of the year, they work to plan for that visit.

They are babus transformed into guardian angels of Ratnagiri's poor school-children. They run the Lanja Rajapur Sanghameshwar Taluka Utkarsha Mandal - 'Association for Uplift of Lanja, Rajapur and Sangameshwar Counties'.

How green -and grim- the valley:

A vast district in southern Maharashtra, Ratnagiri is for the most part green and pretty. But despite abundant annual rains, its intrinsically agricultural community faces an unobvious sort of poverty due to recurrent droughts.

Education though esteemed, is elusive. Majority of schools are located many miles away from scattered homes, past steep hillocks and streams that overflow in the rains; it's a daily trek that many children make without shoes, umbrellas or school uniforms.

Nearly none of the schools has furniture; classes are held on the floor with as many as five different grades handled simultaneously by a single teacher in one classroom. And for this service, there are fees to pay; though modest, they are still beyond the means of most parents. Thus it is, that it's hard to keep children in the 1500 or so schools of Ratnagiri's talukas. Most students drop out of school by class 7 or 8, to become farm hands or industrial apprentices in nearby towns.

For a democracy to amount to more than a mere ceremony of elections, it must have dynamic media, courts and laws. India has a reasonable set of these. But that's not enough. A democracy further needs leaders who will marshall these resources to serve people. For over a decade, pioneers like Aruna Roy in Rajasthan and Anna Hazare in Maharashtra have striven for just that, after zeroing in on denial of information as democracy's most crippling disease.

Lack of transparency creates the musty environment in which vermin of oppression thrive. Due largely to the efforts of Roy and Hazare, India has begun to evolve Right to Information [RTI] laws.

Even that is not enough. What a maturing democracy needs are ordinary people who believe they have the power to make laws stick; people like Arvind Kejriwal and his team at Parivartan in Delhi.

Development puzzle:

Arvind excitedly protests the focus on him. "I am but one of my team," he says. True, but since we must begin from somewhere, his life is good place to do that.

Nothing in his background foretells what he has become. He was born in Hissar in Haryana in 1968 and knew no deprivation at all, as his father was a well employed engineer. Arvind went to the prestigious IIT, Kharagpur and graduating in 1989, joined Tata Steel. Within 3 years however, he was a restless man.

"While at IIT I noticed government service was an option many students considered," he says."I won't say we were all driven by great social concerns, but deep inside was the vague feeling that one can make a difference from within the government."

E F Schumacher overhearing an expert declare "Technology is the answer", famously asked, "What was the question?". That retort is appropriate for the current times when many of India's leading minds are advocating linking of our rivers.

If the question was about water shortages, the answer probably lies in local solutions, micro successes, raising awareness, involving people and altering collective behaviour. The attempt to engineer river linking would be a tragic folly were it not an undoable feat. For a fraction of the money that the State will waste chasing that chimera and fail, citizens and groups are attempting simple, common-sense solutions in water gathering and succeeding.

Little drops of water, says the hackneyed verse, make a mighty ocean;likewise, these small efforts will aggregate to a grand solution someday. And deliver a slap on behalf of Schumacher.

Tamil Nadu leads:

If ever water conservation becomes an urban citizens' movement in India the state of Tamil Nadu will have triggered it. For a long time, builders had been required to put in roof-top rain water harvesting systems [RWH] in new constructions. But recoiling under two years of drought, the government in July 2003 got pro-active: it proclaimed an Ordinance that gave three months for all city buildings to retro-fit RWH systems. Most commendably, all government building had to fall in line as well. Widest publicity was given across the state. Civil servants were asked to make RWH their number one priority. School children marched through most streets urging citizens to act. There was also a stick: if a building missed the October deadline, it's services were liable to be cut and have RWH systems installed by the state, with costs to owners. Things began to happen in quick time.

In 1967, 25 year old Bindeshwar Pathak had missed getting a First Class that would have landed him a lecturer's job in a college. He tried being a school-teacher, a pay-roll clerk and even a street by street salesman of his grandfather's bottles of proprietary home-cure mixture.

Deciding to get himself a Master's degree at Sagar University, MP, he boarded a train. At Hajipur, an elderly family friend talked him out of his move and promised him a 'good job' instead, in the Gandhi Centenary Committee at 'Rs.600 per mensum'. He got off the train and was led to Patna. The promised job wasn't quite there nor did life settle down for him, but he believes that his lifelong commitment to scavenger liberation through maintenance-free toilets began that day.

Contrasting Grandpas:

Or had it? Maybe it in fact began when he was a child and growing up in Vaishali and Sitamarhi. Maternal grandfather Pandit Jaya Nandan Jha had been to jail in the cause of India's freedom, even before Gandhi did in India. He had in fact been Gandhi's pilot to Hajipur and Vaishali. Pt. Jha was an egalitarian. The paternal grandfather was the opposite, though.

"Time spent at the Pathak household were mystifying," says Bindeshwar. "Of the many 'rules', the one about not touching certain people intrigued me. Grandmother would sprinkle water on the paths such people had walked. And mutter some, as she did."

One day, young Bindeshwar decided -as children are wont to- to 'touch' a classified woman, just to see what happened- and hell certainly broke loose. He was given a ritual bath and administered a nugget of cow-dung and cow-urine, chased down by water from the Ganga.

When finally Damodar 'Damu' Acharya rebelled in 1980 and set out to organise oppressed fellow workers, little did he know what awaited him. It took him quite a while to ask what he now says should have been obvious: "Why are there children amidst adult workers at factory-gate meetings?"

World of the working child is barely visible to most of us. We have developed a blind spot. There are a quarter billion child labourers worldwide, including the US and Australia. India contributes a handsome share to that number. These productive labourers have few rights, let alone spells of innocence and childhood.

Damu did ask the question soon enough, and from that moment has grown an endeavour that has raised awareness about the plight of labouring children, led to the passing of legislation to protect them and is today, a worldwide movement that enables children to assert themselves in the life around them. Their sorrow continues yes, but at least now, we hear their sobs.

Discovery walk:

Damu was born in 1957 in Basroor, Karnataka. Son of a poor temple priest, he dreamed of educating himself to land a stable job. He left his coastal town for Bangalore and gained his college degree in 1978. Then began the hunt for a job. He lived by himself paying his way as a caterer, construction supervisor and as a odd jobs man. Then came what he thought was a big break. Macmillan the publisher, was starting a photo type setting unit.

D Acharya B A, applied and was selected, trained for 3 months and was confirmed as a permanent employee. Damu thought he had arrived. What a brand to work for, he marvelled! But his long walk had just begun. His shift began at 6 am. So he awoke at 3 am to walk several kilometres to be on time. At work they sat in a line like oarsmen in a galley. Their time out to the wash room was logged. They were not allowed to talk to each other. Just as well because 8 hours were barely enough to complete the work load. Their college degrees were docked with the employer. All this for a salary of Rs.200 per month.

Within a year Damu began to organise fellow workers. He was thrown out without his certificate being returned to him. And that crisis brought him to Nandana Reddy.

He runs no NGO, has built no check dams nor leads any community development. Among GoodNewsIndia's little known heroes, he is even less known, unknown even except in the neighbourhood of Mori Road, Mahim, Mumbai. He is 84.

Devkishan Lakhiani is portrayed here because he can be a role model for many of us who say we'd do something for India, soon as we have saved enough or our children are settled or our career has stabilised or we have retired or whatever else. Lakhiani -affectionately, 'Dada' to everyone- shows you can do something right now. He runs a free homeopathy clinic, and until a few years ago taught at the nearby school and offered legal counsel to the poor. He has done that 'something' throughout his life.

He is a man of few words and has no complaints or grouses or advise. He's busy the whole day. His is a perfect world.

Bomb maker's apprentice:

Dada was raised in Karachi in a large family of six boys. His father was a rice processor. He probably went through some casual schooling and worked for the family business.

When about 25, he found himself in the company of Master Jethanand, who believed in scaring the British out of India with bombs. Deeply nationalistic, young Devkishan became his acolyte. It is doubtful if they were serious arsonists. "We did not intend killing anyone; just terrorise them," says Dada. With such a fuzzy agenda in mind, the motley group flung a bomb, not at, but in front of a British building in Pinjrapara. They then ran in all directions. Dada was not as fleet as the Master and so was caught and imprisoned for three and a half years.

When he came out, the British were preparing to leave India, least of all due to any violence they feared from the Master or Dada. But the Lakhiani family faced true violence in Karachi. An extended family of 20 moved to Mumbai, then Bombay.

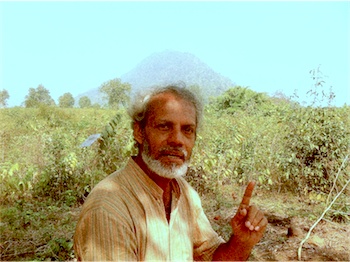

It is March,2004. We are driving from Dharwad to Surshettikoppa. Off the highway, it's a blistering landscape. On a powdery earth, trees are holding their places with forlorn dignity. Vast brown spaces between them are in startled silence. A line of racing monkeys break the scene. Amidst them, a mother with a baby slung under.

Dr Prakash Bhat is brooding. "Four years of drought. Free animals have been hit hard. They are under great stress. Man has been lucky enough to survive."

Everywhere in the south of India, droughts and debts are leading to suicides. But in about 25 square kilometres around Surshettikoppa, farmers have learned to stare back at droughts, survive and in rural Indian terms, even prosper.

Has magic been wrought here, or is it lunacy at work elsewhere in India? Dr.Bhat— and BAIF, his employer— are propagating nothing more than common-sense solutions gained from soil level work. In under six years, Dr Bhat with staff of ten, has freed 10,000 people from fear and privation. These people are not afraid of droughts anymore.

"Going away" as a way of life

We are going to observe the transformation of nearly 2,500 families in 22 villages in Kalaghatagi and Hubli talukas of Karnataka. Till the year 2000, having between 2 and 5 acres of land meant nothing to them. In a good year rainfall would be close to 1000mm but very often, around 500mm. They could not live off their land. It was common for men to go away to industrial nodes at Noolvi, Hospet and Yellapur and slave at dehumanising porterage labour in mines and at rail heads. Villages often consisted of only children and women. Children 10 years old, were sent away as cattle-grazers to other towns under the 'Jeetha' system, which fed them for work.

BAIF, a love child of Dr Manibhai Desai, has had a presence in Dharwad since 1980. Dr Bhat, a veterinarian recruited by Dr Desai, was an early arrival. BAIF had been at work improving livestock quality. The poverty everywhere was striking.

The road north, out of Udupi induces peace and calm. The Arabian Sea to the left, the sense of space and the bright light make you wonder if there can be anything better.

Soon you learn that there is. Turn right at Brahmavar ['Gift of Brahma'!] and right again. You are on a road fast asleep. Trees stand tall, broad and quiet. Fruit lies on the ground unclaimed. There are so few people about. You have just dropped through two or three floors of time, from noisy, crowded India.

10 km down the road at the village of Cherkady, 86 year old Ramachandra Rao welcomes you with a pitcher of water and three tiny cones of jaggery, into his 2.5 acre homestead. He's a small, wiry man with twinkling eyes on an untroubled face.

He is eager to tell his story and it is best we have it in his voice.

Gandhi is all you need:

"Sir, I was born in Kodagu [Coorg] in 1917. When I was two, my father and mother, died mysteriously within a day of each other. My older sisters had been married. I was first brought to one of them in Dharmasthala and then here to Cherkady where another sister had been married. My brother-in-law was a farmer some distance away from here. I grew up grazing his cows and helping out in the fields.

"They sent me to the local school when I was close to 10 and I spent just two years there. That has been the only formal education I have ever received. Or needed.

"My teacher Ramachandra Patil had only one subject: Gandhi. He spoke of his life, thoughts and courage. He spoke of Gandhi's frugality, devotion to nature and self-reliance. He spoke of nothing but Gandhi the whole time, and we were all under a constant spell.

"Patil-Teacher even kept a charkha in the school and we all fought each other to learn to spin. My two years were soon over. The farm needed my labours. I am glad I studied no more, for that would have diluted what I learnt.

"I was growing up in the fields helping my sister's family. In my spare time, I was spinning the charkha at home. In my late teens, deciding that I must have a career, I went to Brahmavar to learn weaving. I made my first money when I was 22, for fabrics I had woven. I had not known money until then.

Weaving wins a bride:

"I gained a reputation as a good weaver. Oh, I loved it: the smell of lint in the air, the clack of the loom and the film of sweat on my skin. The whole thing was very meditative and kept me fit and well-fed. It gained me my wife as well. Her father thought me a stable fellow and she too began to weave. We earned Rs.600 per year as weavers. Life was good.

This mid-summer 2004, it is introspection time in India. The recent general elections, have triggered many streams of debate. Every stake-holder has an interpretation of convenience.

Of the many subjects that are up in the air now, the economy is the one most glibly commented upon. In the space of just three months, the public mood has gone from sanguinity to doubt. The 'public mood' in India, one must hasten to explain, radiates from just about 100 million or so Indians—not necessarily,the well-to-do— who are given to opinions. However slight their weightage in the poll process, they do actively affect the political process that follows a poll. Their minds—happily— are open to facts and logic. It is worth addressing them for they influence the choices India makes.

No more fuzz:

India in the 21st century, is a different place. Several sections of the society—hitherto sullen— have seen change and improvement. Others—even as they remain outside the loop— are witnesses to those changes. No longer is India, a hopeless nation. Charismatic sloganeers may have thriven in bleaker times. Today's Indians ponder the public life. And the economy has a huge share of their minds. Within it, concerns are of unevenness or lack of access to the prosperity pie. Not of, despair.

So, India is assessing solutions that will enfold more citizens. Must it reverse or slow the modernisation process, undertaken in the last decade? Or whether the economy should be broadened and deepened. Should the economy be muscular or cuddly. Can it be both? The time has come for everyone to make a choice regarding a development model suited for India. The era of ambivalence is over.

More so, in the light of China Shining. News from there has always swayed Indians. In their eyes China has been shining for a long time. When an Indian tourist comes back from China in awe of its visible prosperity, it matters little to the overall mood. Indian businessmen's enduring admiration for China's ways can be explained away by their impatience with procedures in India. Left leaning politicians and commentators wear their loyalty on their sleeves and their views can therefore be annotated.

But when the London Guardian headlines an article [by Jonathan Watts], "World applause for Beijing's record achievement in creating and spreading wealth", it's time to sit up. There are more amazing statements to contend with.

Annie Besant of the Theosophical Society proclaimed in 1920, that Jiddu Krishnamurthy, a young man of Madanapalle in Andhra Pradesh was an emerging spiritual leader of the world— a Prophet, even. JK as he popularly came to be known, was far too wise to be trapped in the robes of a Messiah. He soon broke loose, and began a life that made him a world renowned teacher. But this story is not about his life. In 1925, JK had motored through villages beyond Madanapalle. He came upon a splendid banyan tree and stopped right there. Here he would found a centre of learning. He did that, and it is today the Rishi Valley School. This story is not about this school either.

Dominating Rishi Valley where the banyan stands even today, is the Rishi Konda or Hill of the Rishis. Legend has it that rishis had lived up its slopes in grand isolation. Folk memory even recalls that a line of flaming torches could be seen up there on some nights as rishis and their students made from one cave to another.

Somehow, that legend of rishis, and the metaphor that a banyan stands for, have a relevance to the story we are about to tell. Ours is the story of this valley's modern day rishis. Rishis of yore lived for the success of this planet. So too, do the people we will meet in this story. They are promoting conservation, restoration and adoration of nature. They are not rishis however, living in isolation, as did the ancients; they are spreading—banyan-like, close to the ground— and reaching out to simple folks, giving them education, health and hope. Their work—like the vines'— shows how committed people can bring about harmony in the extended communities around them.

Two starts in the seventies:

Although the Rishi Valley School dates itself back to 1932, it was not until the 1970s that it entered a mature phase and began to resemble what it is today. For the first forty years it was more a series of experiments under several teachers rather than a system of teaching with an identity all its own.

In many ways, those directionless years are akin to the years of drought that can occur in this valley. The 1910 Gazetteer noted that the Rayalaseema region in which Madanapalle and Rishi Valley belong, was "rich in natural springs". The nearby Horsely Hills were thickly wooded, where elephants and bears had roamed. Yet by the thirties, the valley was a barren, rocky moonscape, thanks largely to pressures of railway building, population growth and profits in timber. It therefore became routine for this man-ravaged land to have several years of drought followed by a year or two of rainfall.

Goa enjoys a prosperity greater than the rest of India. Its standard of living would rival that of Asian tigers. On human development criteria too, it would score well. Goans are a spirited, hospitable, fair minded, God-fearing people. While 26% of all Indians are in poverty, the figure for Goa is less than 10%. Its roads, beaches, resorts and open-ness would make you believe you were in the south of Europe.

But beneath the cheer, problems gather and lie like the garbage that affluence generates -- for someone else to clear. The most affected are the children. Several thousands are growing up without knowing childhood. Even while battling on their behalf using familiar means, Bernadette D'Souza and Gregory D'Costa are working on a deeper plane. Beyond laws, they believe is a God-given right of all humans to realise their full potential. Their organisation Jan Ugahi, means 'Self realisation for all'.

The story of how they came to this mission is fascinating; one that is so very Indian. Greg used to be a priest and Bernie, a telephone operator.

Mines and beaches:

Under Portuguese rule for over 400 years, Goa had developed a unique culture all its own, with a very Latin flavour. In 1962, Goa hit world headlines as a 'sovereign state' 'annexed' by 'imperialist India'. When West's moral outrage subsided, its people began to come over -- in curiosity first, and for the infectious friendliness thereafter. The Goan had charmed them.

The Portuguese had also incubated many native entrepreneurs who went by names like Chowgule, Dempo, Salgaokar and so on. Many of these were known worldwide as mine and ship owners. The Persian Gulf job-boom that began in the mid seventies made even the middle and lower layers of Goan society cash rich. There was much spare money looking for investment opportunities.

Goa decided to invent itself as a tourism destination. The construction boom of the 1980s, --combined with labour shortages, due to many Goans away in the Gulf-- drew poor migrants from drought hit areas over the hills, notably Bijapur in Karnataka. They built the now shining Goa and manned its many menial services. Even as Goa became world's darling, immigrant labour and tourist influx were precipitating new social problems. Housing shortages, slum living, denial of civic rights are a commonplace. Slum children are also victims in the now notorious Goan crisis: paedophilia.

Plastics arouse passions. The technos say plastics are omnipotent; that man's future will be fully served by its miracles. The greens say, plastics have no merits whatsoever and must be un-invented. Amidst slogans of "ban plastics" and "use plastics with care", the debate rages. Keeping a low public profile, petrochemical plants keep loading sacks of plastic granules on to an endless line of trucks. The people --you, me, the rich, the poor, the savvy and the innocent are using and throwing away plastic. The most committed amongst us are startled from time to time to learn how, despite our best efforts, plastic has crept into our lives. Damage done by plastic litter is getting deeper and more widespread; we have everywhere, the surreal slow-burn of piles.

It comes as a relief therefore, that there are creative realists at work, tackling the issue without passion. GoodNewsIndia has highlighted some of their work over the years. But the work we are about to review, is on an entirely different plane-- it has the potential to end the debate and turn the problem into an opportunity-- particularly for India. GoodNewsIndia therefore makes an exception to its publishing policy and features an idea rather than a realised project; that too, an idea of a non-Indian. It does so in the great hope that this article will motivate tens of concerned Indians to bring the idea to this country. With that preface, GoodNewsIndia introduces the little-known, pioneering work of James W Garthe, a Professional Engineer at the Pennsylvania State University, USA.

Which cycle?:

Industry says that plastics can be recycled. Environmentalists disagree-- they say plastics can only be 'down-cycled' in the sense, it can be converted to a lower-grade plastic product. What then is the fact? Fact is, plastics are extracted from petro-chemicals and the most that can be done is salvage as much of the calorific value as possible out of used plastic. That is the closest possible approximation to what is known as 're-cycling'. If well done, the only objection we could have to this approach, is the one we already have against the use of petro-fuels.

In a way, nature is even handed: about 3% of all children --across countries, races, religions and cultures-- are 'special'. They arrive on Earth with their unique gifts but mainstream life has little time for them and considers them a problem. While physical debilities become reasonably obvious, identifying those that we have learnt to call 'special', is a task strewn with many barriers. No clinical tests exist to diagnose different mental builds. Over time, these differences need to be 'inferred'. A few among them, like those with Down's syndrome [--or mental retardation] are easier to pick. When it comes to autism however, diagnosis gets complex, because autism spans a wide spectrum: from the barely discernible to the well-defined, with several shades in between. For a long time, these special children in India were denied their special needs because of adult ignorance, social taboos, parental embarrassment and lack of 'specialists'. In the last 3 decades however, India has mobilised itself in its own ponderous, incremental way to address the requirements of these special citizens.

India's response to autism, is a saga of individual endeavour with little support from the state. In terms of care and concern, this peoples' activism has served society's needs, in ways that will rival those of wealthier countries. We survey the scene through the work of a small service in Bangalore called Shristi Special Academy.

Mothers' guts:

Not surprisingly, it is the mother who first senses if her child is unusual. No, she doesn't at once accept the fact and call her child 'special'. That comes later. She first goes through the gamut of self-pity, denial, embarrassment, prayer and despair. And then comes the realisation that she had a problem that won't go away. Action follows.

Most of the action that governs the autism scene in India today, seems to have begun around 30 years ago. In Hubli, Mrs. Vaishali Gore realised in 1975, that her son was mentally retarded. She trained herself to care for him, and began training other parents from 1982. Mrs. Merry Barua in Delhi in 1982, came to serve the cause of parents of special children, because she too had a special child. In Bangalore several parents came together in 1978 to form the Karnataka Parents' Association for mentally retarded Citizens. [KPAMRC].

Let's face it: for all the many things we Indians can be justly proud, we do suffer from an incompetence when it comes to sanitation. Some would even judge us a vicious society. After all, have we not for centuries expected a whole caste of fellow Indians to clean up after us? How little we train our children in toilet use. How terrible our public --and frequently, even private-- toilets are. How shoddily we design, build and maintain them. Gandhi, wise as he was to Indians' ways, chastised us and urged us to clean our own latrines. Alas, to little avail. The best groomed Indian often leaves a wrecked toilet behind. It is not surprising that we are a laughing stock around the world in this regard. Truth is, we have an uncomfortable, unprocessed mind mess when it comes to toilets and our responsibility towards them. Now at last we have an Indian, who is aware of this problem; who is proud of creating and maintaining sparkling public toilets. If Fuad Lokhandwala is emulated widely, there is hope yet, that we will correct a gross flaw in our collective outlook.

A Jay Leno jibe:

The year was 1998. India had thumped its chest and declared itself nuclear. Indians brimmed with pride. The world reacted with anger, threats and sanctions. All that flew over the heads of gleeful Indians. Fuad too was euphoric-- but he stopped dead in his tracks one day, while watching a Jay Leno Show on TV. The burly wit had said something to the effect, "Indians can build nuke bombs but they can't build decent toilets." It hurt. And yet, as with the best of humour, how true!

Fuad was in his forties and had spent 25 years of his life in the USA, as a student and as a professional. "I loved it there -- the energy, the systems, the order. I longed for India to be up near there someday," he says. "It puzzled me as to what we lacked. What was it that we must get right?" Back in India he had not quite settled down to life in Delhi. He was unsure as to what he should be doing. A routine 'job' made no sense.

What he didn't quite know about himself was that he was a Yankee style entrepreneur. Jay Leno uncorked that. Fuad's obsession began that moment: "I will build world class public toilets!" It is obvious that such a resolve would invite ridicule in India. His loving wife Mehru and daughter Sanaa were 'deeply concerned'! But an obsession must run its course.

Not 'pay', but 'paying' toilets:

After six months of trying to sell his 'crazy' vision, Fuad had the ears of K J Alphonse, an activist bureaucrat. Alphonse was apprehensive but nevertheless took him to 'his minister', Jag Mohan. Fuad had their attention. Yes, it was time we built toilets we need not be ashamed of, but how would we fund them. It was one thing to get New Delhi Municipal Corporation [NDMC] or Delhi Development Authority [DDA] to permit him to build his dream toilets, but where would the money come from for maintenance and as return on investment? After all, you can't load on the user all that it costs to build and run.

Sell clay, and you are selling a commodity. Make it into a pot and you have manufactured a product. But if in the end, you send a designer bowl to the markets, then you have a brand and all the big ticket profits. It has taken it a while, but there is growing evidence that India has internalised this simple reality. This is the secret of success in world markets: create true value first and then create an illusion of even greater value. India's legendary knowledge edge and its skilled, industrious workers are right now updating the act that said it all first: the Indian rope trick.

Up from copra:

When the British left in 1947, they left India with a mindset that it wasn't fit for anything more than exporting jute, copra, tea, spices and cashew nut. 'You stay with commodities and leave manufacturing to the industrialised nations,' seemed to be the message. Quite unwittingly, India's central planners' response of *making* India into a giant, seemed to confirm just that: Indians were not there yet. The one debate that won't die is how Fabian socialism delayed India's date with its genius. Do skip the debate. That date is at hand.

When economic reforms began in the nineties, it had largely to do with dismantling domestic controls. There was no need to clear the way to the world markets: it lay open. Some captains of industry feared hordes coming through the open doors;after all, they had been beneficiaries of a closed-door India. But the doughty neo-Indian entrepreneur saw the open door as an exit leading to the world beyond. In just over ten years he has changed India's economy and its image.

It is best to savour the changes by surveying the current scene. And it is best to begin the survey with jute, that so epitomised India. Today jute is making a style statement. It is no longer used as just sacking material. Indian application research has made it a candidate in the list of interior and accessory designers worldwide. On another front jute is being promoted as a geotextile, a class of material that is used in huge quantities in civil engineering works. Khadi is not far behind either, in its climb up the value chain. It is not a politician's badge any more. [In fact the pols wear less of it these days; is there a profound meaning in that trend?]. Khadi is haute couture. Today, the word itself is a brand that evokes and enhances India. Earlier this year, a media report quoted Giorgio Armani: "The khadi made in India is among the most skin-friendly fabrics we know. In fact the day isn't far when khadi-based designs will rule the world." The Gandhi inspired Sarvodaya Ashram, Delhi supplies fine, vegetable dyed khadi to Gucci, Donna Karan and Armani.

Anuradha Goburdhun Bakhshi says she is paying back a debt to India. But that is strange accounting. She hardly owes anything to this land -- unless you count her lineage. Her great grandfather shipped out to Mauritius from Bihar over a century ago as an indentured labourer. By the time she was born in Prague the family had prospered. Her father Sri Ram Goburdhun -- a judge--, had heeded a call by Pandit Nehru, taken Indian citizenship and become a diplomat. Anuradha --an Ambassador's daughter-- was raised in the lap of luxury in world capitals. She spoke French before she spoke Hindi or English. Life was a lark with cruises, parties, fine dining and savouring of classics. Marriage to a rising executive meant postings abroad again. As the French translator to Indira and Rajiv Gandhis and with connections in high places her life seemed to drift closer to the clouds.

Yet today, she spends her waking hours in Delhi's Giri Nagar slums, battles to raise money for her adopted brood of 500 young people and rides a three wheeler to the courts, to donors, to reach Page-3 people and anyone who might further the cause of her wards. Anuradha's story reveals the way India weaves her magic over those that display the slightest affection for her.

Asking 'why?':

Her sense of indebtedness to India is perhaps inevitable given her forbears. Goverdhan Singh --labourer No.354495-- who shipped out to Mauritius in 1871 on S S Nimrod never forgot his village Barka Koppa, District Patna. He returned to take a bride --and dig a well for his village. Anuradha's maternal stream in the meanwhile, was outspokenly nationalist. Her grandfather Gopinath Sinha a freedom fighter, made jail going a commonplace. Her mother to be -- Kamala--, had sworn she would not marry in an enslaved India. When India did become free, Kamala was 30 and a Red Cross truck driver running errands to mitigate the rigours of one of India's many famines that the British had neither the inclination nor the wit to prevent. In 1948, Ram Goburdhan -- a barrister at law from the Inner Temple and a licentiate from the University of Lille-- took Indian citizenship and began a career as new India's envoy.

Anuradha says her father's distance from India gave him a romantic outlook and her mother's more recent experience of it made her a sturdy realist. Even as they exposed their only child to the rationalism and fine arts of the West, they laced her life with an Indian-ness. It was an influence she was unaware of through a rebellious teens and effortless successes in academics: upon her parents' insistence she qualified for the IAS and having proved to them her ability, refused to join it. Marriage, two children and a glamorous career as interpreter followed. Then, quite quickly between 1990 and 92 both her parents died.

To many, Sanskrit is a dead language. Some think it's a 'useless' language. Quite a few Hindus preen themselves that it is exclusively theirs. But did you know serious scholars are beginning to marvel at the rigour, reach and secularism of Sanskrit? Many of these --all over the world-- are mining it for values the modern world can benefit by. But nearly no one does this exposition with greater commitment, catholicity and religious neutrality than Prof M A Lakshmi Thathachar at the Academy of Sanskrit Research, Melkote, Karnataka. On the 15 acres of the Academy, the assertions in Sanskrit texts regarding ecology, farming, health and right living are on view. The Professor is a farmer, livestock breeder, conservationist, researcher, teacher, computer adept and most of all, a man who embodies all that is best in the Indian tradition. He is a Renaissance man unique to India.

An ancient seat:

Melkote [pronounced 'May-l-kottay'] claims a connection with Sanskrit since the mythical times when Saint Dattatreya is said to have taught his disciples the 'true knowledge'. More certainly, history confirms a connection at least since the 12th Century when Sr Ramanujar, scholar, social reformer, father of the bhakti movement and founder of Vishistadvaita philosophy made Melkote his home. One of his devotees -- Ananthalvan -- is a direct ancestor of Lakshmi Thathachar. Their family, has been custodians of Sanskritic heritage ever since. One of the country's oldest, formal Sanskrit college was formed in Melkote in early nineteen century.

Young Lakshmi Thathachar was a robust young man, farming the acre behind his house. He produced all the vegetables and fruits for the family. He tended the household cattle. He had a scientific bent of mind too and wanted to study science in college. But his father forbade him 'sciences'. It was feared he would be distracted by the western way of thought and miss the self-contained scientific system in Sanskrit. Thathachar -- now 68 -- feels his father was right. He worked for his Masters in Sanskrit at Madras university. While at it, he was also a pupil at a small gurukulam run by the great Sanskrit scholar, Sri Karappankadu Venkatachariar. The learned man was ageing and repeatedly urged Thathachar to build a centre that will bring the works of Sri Ramanujar to the world. That message was to remain with him throughout his career in Bangalore University as Professor of Sanskrit.

In nearer history, Melkote had been ruled by a dynasty founded by Yaduraya. His clan had built several water retaining structures --kalyanis-- of great effectiveness and beauty. A small scholarly community had thriven there. In early 19th century, Tipu Sultan's army descended on a Deepavali day and massacred 800 citizens, mostly of a sect known as Mandyam Iyengars. Sanskrit scholarship had been their forte. [To this day Melkote does not celebrate Deepavali]. That slaughter rendered Melkote a near ghost town. Its environmentally connected life was broken, kalyanis went to ruin, water shortage became endemic, the hills went brown. Sanskrit lost a home.

While check-dams have been the heroes of watershed development programmes everywhere, allocating a small area in each farm for a storage pond is truer to the spirit of rain water harvesting, namely 'catch the rain where it falls'. Check-dams are invariably down-river, down-in-the-valley structures where land is already quite productive and comparatively well served with water. Check-dams located there, trap the water which in fact fell on the higher catchment areas where the poor are. It is always the upper reaches in undulating terrains that are harder to farm and therefore left to the marginal people. In an effort to reverse and correct this inequity, BAIF Institute for Rural Development, Karnataka [BIRD-K] persuaded over 300 slope farmers to build small ponds. And that changed the water economy of a 700 hectare area in Hassan district in Karnataka. Don't be surprised, though. Wherever the long arm of Mr. Manibhai Desai reaches, efficiency, thoroughness and success invariably follow.

BAIF comes to Tiptur:

By 1980, the redoubtable Desai had arrived in Karnataka and formed BIRD-K. Its mission? Same as ever: 'show rural Indians, ways to sustainable incomes'. BAIF believes that for every local geography there is an integrated solution that is possible, sustainable and profitable. The mandate to its various centres is to find the one best suited to its location.

Tiptur in Hassan district was the entry point selected by Desai for Karnataka-- and with good reason. It is a drought prone area given to erratic rainfall that averages 500 to 700 mm annually. The topography is undulating, varying between 50 and 100 feet. At the lower levels, coconut is about the only crop. In the early days of tube well madness that swept the country, Tiptur too joined in. Rich farmers felt that all they needed was the money to drill a well and let in a pump. Ecological ignorance is a great leveller. The rich soon joined their humbler brethren up hill. Tube wells everywhere ran dry, the water table having gone down to 500 feet. People had lost their way, forgotten ancient, gentle practices and compounded their own problems. [Read about Idkidu, another village that went through --and recovered from-- the bore well disease in the boxed story at this link]

In 1984 Dr G N S Reddy arrived in Tiptur. He had graduated as a veterinarian and drawn by the Desai magic, had joined tens of his classmates to work for the BAIF mission. Quite early Reddy was struck by the tokenism of Government watershed programmes. It was a one-size-fits-all approach with check-dams, bunds and gully plugs etc reduced to a list of numbers. The programmes had no impact on water scarcity, soil run off, deepening of bore wells or migration of even the landed for jobs in the cities.

Amidst all this grimness, were the centuries old 'kalyanis', the dug out, stone lined ponds. There were quite a few of them in the area. They drained the last in the summer; often they survived the summer with some water left in them. They provided a clue. In Gujarat, BAIF had successfully pioneered the 'wadi' development model where small holders were led to sustained incomes by combining fruit trees with grain and vegetable farming on marginal lands, using little water. Why not combine the two at Tiptur?

In 2001 when GoodNewsIndia reported on the work of Prof. Udipi Shrinivasa and his organisation SuTRA, at the Indian Institute of Science, Bangalore, he had already proven the idea of using straight vegetable oils [SVO] as diesel engine fuels. He had demonstrated over a 40 square kilometer area that SVO can deliver power to homes and farms. How was this promise going to be taken to an India out there, we had wondered. The Professor however, had no doubts: "It will happen, Sir," he had said softly. He is a man who knows his India. Two years on, he is proving right. Several layers below the one that main media operates at and reports to you, is an India that is solving problems, bettering lives, adding value. It is the layer at which people are left to their own devices. They have no lobby, not much money,no choices like emigration, but they have no readiness to surrender either. They have their commitment to this land. And --believe it or not-- they have several civil servants at this layer who are helpful in nature, eager to innovate, and therefore willing to back promising ideas. It is from here that the SVO genie will rise and pierce the layers above it. The Professor will then be a media darling. The media --poor thing-- will have much to catch up with and report on.

Tribal energy:

It is instructive to learn how these nether layers function. Let us follow this story: Joint Forest Management [JFM] had been in trial mode since 1994 in Andhra Pradesh [AP]. Its novelty was to co-opt forests' natural people -- the tribals -- as guards rather than treat them as intruders. If they were allowed to sustainably forage the forests for their livelihood, they might be persuaded to zealously guard it. They and not the forest officers would then manage the forests. The World Bank was funding JFM and the programme in AP was headed by Mr. S D Mukherjee, who had pioneered the idea in Bengal. GoodNewsIndia had featured this experiment in April,2002.

The story of Aavishkaar is a fine example of sophisticated paying back by educated, affluent Indians spread all over the world. They realise it was India's knowledge-edge that leveraged them to good lives and so they have sought to widen that edge, by funding small town Indians whose innovations can increase productivities and wealth in the countryside. Aavishkaar itself is a notable innovation. It pioneers the idea of barefoot venture capitalism, so to speak. It bets on the Indian mind. Its experience so far has been that it's a safe bet.

An IIM caucus:

At the Indian Institute of Management at Ahmedabad [IIM-A] , Prof. Anil Gupta pioneered the idea of mining rural India for marketable innovations. He identified the knowledge and skills with India's poor as an untapped resource, thus unlocking a huge treasure which everyone suspected existed but no one had bothered to pursue. His work resulted in a vast and growing database of simpleton inventors. [You can read the full story of his work here]

Early 2000, when Prof. Gupta was visiting Singapore a few IIM-A alumnus met him informally. And the talk veered around to how difficult it was for the small innovator --often little educated-- to find patrons. Gupta's Honeybee network had identified many commercial opportunities. And his GIAN was labouring away trying to connect investors with entrepreneurs. Present at the meeting were Dr. V Anantha Nageswaran, Prof Mukul Asher, and Meenu and Arvind Singh. Out of that meeting was born Friends of Sristi in Singapore [FoSS]. It would be a micro venture capital [MVC] firm! A novel concept for India.

MVC is a cousin to micro-credit, but a bold and different variant. Micro credit movement in India is a runaway success. Several million Indians --almost entirely women-- have been benefited by the availability of small, low cost loans to earn micro incomes. But the lenders and borrowers are members of small groups. They are risk averse. FoSS on the other hand, would bring the rigour of modern management to evaluate ideas and then risk investing in them. The business model that fueled the growth of high tech industries was about to be down-sized and right-sized to meet the needs of an entirely different sort of entrepreneur: one rich in ideas but with few skills to develop them for the market. FoSS was entering virgin territory and hoped to learn and grow as it went.

In a nation where collective finger pointing at politicians, grieving at the slowness of democracy and deriding India itself are fashionable, Rangaswamy Elango is an object lesson. He is an engineer for whom the outer world lay open. He chose to return to his village. He was born a Dalit, a people who have many justified grievances with Indian society. He chose to harmonise passions. He had choices enough to stay away from the rough and tumble of politics, as most educated Indians are wont to. He chose it as the means to lead his village, Kuthambakkam to prosperity. He can spend his life basking in the successes he has wrought so far in Kuthambakkam. But he has chosen to evangelise village centred development. He is a family man with longings for his loved ones. But he lives a solitary life for his cause, Gram Swaraj [--the Autonomous Village]. Most of all, at a time when it is the vogue to belittle Gandhi, he adores the great man as the one who truly understood India. The career path of Rangaswamy Elango needs to be widely known. Just fifty more Panchayat leaders like him across India are enough as nodes from where sensible village development can radiate in all directions.

Well to do but ill at ease:

Elango was born on Nov 12,1960 in Kuthambakkam where his family has lived for close to a thousand years at least. They cherish the association an ancestor of theirs had with the great reformer philosopher Sri Ramanujar, who was born in Sriperumbudur, nearby. Despite being Dalit they have not felt alienated from mainstream Indian thought. Village realities of ghettoised living however, had seemed inevitable. Elango's family owned some lands and his father was a Government employee. So they were reasonably well to do, but young Elango grew up amidst squalor and hopelessness in the Harijan 'colony'. Drunken brawls, wife beating and wails of women and children were nightly fares in houses around his. An academically inclined Elango could not quite shut these out nor ignore the filth and the bogs as he picked his way to his school. His mind however filed these away.

"At lunch I saw my mates had nothing to eat," he recalls. "They would gulp glasses of water and pretend they were alright. I always shared my lunch box. But, there was never enough not did it seem a solution." His mind filed that away too. Walking back from school on hot days, through upper caste streets he found people were willing give him water but not to his mates. Was it because they knew he came from a sober family, was well washed and studious? His mind did some sums with this and the filed information and came to a rough conclusion at an early age. Later as he grew up, he redid those sums and realised what it added up to: there can be no individual happiness if there is misery all around.

At about 80 km towards Ahmednagar from Pune, turn left at Wadegaon. Ask anyone the way to Ralegan Siddhi. They will point you to a Shangri La. Be ready to strain your credulity as facts are reeled off, and evidence is presented. No one starves here --in fact everyone is well nourished--, there's no disease, the environment is clean and wooded, all the young are at school, the farm economy is booming, there are no social divisions, women are empowered and no one wastes time or money on movies, tobacco or liquor.

All this was wrung out of a drought prone 4 sq km land where till 1975, only 80 of its 2200 arable acres were farmed. The annual rain -- about 400 mm in a good year but mostly a third of that -- ran off the undulating land. The 2000 strong population sat and stared at a hopeless future. Children died early, men beat their wives, disease ran rampant and about the only businesses that made any money were the liquor stills - 40 of them. From there to paradise might seem an impossible hop. Yet, all it took was a mere 20 years -- and, an ex-army truck driver called Kissan Baburao 'Anna' Hazare.

Flower boy goes to the army:

Hazares owned 5 acres which if productive, should easily support a family in India. But given the conditions, they were in deep poverty. Young Hazare left for Mumbai after 7 years of schooling. He was in his mid-teens. He began to sell flowers and was quite successful, but life seemed so empty. He would frequent the movies, hang out with mates at street corners and was generally lost. By chance, he came to read the lives of Vivekananda and Gandhi. And gained two firm convictions. From the first, that the purpose of life was to serve others and from the second, never to preach what you did not practice.

China's incursion into India in 1962, provoked him to join the army. He was trained as a truck driver and sent to the front. There, after an accident he was alone and lost for several days. He faced death and when eventually rescued, convinced himself that he had been spared for a purpose. He foreswore marriage and determined to help his village.

Here is the story of a school and a college which rose from the dust.

In 1938, a school was running in a little shanty room with a total strength of 11 boys, one teacher and bank balance of Rs.11. The salary of the teacher was only Rs.12 per month; but the school was on the verge of closing down. Then the miracle happens! A postman takes over its management and by 1944, the school has a fund of a few hundred rupees. The school is well-established with students four-fold and more class rooms. In 1946, the postman's 'Deewali baksheesh' of Rs.4500 and funds collected by staging a play brings the total to Rs.12,000. And the postman and his wards go from strength to strength. Let us view this drama as it unfolded.

A corporal from World War I:

Way back in 1938, the Hindi School at Ghatkopar was one of the only two of their kind in Bombay [now Mumbai]. It was in doldrums when a young postman Nandkishor Singh Thakur, pledged to give his spare time to the school. Well, if Hindi School was an unimportant, unknown school in a suburb of Bombay, Nandkishor himself was an uninfluential person. Born in 1897 in a village in UP, his own education was two years of study in the primary school. But he had seen the world in the first World War - in the Middle East as a Corporal in the Infantry. Five years of stay in Turkey as a part of the British Army had made Nandkishor a changed man.

In 1926, he joined the Post and Telegraphs department as a Postman in Ghatkopar. But his dreams were bigger. He wanted to have a more purposeful existence. And he found an outlet. The combination of this humble, unassuming, simple postman and his little-known one room institution in one of the suburbs of Bombay has now become an epic story to remember.

What is it that drew this short, bald man with a walrus moustache to this school? What was it that made him put [--does so even today] all that he had and 'a little more' to make things better than before? Perhaps, he himself has no answer.

Collection drive:

Hindi School was in a very bad shape when Nandkishor took it over. He didn't know how he was going to add to the bank balance of Rs.11 that was all in the name of the school. But he knew that he had access to all and sundry in that locality as a postman. He made use of his contacts. He carried along with his postbag a small box in which people could drop anything upward from a paisa [1/64th of a rupee]. It was a paltry sum to begin with but the school survived. More than that, people came to know of the school and its humble organiser.

The school received its first large sum in 1946. Nandkishor declared that whatever 'Deewali baksheesh' he would get from the people would be added to the school fund. People gave generously. He collected about Rs.4,500 that way. In a play staged in the same year, another sum of Rs.7,500 was collected, bringing the total to Rs.12,000. The school had come a long way from the days of Rs.11-reserve-fund.

Frequently, when we despair of where India is at the moment we do one of these three things: first we turn on the Government and critique it for all ills, next we decry 'apathetic, lazy Indians' who do nothing for themselves and finally, we propose solutions from elsewhere and moan in exasperation ,"why can't we simply, just, etc....?" Here's a story which will convince you that --uncelebrated by the main media and consequently, you-- whole communities are pro-active, innovative and do not wait for the Government to help them. All they usually need is a sensitive individual to make their dreams come through. Individuals like Girish Bharadwaj.

Lush and locked:

The western Ghats around the border of Karnataka and Kerala are a bewitching sequence of green hills and valleys, balmy sunshine, friendly smiles, ample houses -- and countless rivers. They are of all kinds and variety. The hills soak the rains and create streams, waterfalls, rivulets and whole rivers. They sustain the people --but oftentimes cut them off from mainland life.

There are hundreds of villages in these parts that need to use boats or coracles in their daily lives. To an occasional visitor this is a rather charming way of life. The mind is drawn to imagining how lovely it would be to live here without a care or a stress. You could too, unless you have children you want to send to school or college everyday or commute to a job or care for illnesses or have friends and relatives visit you with ease or wanted stable power and telephones. Around the monsoons the streams swell and cut the villages off. When they are in ebb children and the elderly must wade in the mud to reach the boat. For women it's an indignity to hitch their sarees up to their knees. Frequently, young folk have found it hard to find brides or grooms: 'alliances' in places that may be cut off for months scare Indian families.

The story of how Girish Bharadwaj came to make a difference is interesting. His ancestral village, Arambur, in Aletty district is near Sullia town on the western slopes of Kodagu. But his family had moved long ago. His father was an engineer and Girish was born in Mangalore in 1950. He went to an engineering college in Mandya near Bangalore with only occasional visits to Arambur. Indian engineering curriculum of the seventies was --to put it charitably-- classical. Not much emphasis was laid on experimentation or innovation. You got the sums right and you passed out into a world that hopefully taught you how to apply your basic knowledge.