Rural folks' cancer deaths are less talked about than their suicides, but the scale and causes are the same.Since 1997 Dr Debal Deb has been conserving 700 varieties of native rice that seed companies are trying to drive outAnshu Gupta's volunteers driven Goonj, collects, sorts and distributes clothes for the poorFor over a 100 years Olcott Memorial High School in Chennai has been giving free education to the poor.

Starting the school was easier than running it: trained teachers were unwilling to teach Panchamas. It was a time before Gandhi coined the word Harijan and started the ongoing process of integrating them. So the early teachers were theosophists, who transcend doctrinaire religious sanctions.

Radha's father N Sri Ram was a theosophist who went on to become the President of TS in 1953. She was born in 1923 and grew up in the environs of TS. In her young days, the Panchama Free School had only teachers from abroad. She remembers Miss Sarah Palmer and Miss English and her brother. Olcott had died in 1907. By then the school was in steady-state and had produced an alumnus good enough to become a teacher. He was Ayya Kannu, who served the school for long.

Fast forward to now:

Annie Besant had taken over from Olcott as President. The five Panchama Free Schools in Chennai were consolidated into one at Adyar. Fittingly, it was renamed Olcott Memorial High School [OMHS]. The Olcott Education Society[OES] was formed to integrate many related activities.

A 19th century classic

Henry Steel Olcott was born in 1832 in New Jersey. After education at Columbia University, NY he was a share cropper in his uncles' farm in Ohio. There he discovered his interest in the occult that was to be his life-long driving force. He then studied agriculture formally and started a farm school and wrote extensively on the subject.

Olcott was a daring man as well. When Virginia banned any Northerner from witnessing the hanging of John Brown, he made it incognito and wrote an account of it in a New York paper. He then served in the Civil War and after the war ended studied law. His integrity led to his appointment as investigator of fraud in the US Navy. After Lincoln's assassination, Olcott was appointed to the three man investigating commission.

In 1894 he met Madame H P Blavatsky and it proved to be a seminal event. Mme Blavatsky had been a para normal since a child. She identified her master in a childhood dream, met him [-he was a Rajput.] in Hyde Park when she was 20 and went into Tibet in 1868 and trained for two years under her masters. She and Olcott were drawn to each other. They founded the Theosophical Society in 1875 in New York.

That was not the end of Olcott's talents. He turned out to be a popular healer, converted to Buddhism and established Theosophical Society branches throughout the world.

In such a large man's life, the founding of Panchama Free Schools is but a tiny achievement; but it nevereless underlines his search for fairness, and from there, perfection on earth.

He passed away in Adyar in 1907.

Based on a memoir by Sarah Dougherty

All the foregoing is by way of a foreword. If that were all there is to it, it would be mere history. Instead, OMHS is a living throbbing school. By 1972, the small parcel of land where OMHS had begun, was bursting at its seams. TS moved it to its present premises about a kilometer away, closer to the sea. That's how it has come to be the envy of even schools for the well-to-do.

OMHS sits on a 9 acre campus constantly aired by the sea. It has vast playgrounds, as Annie Besant strongly believed sports to be a great character builder. There are leafy lanes and class-rooms are abuzz with children. 750 in all, 35% of them girls. Teachers are mostly alumni. The medium of instruction is Tamil.

The charming, original school building and campus remain with OES. A Social Welfare Centre operates there under the OES umbrella. There is a training centre for women to earn home based incomes, like tailoring. More importantly, there's a bustling playschool with ample playgrounds, for nearly 200 children. They are between ages 2½ and 5. After that age, OMHS welcomes them and takes them all the way to Class-10.

Prompted by Mahavir:

He recalled that experience later. He was back in service and risen to be Principal Secretary to Chief Minister Hardeo Joshi. 1975 was the 2,500th birth year of Mahavira, the founder of Jainism, which the Indian government wanted all states to celebrate fittingly. Leaping over obvious token gestures, D R Mehta suggested rescuing the Jaipur foot from its neglect and delivering it to the needy.

"Where will we do it?" asked the Chief Minister. "We have no funds for building and stuff." Mehta suggested using ramshackle ambulance garages of SMS Hospital. His proposal was accepted. The Bhagwan Mahaveer Viklang Sahayata Samiti [BMVSS] was born in 1975. Masterji was delighted to be back in active mode.

Technology by itself cannot bring about change, however elegant it may be. The Jaipur foot was no doubt a technical winner but what made it lie unavailable to the needy? There were no processes to manage its delivery in thousands.

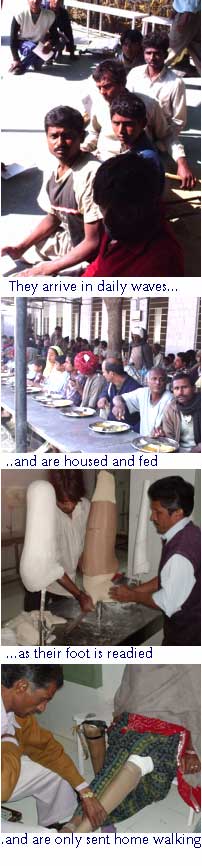

"The first thing I wanted changed was the approach to visitors," says Mehta. "It had to become human". It was common for the maimed to arrive at SMS Hospital and be made to wait for days for mere registration. "These are usually poorest of the poor who lose their limbs in the course of daily labours for employers who took no responsibility. They arrived penniless, starved and were without shelter as they waited for days in hope of being fitted with a limb," he says.

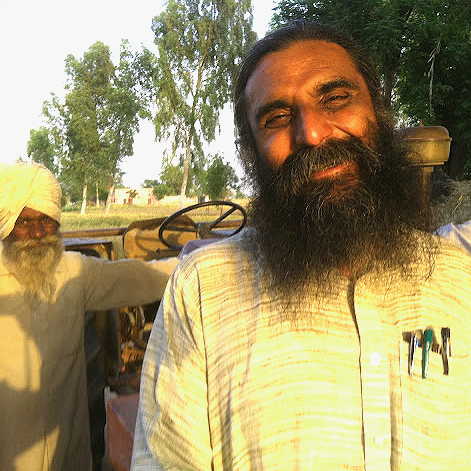

When BMVSS began operations, the first practice he put in place was that registration must be done on arrival, round the clock. Then the patient is given food and a bed. He and a caretaker are hosted till his limb is custom fitted. And she walks out upright in dignity, with return fare in hand. No fees of any kind is ever collected. The whole service is free.

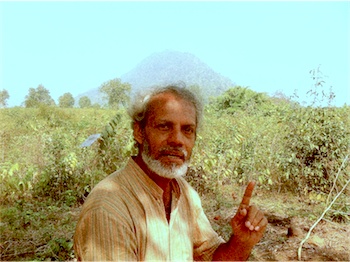

Amputees waiting in wards quicken the craftsmen, many of whom wear the Jaipur foot themselves. There is an ordered assembly line approach to fabrication. Amputee's stump is covered with a knitted sock and a plaster of paris mould is made. From this socket a plug is made which is an exact replica of the limb. High Density Polyethylene Pipe [HDPE] is warmed and stretched over the plug. A vulcanised rubber foot is attached and suitable straps are provided to fasten the limb to the body. Most of the time, fitment is on the same day and comfort with using it is achieved in hours.

Gandhi of course was the lodestar that you could neither resist nor ignore. It is often said Gandhi could make heroes out of fistfuls of clay. But it is also true that strong men were putty in his presence. Or else, how do you explain the fine crop of young men of the 1930s who, seduced by the Bolshevik Revolution, sought it as the key to 'liberate' India and yet could not defy Gandhi's patient, seemingly illogical ways?

A different 'young people':

Today most Indians are not aware of the political activism of young people in the first half of twentieth century. [A recent film 'Rang de Basanti' on the period has astonished unaware Indian youth.] Kisan Mehta's recollections of the times gives some of the flavour: "Chetana Restaurant had by then become a haunt for progressive thinkers and writers. It was a place where Jayaprakash Narayan, Achyut Patwardhan and other socialists met whenever they were in Bombay...Kalbadevi-Bhuleshwar-Hanuman Galli were Meherally's arena for fighting social oppression, injustice and inequality as well as for vanquishing the orthodox within the Congress. Meherally had exhorted me "to live dangerously and to keep hopes high and expectations low" while signing my autograph book." [Read a stirring sketch of Meherally's life at this link]

G.G. heard Meherally speak in 1942 at his college and was at once smitten. He became a Cadet Member of the Socialist Cell in the Congress. Within months his opportunity came to 'live dangerously'. Cadet G G Parikh, a student all of 18 years, was at Gowalia Tank, Bombay on August 8, 1942 to back Gandhi's call to the British to Quit India. He was arrested and slapped into Worli Jail for ten months.

Revolution takes time:

Mangla Behn was born in Sholapur, Maharashtra in 1925. Her father was a Gandhian and Theosophist. He was a progressive man who sent his daughter to Shantiniketan to imbibe Tagore's sensibilities. G.G. continued his active role as a socialist even as he pursued his medical studies. He and Mangla met as fellow activists and eventually married.

But that was later. One gun-shot on Jan 30, 1948 was to change many things. As Gandhi lay dead, the force that he wielded over his followers, weakened. Many went into government and more or less succumbed to the ways of the British Raj. Lohia began his rebellion and took on the Congress. Sane Guruji was so disillusioned at the non-arrival of the just India of his dreams, that he killed himself. Yusuf Meherally wasted away to an untimely death in 1950. JP turned to Vinobha Bhave and his Bhoodan movement. "And there are some today who call themselves 'socialists' " with whom G.G. will not care to exchange a greeting. Socialists had scattered or mutated.

Several years later in 1975, JP was to precisely specify how one were to achieve a 'total revolution' that would create a fair India: "This is not something that can be achieved in a day or in a year or two. In order to achieve this we shall have to carry on a struggle for a long time, and at the same time carry on constructive and creative activities. This double process of struggle and construction is a necessity in order to achieve total revolution."

Process path:

Shredded waste is continually fed into a conventional extruder. Here over the length of a heated extruder screw, the waste is plasticised and melted at a relatively low temperature. The melt is then stripped of chlorine as we just saw, and led to a reactor where lies the crux of the invention. The melt interacts with proprietory catalysts invented by Alka. The stable, continual chain of carbon found in all plastics is destabilised by a depolymerization reaction and rendered ready for a rich harvest.

Three streams of produce are obtained. A part of the gaseous cloud is condensed to form a liquid hydrocarbon. This is the recovered fuel oil. It is a sulphur free equivalent of industrial crude. It can be readily used in furnaces or put through fractional condensation to obtaine finer grades like petrol. For a long while to come, the best market for this is as furnace oil for process heating in factories. Zadgaonkar recovery plants, when they spread in the country, can use plastic from local dumps and serve local industries which currently buy expensive furnace oil from far away.

What is not condensable at the reactor is obtained as a LPG equivalent. A modified genset can generate electricity using this gas. This is now standard practice at a Zadgaonkar plant, which is self sufficient for power. The final remains are a solid fuel called petroleum coke. Approximately 70% is liquid hydrocarbon, 15% is gas and 5% is solid coke. Balance is ash and metal fines.

And now the story:

Alka born in 1962, has always had a fascination for organic chemistry. "I was intrigued by the way new products can be created by playing with carbon and hydrogen molecules," she says. "There was a sense of great control over things." That mind set was to eventually lead her to her invention.

After marriage to Umesh Zadgaonkar, she settled in Nagpur and began teaching chemistry. Umesh is an MBA and a natural entrepreneur- which means he has an ability to grab the opportunity ball and carry it over the line, eluding all tackles. He was the first to bring health clubs and gyms to a sleepy, conservative Nagpur; he realised the idea would appeal to citizens given to living the clean life. In contrast, Alka is a small, self-effacing lady fiercely committed to teaching and housekeeping. Their son Akshay is a computer prodigy.

In 1993, Alka first began to notice plastic piles in their clean and pleasant Nagpur. The menace was already a huge problem in big cities and there was a rising chorus of concern demanding solutions. These ranged from fiats to ban carry bags use [- as though other forms of plastics were innocent], to recycling to making the industry pay. "You can't wish away plastics," says Alka. "They have become a part of our lives."

She began to think of a creative solution. It was still pre-Internet days and she did not have ready to access to the state of the art. She knew her chemistry, though. She began arguing that the source of all plastics is petroleum. The trick is to revert them to their previous life where they become petroleum again. Plastics get their variety and stability from strong continual, patterned bonding of the carbon molecule. If this long chain is disrupted, they would collapse and can be coaxed to their original form. The process of disruption is random depolymerization.

Oh, what a revolution:

In the late 1960s, the Green Revolution arrived in south India's villages. The only external output in farming so far had been some diesel for pumps' engines. Now chemical fertilisers, pesticides and exotic, high yielding seeds were arriving. There were unbelievable bumper crops that called for little effort. The land was worked round the year. The pumps ran non-stop. Everyone was rich overnight. "The memory of my schooldays is of all round boom," says Vasimalai.

Just when everyone thought the party would never end, water in the once perennial wells began to go down. By 1970, drillers were roaring into the village to insert tube wells inside open ones. Submersible pumps were needed to pump water from great depths. Yields dropped, input costs rose, profits vanished. Farmers were getting into debt. By late eighties, in under two decades of the revolution, bankruptcies began. Large land holders became itinerant labourers in towns. Mercifully, Vasi's father had died in 1984, some years just before total bust. They sold their cattle and carts; they gave up on farming.

Disconnections had occurred everywhere: between man and his habitat; seasons and sowing; extraction and replenishment of water and nutrients; in the connection between animals and land; in the culture of saving some grain as seed; in the economics and advantages of collective living in large families; and in the notion of living well off the land instead of running it like some factory.

All this was happening as Vasi was growing up to be a young man. None of the trends were registering on him then, he recalls. "I had seen a boom and a bust; I didn't understand what caused them." He was in the stream of an educational system where only examinations mattered and learning if any, was accidental. And he was a good student, excelling especially in mathematics. He took a bachelors course in agriculture. The whole thing was bookish, looking at agriculture as chemistry and economics of maximization. "In the final year a group of students were given a half acre of land and was asked to produce a crop," says Vasi. "That was it. We passed and swarmed out to manage India's agriculture as bureaucrats, bankers and inputs marketers."

Vasi got into IIMA in almost a fit of absent-mindedness. He had done his masters, served the government briefly and was working as a researcher. A friend mentioned IIMA and its entrance test. "I was tempted because it gave me a reason to visit Madras [now, Chennai] and a temple near there," he laughs. He wrote the Common Admission Test [CAT] and found it numerically biased. Being a math natural, he answered it effortlessly. He then forgot about it.

About a week before his family-arranged marriage to a girl from a nearby village, he learnt of his admission. And that was how, M P Vasimalai, who grew up working the fields, studying in village schools in Tamil, who saw a city -Madurai- briefly when he was ten, arrived, in 1981 at a cutting-edge institution of learning, housed in an awesome Louis Kahn designed campus in Ahmedabad, Gujarat.

South to North to South:

Mr M G Muthu, the patriarch of the MGM Group had by the 1990s grown prosperous with contract work in and around the environs of the docks in north Madras [-now Chennai]. He had come to Chennai from deep south Tamil Nadu with little in his pockets and had risen to be a rich man very quickly; that speaks volumes for his acumen, daring, and hard work.

The Group began to diversify. They arrived in Muttukkadu in 1992 to enter the leisure industry and began to buy property. Muttukkadu, south of Chennai is a far cry from the dirt and grime of the north where they had made their fortune. It was becoming, in the throes of India's economic liberalization, a place to make lifestyle statements like weekend homes, or at a minimum, a space where the nouveau riche stated their values.

Fishermen welcomed MGM as they believed there would be jobs and a market for their catch. MGM was a big ticket spender buying whatever land they could. What they could not buy-like the 1 acre in Survey No.102.E where one of Muttukkadu's many shrines stood, or the village pond north of the highway- they simply added to their fenced in collection. The holdings increased until it stretched from the highway to the sea, albeit with a narrow sea front. In 1993, it stood abutting a temple grove by the sea where 88 yielding coconut trees nodded in peace. This grove was on three wooded acres in Survey Numbers 108/9 and /10. There was a tiny shrine worshipped by fishermen.

I have spent many afternoons 20 years ago in the shady grove, lounging with a book by a sweet water pond there. The Hindu Religious & Charitable Endowments [HR&CE] department, the owner of all temple lands in Tamil Nadu, had an Executive Officer [EO] resident in nearby Tiruvidanthai. He conducted an annual auction for the usufructs rights to the 88 trees. The winning bidder earned the right to harvest coconuts and fallen leaves. He had no rights whatsoever to the land itself. It was a small business for a villager. In 1993, MGM bid and won the rights for a mere sum of Rs.3,500 per annum. Why would a large business house bother with a micro-enterprise? We soon had the answer to our puzzlement.

From Sacred Grove to Party Land:

In 1997, MGM began to implement its master plan. Its fleet of earth moving equipment began to work round the clock disturbing the neighbourhood. Sabita and Navaz, with their young child and elders at home could barely sleep. They began to write to the management complaining of noise. By 1998, the fishermen woke up. They found access for worship in the grove barred by MGM's security force. Worse followed. MGM began felling yielding coconut trees in the grove. A few fishermen stood in front of bull-dozers that were busy scooping off beach sand and uprooting coconut trees in the grove. Police would materialise within minutes to keep peace for MGM. Police began to chase fishermen away if they as much as walked on the beach in front of the resort.

Narendar had been affected by his work with Vincent Ferrer, a Spanish Jesuit priest living in India since 1920. In the late seventies Ferrer, seeing the poverty all around, ended his life as a man of cloth, married an Englishwoman and went around rural Maharashtra observing farmers in distress. He became the centre of a huge media controversy. His programme of drilling tube-wells for farmers was suspected to be a Trojan horse. Forming Rural Development Trust [RDT] to continue his work with creating irrigation facilities, Ferrer moved to Anantapur, Andhra Pradesh.

Narendar was living in the USA with his wife and two sons when he read of Ferrer and his work in the LIFE magazine. He came back to India to work in the rural areas on the invitation of Ferrer.

Anantapur, scorched by the sun:

Anantapur district in Andhra Pradesh is located in the Rayalaseema region. It is perennially drought prone. It receives the second lowest rainfall in India: 522mm. Of its 4 million population, close to half were deep in debt. Only 15% of its cultivable land is irrigated. It challenges men of action. And they came.

Green Past [-from timbaktu.org]

Today Anantapur District is nearly a desert, however this was not always the case. Anantapur District was part of one of the most powerful and rich kingdoms of south India - The Vijayanagara Kingdom. Penukonda, situated 70 kilometers south of Anantapur town and 140 kilometers north of Bangalore Metropolis, was the summer capital of King Krishnadevaraya, some 500 years ago.

In the late 19th century a well known British forester had described the forests of Penukonda as one of the finest summer deciduous forests in the south. The Pomegranates and Sitaphal of Penukonda were well known even in the courts of Delhi. For over 700 years, from the Vijayanagara Rayalus to the Bahamani Kings, from Tipu Sultan and the Nizam of Hyderabad to the British, great armies had fought to keep control of this rich and fertile land.

Although the rainfall was always scanty, the farmers knew how to deal with this situation and their agricultural techniques suited the conditions. They had an appropriate selection of sturdy drought resistant crops and their cropping pattern protected the fertility of the soil, which they further increased through on farm production of manure. An elaborate system of scarce water resource management by harvesting of rainwater through tanks and canals allowed successful farming under difficult conditions. Effective community management insured the fair use of the Commons and the sustainable use of natural resources.

Teak and Hardwikia Binata, two of the finest timber trees to grow in India, were exported from here to lay the railway line between Gudur and Madras. Till recently, food and fruit crops in the district were grown with rain water harvested in more than 300 major irrigation tanks (Cheruvu), some having Ayacuts of over 1000 acres and known to store enough water to grow two if not three crops a year. There also were numerous minor Tanks (Kunta) and perennial springs. Many different local varieties of rice, major and minor millets were grown here.

After a few years with Ferrer, Bedi decided to start the Young India Project. Capt Davinson, associated with MYRADA [Mysore Resettlement and Development Agency, created in 1968 to settle Tibetan refugees in Karnataka] promised to help raise funds. Bablu aged 22 in 1978, arrived in Guttur, A.P.,in a tonga to join Bedi. He says: "I was fantasising: we were going to change Anantapur. I was then, I must add, an Anglicised Bengali with no Telugu." Dreamers need no qualifications, though. He was to stay with Young India for 12 years.

Mary was born in Idikki District, Kerala in 1956. Her folks were liberal and had made her feel proud and equal to the man's world out there. When she finished her Masters in Social Work, she asked her parents to let her travel in India for a year. The logical first stop was Anantapur where her brother was already working with Ferrer. Coming from wet and lush Idikki, the near desert that Anantapur was, unsettled her.

Ferrer suggested that she go and work with an organization called CROSS in Hyderabad area which was doing very radical work in those days.

Arvind was to make a difference in a most daring way, but that's for later. He appeared for the public services examinations and as he waited for the results, took himself away to Mother Teresa's and Ramakrishna Missions. "I spent some months travelling in Bengal and the North East. I began to realise how backward these parts were. Was it just poverty? Then why my own Haryana, where there is no poverty at all, is backward with illiteracy and male chauvinism?" He had no answers yet to what holds back a community from development; but he had a good set of questions. And that's always the best way to start.

Babu mole:

In 1992 he joined the Indian Revenue Service [IRS] and was posted in Income-tax Commissioner's Office in Delhi. Within months, he began to be aware of the silent, collective extortionist machine that his department was running. Citizens were being denied the services that were their right. By withholding information, the department kept the public in darkness as to where their cases stood.

Rights existed on paper. But the process to access them was muddied by the civil servants. It is this that led to corruption, dependencies and backwardness. The malaise is not poverty of incomes but that of information. He now recalled the paradox of Haryana and the North East and understood what was common between them.

What he discovered was not some great, subtle truth. It is obvious to anyone who thinks things through. The difference that Arvin Kejriwal, IRS made, was that he decided to do something to fight back the system he himself was a part of. He turned a mole.

Sprouting slogans:

In Kailash Bhoruka a Chartered Accountant and Col Pandey, Indian Army [rtd.], he had two able co-conspirators. Arvind taught them the rules, the ways of the department and the procedures. They met in secret and evolved a strategy. Thus began in the year 2000, an association christened, Parivartan [Change].

But we must go back a little, to discover how this political will emerged. Dr Sekhar Raghavan, a professor of physics was one of the first to realise the imperative of saving rain water for Chennai. Chennai has over 1200mm of rain fall per year but routinely lacks even drinking water, whereas a rain starved Rajasthan survives reasonably. What Chennai needed to do was to save the water that fell as rain. Its Ganga was in the skies. the city could link to it with RWH—right now. Raghavan was one of the first to preach RWH. He installed a RWH system in his house and began to organise his neighbourhood.

In far USA, Raghavan's activism made the Chennai-born Ram Krishnan recall how his mother would wake up at 3 am to collect water from a capricious tap. Ram and Raghavan connected and formed the Akash Ganga Trust. The idea was to raise awareness about the effectiveness of RWH as a solution to community water needs. They went on to build the Rain Centre in Chennai where the simplicity of the RWH idea was show-cased. Ram raised Rs. 400,000 and the Centre for Science and Environment [CSE] chipped in with support and inputs. It's a small residence converted into a resource centre. On Aug 21, 2002, Chief Minister Ms. J Jayalaithaa visited this modest building to inaugurate it. That was how it came about that RWH gained everyone's mind-share.

The proof is in the well:

Within a year of that date, a majority of buildings all over Tamil Nadu—and Chennai in particular— had RWH systems in place. Alas that year, rainfall was deficient. But even then results were dramatic enough to amaze and delight everyone. Water levels in wells across Chennai rose. Brackish water tended to get sweeter. There was less flooding in the roads. A lot of the money earlier spent on tanker loads of water, stayed in wallets.

Chennai was on a roll. Today, almost everyone across age and class is a believer. People brag about their wells like they once did about their children. Clubs, schools, hostels, hotels began to rig themselves.

Catch India:

In Patna, chasing a promised job, Pathak was not driven by that memory. He was looking to feed himself and his young wife.

To today's young educated Indians who can switch jobs with ease, name their salaries and expect not to retire from the job they begin at, getting and holding a job in India of the sixties would read like chapters from Catch-22.

The Centenary Committees's own term was nearing its end. Chief Ministers changed frequently. Salaries were just numbers in books, not money you received in hand. There was no Rs.600 job— instead there was a temporary one at Rs.12 per month. That too was threatened because of a perceived temerity towards superiors. Pathak hung-in there in hope of a 'permanent' job someday."We got by, selling trinkets from my wife's jewel box," says Pathak.

But an extraordinary meeting took place in 1967 that would concentrate his mind. Rajendra Lal Das, then 65, was a member of Sarvodaya movement, that worked on Gandhi's social concerns. Within that, Das had kept a firm focus on scavenger liberation or Bhangi Mukti. He urged Pathak to devote himself to the cause.

A clean-up caste:

There have been some persuasive arguments to pin the origin of the scavenger class on Muslim conquerors of India: it started for the convenience of their ladies in purdah. There is some truth that they used captured warriors as porters of night-soil. There are clear references however, in ancient Naradiya Samhita and Vajasaneyi Samhita to designated slaves —Chandals & Paulkasas, for example— for cleaning up toilets. Those two castes are referred to in Buddhist times also. The Mughals may however have introduced the bucket-privy and created a new caste label called Mehtars. Finally, the catch-all, derisory name, Bhangi for these abused people emerged.

In 1931, when India's population was a fourth of what it is today, the census reports nearly 2 millon Bhangis.

If Damu's path to their meeting was from the bottom up, Nandana's was from the top down. Her father Pattabhi Rama Reddy is an activist and an artist. Her mother, the spirited and talented Snehalata Reddy refused to be silenced by Indira Gandhi's Emergency, was jailed and paid for her convictions with her life. The Reddys are fighters for justice. Nandana was a natural trade union lawyer. She saw Damu's energies and began using him for meeting workers at factory gates.

Saw them standing there:

And that was how it came about that he saw them standing there. They were bewildered children watching the talk above their heads among adults. Soon however, they were to change Damu and Nandana.

A little research showed that 40% of all work-force in India at that time was made up of children. And yet, even the rights that workers enjoyed slipped past them. Unlike adult workers, who usually had families, these children were often from the streets, abused and kicked around.

Damu began organising children of Bangalore's streets into groups where they could share their experiences. Each child was living through a hell as a given, from which there was no escape. Damu decided to sublimate their miseries by turning their experiences into a composite play.

In 1984, Damu's children staged their play for Ramakrishna Hegde, Chief Minister of Karnataka. "It was a compelling narration of the horrors working children face," recalls Damu. "A young boy acts out all his agonies. He braves them all because of a will to live but the odds against him keep increasing. The climax was when he couldn't cope any more-- we had him run across to the CM, tug at his sleeve and ask, "Sir, is there nothing you can do for me?"". Hegde was in tears. So was Rajiv Gandhi, when the children at Hegde's behest, staged the play again a few months later in Delhi.

The neglected Pandava:

Wheels of India's ponderous state began to move. The Gurupada Swamy Committee was set up to draft a bill to protect children's rights. A law was enacted in 1986. It is not without its flaws, but India was a pioneer nation to focus on the plight of children.

Damu and Nandana had established The Concerned for Working Child [CWC] in 1980 to focus on this neglected area. By 1986 they had caused the parliament to pass a bill. That raised awareness about children's plight all around. The press began to cover the issue. Children had come into focus.

Resettling the mind:

The trauma of resettling in refugee camps, starting life again began to change the young man. He doesn't say explicitly, but at some point then, he decided not to marry. There was work at hand. Looking for business opportunities to feed his family, helping refugees, teaching children and so on. He got sucked in.

What or who changed him is difficult to tell, for the man himself is not given to expounding on his inner life. His bookshelf is lined with Gandhi books but also on Guru Nanak and an eclectic clutch of spiritual leaders. On the wall are portraits of Ramakrishna, Ramana, Aurobindo, Sufi masters, J Krishnamurthy and several others. Prominently, Nawabhai, his mother.

The strong woman's selfless work for the family and her grit seems to have deeply influenced Dada. Some years after, the family left the refugee camp for a proper home, a single room in Chowpatty for 20 members. From here, as their small business picked up, they moved to a proper apartment in Mahim, in the 1960.

It is not easy cope with so much in 20 years: rage, imprisonment, displacement, penury and renewal. Millions have however gone through hardship caused by the Partition and have moved on. Not many have retained a robust appetite for serving those in need. Dada has.

Doing the little things:

There was the logistics of settling waves of Sindhi refugees in Kalyan, Kurla and Palghar camps. He began to teach and administer a school for children. Not surprisingly, widows were everywhere in fifties. Dada began a subscription fund to distribute small sums for their maintenance.

There was the family livelihood to look after as well. Several partners pooled their modest savings and began a lending consortium. This is a business that suits the Sindhi native genius. This business model spreads risk. Family fortune began to smile. In the seventies they also began an auto-parts factory in Agra.

As soon as he had the sizable sum of Rs 2 lakhs as his share, Dada the bachelor, used it to create the Nawabhai Khimandas Lakhiani Charitable Trust. He lives a frugal life and invests shrewdly and so has been able to make this fund go a long way.

Desai had internalised what Gandhi had said to him:"Rural India is poor because rural people are drastically under employed". He had guided all development work at BAIF, towards creating livelihoods in farmers' own habitats. Tree based farming among tribals in Gujarat, maximising yields from rain harvested water in Tiptur and cattle based incomes everywhere, were showing promise. BAIF was developing many deliverable farm technology packages. Above all BAIF had a vast army of committed men, who were willing to work for very modest salaries with little creature comforts, in drought prone parts of rural India. BAIF has gained a deserved reputation as an organisation that can manage large developmental projects, with the least overhead and zero leakages.

In 1996, when the European Union wanted to channel Euro 20 million for a programme to transfer technology for sustainable development, it came to NABARD [National Bank for Agriculture and Rural Development]. BAIF was picked as the logical organisation to design, implement and manage the programme.

EU and BAIF come together:

The grand plan was all-round development of 33,000 poor rural families in 5 states. Dr Bhat's mandate was to work on 2500 carefully chosen families in 22 villages around Surshettikoppa. They were given Rs.39 million for 7 years. If you work that out,assuming an average family size of 4, the budget was Rs.46 per person per month, inclusive of administrative cost. How did Dr Bhat's team go about making that sum matter? In a few words, "by honesty, devotion, skill, hard-work and total identification with the people".

First of all, the ten men who implemented the programme, fanned out among the villages and started living with the people full-time. They then began a survey to identify the 2488 beneficiary families out of a total of 4800.They used 20 sensibly weighted criteria to detremine who needed help. A man with 100 acres in the wilderness may be poorer than one with an acre by a river. They picked 1780 families with between 3 and 4 acres, and 708 landless families.

"Then came the great war. There was a huge shortage of yarn and we were out of work. I then heard there was a large stock of unusable cotton, lying at the Mangalore Khadi Bhandar. Everyone had declared its yarn unfit for spinning.

"I examined it and brought a sample lot over. I spun it and with some care, I could weave it. The Khadi Bhandar was delighted. They thought me a master-weaver. They commissioned me to convert the whole lot and spent the princely sum of Rs 30,000 on my word. I put a charkha in every home in Brahmavar and set up seven looms. We began to turn a warehouse full of dead cotton into good cloth. Gandhi was as good as his word. We spent the war years in reasonable comfort.

"The Khadi people then sent me to their ten acre farm in Moodbidri to revive it. There was a goshala, a weaving centre and agriculture to care for. I was paid Rs 25 a month. It was hard life with our three children to feed. I was there for four years. The extreme poverty nearly broke me.

"Post-war, famine was stalking the land. The British knew how to march around and terrify people but they knew nothing about managing a crisis. What do foreigners know who are not born to this land, who have not experienced its truths? Gandhi did. He urged people to return to the land and grow food, just food. I knew he was right."

Back to Gandhi:

Cherkady Ramachandra Rao pauses with a soft smile. He looks into the dense stand of trees and plants. We eat some sweet-sweet pineapple chunks just out of the ground. He resumes his story after a while.

"We returned to Cherkady. My brother-in-law gave me a cow and this patch of land. It is a hectare. He had no use or plans for it. It was barren, with some water in a ditch. Despite reasonable rains in these parts, no water ever stayed on the land for long. I built a hut and the five of us moved in. The cow fed us all. I sold the milk and we ate whenever we could.

"I began to scrounge for seedlings and planted them all over. I would walk about wondering what to do next. There was no water to grow paddy. I raised some vegetables after deepening the ditch for some more water. I spent most of the time shaping the land to harvest rain water. That was the scene 57 years ago, and I am still here, a very contented man.

"Slowly the plants and trees grew. I never wasted anything that arrived on this land. All fallen leaves and cow dung, were spread around the young trees.

"I had built my toilet based on a design by Gandhi. It was a simple pan set into the ground, the outlet had a trap door and looked down on a pit layered with leaves. There was a rudimentary privacy screen around it. After each use one poured just a mug of water and that dumped it all into the ground; the trap door shut again, sealing out all odour. One then went around and emptied a small basket of dry leaves over the dump in the pit. Every year or so I made a new pit and moved the pan to it. In about six months the previous pit awaited me with rich manure.

The Chinese Cut:

World Bank President James Wolfensohn attending the 'Conference on scaling up poverty reduction' in Shanghai in May, 2004, has heaped praise on China. The UN News site, no less, reports this: "Wolfensohn said the Chinese Communist Party's five-year economic plan was a good example of effective poverty-reduction strategies. "Shanghai is the obvious place to start considering ways to reduce poverty," he said. "There is something here we need to learn about constancy and good management." ". Hilary Benn, a British politician is quoted as saying, "China shows what can be done with the right circumstances and the right policies." Mark Malloch Brown of the UNDP said, "China took the lead in its war against poverty rather than relying on development agencies to steer its course."

High praise indeed from those manning the bulwarks of the Free World. Reports such as these get mirrored around widely with headlines tailored for the local readership. Indians too have begun to make sentences starting typically with, "If China can do it, why can't India... etc, etc"

What are "the right circumstances and the right policies" that Benn is referring to? Indians must know. And never forget.

The similarities:

China's achievements, as parroted, are formidable. In the 25 years since it took to the capitalist road, poverty has fallen from 50% to less than 10%, GDP increased from $360 billion to $12 trillion, its ranking in world trade climbed to four and its average personal income, risen to today's $1000. China's strategy to achieve all this—in strictly economic terms—can be simply stated thus: remove all barriers to growth in a controlled area, viz the eastern seaboard, create a boom there mostly through huge investments in infrastructure, and then take the prosperity in a bag, for distribution in the vast hinterland.

That in a nutshell, is the China story that so seduces impatient Indians. They wonder how, two similar countries can have such different states of development. On the face of it yes, India and China are similar. They are similar in population, culture and began their independent existence at about the same time. But there the similarities stop and the contrasts begin, highlighting which is the purpose of this essay.

JK's original bid to acquire a 1000 acres for his school had not quite succeeded. His loyal colleague C S Trilokekar had in the 1930s, gone from village to village in a bullock cart and assembled 300 acres, which were largely bereft of trees. Overlooking this near desert, were barren, rocky hills all around. The annual rainfall of 700 mm, while not immodest, meant nothing given the bald hills and the tree-less valley. It was in this landscape that early experiments in learning were made.

The School's experiments to evolve a way of imparting education yielded some form in the 1970s during the tenure of Dr S Balasundaram as its Principal. Balu as he came to be known had followed the genial Gordon Pearce. It was during Balu's tenure that Radhika Herzberger, the current Director, arrived as a teacher. N Subbiah Naidu joined as a Physical Director. Dr N K A Iyer was the Estate Manager. S Rangaswami, who was a lecturer in the Indian Air Force joined as a teacher and broadened the environmental consciousness of the School. JK himself, seemed to be devoting a lot of his time to Rishi Valley during the seventies. He seeded two significant initiatives. In 1976, he started a school for children in the surrounding villages. He also urged that the School take to greening the campus and the land beyond as an active part of its curriculum.

Greening heart:

Iyer, the Estate Manager began an extensive planting programme on the campus, involving students. He was a naturalist and a hands-on man. Iyer began the tradition of the School declaring a holiday whenever it rained well enough for seeding, planting and bunding. Students would swarm out of classrooms and dig into the soil. [Iyer, after leaving the School, was to create his magnum opus in Kolar District of Karnataka. Read that story here.].

Rangaswami, in addition to being an experienced teacher, is a man who has truly imbibed the essence of JK's teachings. Which is this: the only worthwhile religion for mankind is, love for and identification with nature and all creatures upon this earth. He is today, into his eighties but retains a sparkling mind that is passionate about ecology. "When I first dug a small pond in 1975, I knew nothing of water conservation techniques," he says candidly. "I was looking to tempt birds to settle in the emerging woods." They dug another water body up the south hills and called it the Last Lake. Recurring years of drought earned it the rib that it was a 'Lost' Lake. Birds did begin to come, though. Rangaswami took to teaching ornithology both as a fun activity and as a technique to gauge the health of the environment. Students were co-opted into becoming observers and reporters of bird arrivals and behaviour. Rangaswami has remained the snake man of the School, and a fairly busy one as an abundance of small game has bred a variety of snakes. But we are getting ahead of our story to 1990. It is still the 1980s in our narration.

Merging streams:

Neither Greg nor Bernie grew up in Goa. Bernie was born in 1955 in Andheri, Bombay, one of seven children of a post office superintendent. She remembers herself as a rebel and something of a feminist even at a young age. Going through college, she held many part time jobs-- at a stone crushers for instance. She may not have been actively aware then, but her mind had begun to store away inequities in society. She was the telephone operator at Almonard when a workers' strike occurred. She was appalled by the management's callousness. "I would leak information to the workers and take messages for them," she says with a chuckle. That spell at Almonard made her want to go away and see how 'India' lived. Bombay seemed a poor place to find that out.

Greg, though born in Goa -1951- was taken away to Bombay when he was six. He was a studious, inward-looking young man. Family moved again to Ahmedabad when he was 13. It was there that he was impelled to become a priest. He was a natural teacher and mathematics was his favourite subject. It seemed education as a mission would be served by his becoming a priest. After high school the promising scholar entered a seminary in Ahmedabad. In 1981, he was ordained a priest in the Society of Jesus. The church nursed great ambitions on his behalf and sent him to Vidya Jyoti, a centre for higher studies run by it. His reputation as a teacher grew and he was marked for great responsibilities within the church.

Bernie meanwhile saw her first 'Indian village' in Bihar. As a Bombay girl, she was astounded how different, life was in a village. How much they endured with cheer and resignation. Workers at Almonard for whom she had raged, had been in clover by comparison. They at least knew what laws entitled them to. She saw in the villages around the ICI explosives plant and the Tenughat thermal station in Gomiya, Bihar the environmental degradation that unaccountable development brings.

Her true shock was yet to be. She and a few idealistic young people saw the transformation of well integrated Santal villages into a mind-blown, disrupted community losing all its self-esteem. All because of the rising Kushmandu dam near Alirajpur. For five years between 1988 and 93, Bernie and her small band of friends lived among the villagers and tried to form them into a unit fighting for its rights. They had little or no money, but they were full of passion and grit. They failed.

James Garthe's solution is along these lines, and it overcomes most major impediments in plastic waste management, such as:

1-- Nearly all known plastic re-cycling --or, down-cycling-- methods need sorting of waste by chemical type, a task that requires specially trained eyes

2-- Other pre-processes like cleaning, shredding, drying are often required, which are space-, capital- and labour- intensive.

3-- Plastic waste is dispersed, dirty and fluffy. When stuffed in bags it is too voluminous and uneconomical to transport over long distances.

4-- Down-cycling plants are too few, centralised and, capital- and skill- intensive, and far away from where waste is generated

5-- Energy put into reclamation is often higher than the energy realised in the product, reducing the whole exercise into one of social correctness, without any hard economic value

6-- Markets for reclaimed products are too specialised, controlled; therefore, realisable prices are arbitrarily set.

In short, the logistic, technical and marketing realms of plastic waste management are too opaque, specialised, unfriendly and uneconomical for you and me to be fully involved. The Garthe process addresses and solves all these problems.

The Garthe machine is a hydraulic compactor with a heated die. Roughly shred and cleaned waste is fed into the hopper, from where a ram pushes it into the heated die. At exit, the extrudate is sliced by a hot-knife into nuggets.

Without bias:

As an engineer with the Penn State University working with farmers, Jim Garthe was struck by both plastics' usefulness in agriculture --and the menace they become, as waste. He is therefore a man without any bias in the on-going debate on plastics. About 9 years ago, he built a small table-top machine which would compact rudimentarily shred mixed plastic waste and extrude them into well compacted sausages. These are then sliced by a hot knife into 'Plastofuel' nuggets. The nuggets may then be stored forever and transported economically.

In the Garthe machine, the die is heated just enough to fuse the outer skin of the nugget. The energy required for this is minimal. It is in fact a compaction process, readying the waste for storage and transportation. The calorific value in the plastic waste remains trapped. Thus, the energy gained from nuggets is more than what was put in to create them.

But of the three young women who founded the Shristi in Bangalore in 1995, only Suchita Somashekhariah was a mother and her children needed no special care. But she had been driven to this calling because a cousin's child had been special. In 1984, a road accident had killed that child and a few close relatives. Suchita reacted by joining the course for special educators at KPAMRC. Meena Jain was raised in Mysore in a family that had fallen to hardship after her father had died early. "We were poor. Mother worked hard, raised and educated us. But that didn't stop her supporting a few children poorer than us," says Meena, by way of explaining how she has committed herself to serving others. For Sharon Watts too, her mother was the inspiration. Sharon was a bright student and her father wanted her to be a journalist. "But Mother made up my mind without ever trying to influence me. She was a tireless, smiling nurse in Whitefield. Her obvious happiness and contentment struck me deep," says Sharon.

Everyone's darling

Neeraj is Merry Barua's only child. Twenty years ago she discovered he was autistic. Looking around, she realised, there was no organised counsel or help. So Merry took herself to the USA and learnt how to care for him. How? She closeted herself alone with her son in a room for 11 long months. That helped her understand this puzzled visitor from another planet

In 1991, she started in Delhi, the sub-continent's first school --'Open Door'-- for special children. Since then her reach has grown nationwide through her resource centre, Action For Autism.

Merry Barua is widely acknowledged around the world as a pioneer and tireless worker in the cause of autists. She is an educator, communicator and social and political activist. Above all, she is an inspiring role model for many despairing parents.

When she was a baby, her grandmother would call her, 'Meri Jaan' ['My darling']. And that's how she got the unusual name, 'Merry'. Her grandma had been quite prophetic. But not entirely-- she didn't know Merry would become more than just *her* darling.

eMail

Many useful autism links

_____________________

For close to 30 years, parents in Kolkata have been running the Indian Institute of Cerebral Palsy. Learn more about this private and volunteer initiative by unknown Indians, and maybe support them. Here's the link.

Fuad knew he had a hurdle. Given his specifications, each of his dream loos would cost Rs.10 Lakhs. And that is big money in India. He sat with his indulgent wife and daughter and discussed the deadlock. Suddenly Mehru said, "Hey, if it's going to be upmarket, why don't you get upmarket advertisers to support it?"

In a few days, Fuad had made a model, prepared a business plan and a formal request that said more or less, "just give me the permission and I will provide a service India can be proud of". He got the permit. He reminisces now: "Yes, it's not simple in India. But doors do open for those that are sincere. Most of the time our bad mouthing the Indian system, is to do with our tendency to seek alibis. I found a receptive bureaucrat and a politician who backed me."

The Great Wall of Ads:

But no one was going to give him money to build a loo. He formed Fumes International Company, and decided to put his own savings on the line. "If I am an entrepreneur worth my salt I must take risks," he told himself. He began to build his definitive toilet in one of Delhi's in-places - Khan Market. He lavished all his care and attended to every detail. Mehru an interior designer was with him the whole way. It was not to be just a tucked away loo, but a high profile object of style. When it opened in late 1999, it was a hit at once. Almost always in India, we build great edifices but pay little attention to how we would maintain them. Fuad was firm from the beginning: "my toilets have to be inauguration clean forever." He had spent time in planning maintenance, training his staff and they paid off.

After five years they are spotless. Two attendants clean after every use. A watchman guards it between 10 pm and 7 am. Visitors are delighted. An affluent lady says she uses it all the time. Bernie Fernandes, a working woman says, "I feel so safe, relaxed and comfortable." A highly impressed Robert Kinfarley, the head of World Health Organisation [WHO], in Delhi sent his staff to Fuad's toilet for training. Clearly user endorsement was gathering. Visitors are charged a token Rs. 1 and Rs.2, just to induce a sense of responsibility.

Though it took him over six months trying to persuade advertisers to support him, he was certain he had a USP: foot falls of the spending kind. Early mind blocks were blown away. Big names were eager. Fuad's toilet walls are not cheap to advertise on. The income from ads enables him to pay great wages, make a nice profit and build more toilets. He has 11 in Delhi so far, in places like Connaught Place, Lodi Gardens, Sundar Nagar, Golf Links etc. Each is a unique piece with marble, granite, chrome, plants, aquarium and above all with that heavenly peace that reigns in great washrooms. Fuad is forever making the rounds. Are the sills clean? Is the soap in the right place? Is the plumbing drip free? He's a perfectionist.

The greatest world spend is probably on personal products. The Indian garment is no longer cheap sweat shop produce. Indian companies are buying brands or even better, creating them. And they, label their garments for the discerning buyer. Salman Noorani's 'Zodiac', is probably the first Indian company [--since the 1960s] that realised the value of branding. Its garments command an average of $60 a piece. Zodiac has three design centres worldwide.

New York Times mused in May, 03: "Considering that India is historically credited with giving the world paisley, seer sucker, calico, chintz, cashmere, crewel and the entire technique of printing on cloth, it is anybody's guess why India barely registers on the global map of fashion." It went on to report what Jaqueline Lundquist, wife of a former US Ambassador is doing about it. She says,"Western designers have been coming to India and 'borrowing' for 50 years. It's not fair that all these American designers should get the glory for Indian design." She is actively redressing this style-piracy.

Indian fashion was said to be *in*, a few years ago; it is now clear it will probably to stay in. Take in this typical news: Europe's leading jewellery company Hammer & Sohne commissioned Sadhak Shivanand Saraswati, 'a spiritual artist' to design a series for them. Such news is commonplace these days.

In the 'hard' sector:

You may dismiss fashion as 'soft' sector. But how about this: Dilip Chhabria designs an Aston Martin, the car deemed worthy of James Bond. Or the now routine pieces on A R Rahman: that he teams up with Andrew Lloyd Webber or that he has just finished scoring for a Chinese opus, predicted to rival 'Crouching Tigers...' Or that Samsonite is to locate its 'Global Design' centre in India. Or that Srinivasa Fine Arts, Chennai designs and distributes upmarket stationery like diaries, calenders, planners, albums etc through Neale Dataday, UK and retailed through the likes of Harrods. The point is, India is climbing steadily up the value chain on all fronts.

The 'hard' sector is not visible to most Indians. Out there, small and medium businesses are staking new territories with products that range from bone china to car batteries. They succeed because, companies like Tata Motors with their Indica, Mahindra and Mahindra with their Scorpio and TVS Motors with their series of bikes have shown that Indians can design from scratch and meet world's quality requirements. Because, Indian companies are beginning to win prizes for quality, like the Deming and TQM -- a domain that seemed reserved exclusively for Japan.

Her father's last words to her were: "don't ever lose faith in India." Her mother --ever the realist-- left her a vignette: "when I was the young child of a poor priest, my cousins were wealthy. They would grudgingly give me a sweet-meat but only after pointedly licking it on all sides. Don't ever forget that such pettiness happens all the time in this land. They can scar lives."

With parents suddenly removed, Anuradha discovered that life was a serious matter. Her grief and reflections on her parents' values brought on a physical stress, a depression even. A few years before, she had visited Barka Koppa and was treated to the most exuberant bonhomie by her just re-discovered kinsmen. And yet all around her was some of the most casual inhumanity. Lost for answers, she became a near physical wreck. Was it a psychosomatic consequence of bereavement? Her physician had no such doubts: he pronounced her ailment 'spondylitis' and fitted her with a collar. Anuradha wore it for the next several years and cultivated a suitable stoop. In 1998 her younger daughter Shamika who had thriven in European schools found herself a misfit in an Indian school. Anuradha took her out of the system. The list of 'whys' was lengthening.

Manu shows the way:

She decided to 'do something'. "I shall deliver nutritious biscuits to scrawny children everywhere," she told herself. She began a trust named after her father, canvassed wealthy sponsors and the project lurched along. But somehow it seemed too superficial. There was more down there that needed to be faced. And that evaded grasp. So the collar stayed.

One day in 2001, an acquaintance steered her to a healer in Giri Nagar slums. The lady, a poor Nepalese whom Anuradha calls Mataji, was direct. "Your collar is a decoy and leads you away from what you should be doing. Get rid of it and start examining yourself through involved work for the needy." And that wisdom from a simple, unlettered, poor woman instantly turned Anuradha's life around. The collar came off after 9 years, without further ado. The bemusedly named Project Why happened the moment she met Manu, the young man who would provide a meaning to her life.

She met him as she sat waiting for Mataji. "Though physically and mentally challenged, Manu had spent a happy early childhood, tended and cared for by his mother," she says. "Mother passed away when he was a young lad. His sisters in their own way cared for him too but they were married off at an early age by their alcoholic father. Manu lived on the street, dirty, soiled, and neglected. The neighbours fed him, but like one would feed an animal. Children threw stones at him. He was abused in all conceivable ways. Manu was made to beg but the money was snatched away from him. No one touched him, no one hugged him. He learned to bear it all. When things became too much, he let out the most heart rending cry that no one heard."

Revival begins:

By 1977 Thathachar had persuaded the Karnataka government to commission an Academy of Sanskrit Research. He was given 15 acres in Melkote, if he would set up the Academy; funds for building and running the centre however was not assured. He had to depend on his considerable reputation and energies to raise the money. He took the challenge on. He quit his job as professor and returned home. An adventure awaited him.

Thathachar stood on the windswept ridge allocated for the Academy. Years of deforestation and water run off had rendered it a rock strewn moonscape. From the valley below the wind howled. Most of the stone-stepped kalyanis lay in disrepair. The Academy buildings and research teams seemed far away and impossible.

He began at what he knew. The line of Ananthalvan of which he was the current heir, had always been the chosen one for gathering and bringing various strictly specified flowers for worship. The 'sthala purana' ['local history'] extensively described the flora and fauna of the hills. Thathachar decided to recreate a garden that will hark back to the gentle times.

This was easier conceived than done. It was then that Thathachar re-discovered the Hallikar bulls. These had been Tipu's beasts of burden dragging his guns and carrying his rations and other supplies to war. They have a fine head and their horns crown them well. They are fierce, fast, strong and loyal. It was said Tipu would tie flaming torches to their horns and drive them to speed at nights; it was Tipu's 'shock and awe' play.

Thathachar recruited this proud, handsome, native species for a new enterprise now, and began to breed them. The Hallikars were used to bring soil, water and materials to the Academy site which was up a gentle slope from the temple town. Soil was strategically filled in the hollows between rocks and he began to plant them with jasmines, sampige and other Indian flowering trees and shrubs. As the garden formed in this hard rock place, the professor --without any place to research Sanskrit yet-- began to observe the emerging world around him. He dipped into the texts to learn of 'rishi-krishi paddati' or the system of zero cultivation. His growing Hallikar herd and rising grove meshed with each other and encircled Thathachar. He doesn't take organic material to compost somewhere. He lets material fall where they might. He takes raw dung and piles it over organic matter. There they lie and decompose and create soil again. Today after 24 years of this practice there are 300 species of plants growing in mixed wilderness. There are 26 species of jasmine alone.

A 'gunta' for a pond:

The objective was to benefit the poorer farmers in the upper reaches, by giving them dependable water resources. BIRD-K used all the modern techniques to map the geology, topography and existing water resources. Of greater importance was the social mapping. Using what they called 'participatory rural appraisal' they had a sociological profile of the place. 'But telemetric data is no substitute to walking all over the watershed area,' says Reddy. 'nor can a social survey replace patient discussions to answer participants' doubts and queries." The project was to cover a catchment area of 1000 hectares of which 750 ha were held by 330 families spread over 6 hamlets collectively forming the Adihalli - Mylanhalli village cluster. All these holdings had given up any serious farming. Over the years they had seen sharp rainfall over just a few days wash off all the top soil and enriching the valleys below.

By 1995 the BIRD-K master plan had been ably piloted by Dr N G Hegde -- who had succeeded Manibhai Desai at BAIF, Pune -- and gained funding support from India Canada Environment Facility: they would provide Rs.8000 per hectare to be spent almost entirely on labour costs. But convincing farmers to set aside a 'gunta' or 33' x 33' per two hectare of holding, was not easy. Although the farms were practically non-productive, the average farmer felt he was giving away something for no direct benefit to himself. It must also be remembered that such a large scale proposal was without precedent. There was nowhere the farmers could be taken to see the benefits of networked farm ponds. [The Manjunathapura experiment --see box-- was smaller and did not include networking of ponds] It's a tribute to the persuasive skills of Reddy and his team that in the end, all the 330 farmers in the project area joined.

When rain water falling on hilly areas is unrestrained, it flows along the slopes, gathereing velocity and top soil. Instead, if ponds located at the same elevation are connected by trenches, water racing is arrested and water is made to dwell and descend slowly down numerous vertical paths. This in simple terms is the technique but the benefits are in the details as we shall see.

Doing it:

Guntas set aside for farm ponds were in a lower corner of the farm. In it a pond of 30'x30'x10' was excavated. The ponds were strategically located along the same contour line and interconnected by channels cut along the same elevation. On an average there are about 15 ponds per contour. Soil from excavated channels was piled high along the lower edges forming a bund. On these bunds fruit and fodder trees were planted to reinforce the bund and to make them productive. Likewise the soil excavated from ponds was piled along the edges and planted with vegetables, herbs and useful shrubs. Farmers soon realised that the surface area on these mounds were nearly equal to the land 'lost' to the ponds.

An Indian officer in the World Bank, Dr Emmanuel D'Silva heard of Professor Shrinivasa's work. He arrived in Bangalore rather excitedly. Soon a small team left for the forests in Adilabad, AP, on the border with Maharashtra. The Professor and his lieutenant Mr. A R Nayeem from SuTRA and Dr D'Silva from the Bank were joined by Mr Mukherjee and Mr Navin Mittal of the Integrated Tribal Development Agency [ITDA] in Utnoor. [ Mittal deserves to be especially noted. He had graduated from the IIT with a Gold Medal but then did an unusual thing: instead of flying out to the USA for a charmed life, he chose the IAS as the more meaningful option in life.]

Bettering the lives of the tribals was Mittal's mandate. Soon it became clear to the team what a hard one that is. Listen to Nayeem: "Till Utnoor it was familiar India. But the last 30 km to Chalbardi --a Ghond tribal hamlet of 21 homes-- was another India. Our Jeep crawled over a rock strewn alignment called a road. We walked a part of the way. It is an experience never to be forgotten as the sole reality for many Indians." At Chalbardi they found a tribe of Indian citizens who were grim faced about electricity. They had known it only on their occasional travels out of the woods and had given up hopes of it ever arriving in their village. When the Professor talked of bringing it to their homes in six months, they wearily looked away. When he said that they could pay for it with the abundant Pongamia [Karanji in Hindi, Pongam in Tamil and Honge in Kannada. It is a.k.a Indian Beech] seeds strewn on the forest floor they gazed at him incredulous. He then did the wise thing: he invited them to Kaggenahalli in Kunigal Taluk, Karnataka to see the SuTRA demonstration project. Govinda Rao of Chalbardi, soon led a small curious band.

The Professor marvels: "They made their visit in April, 2001. And they caught the bug. When we went back to Chalbardi two months later, a nursery of 20,000 Pongamia saplings greeted us. Govinda Rao was hustling us: "We can give you the seeds for ever-- when is electricity coming?" "

Lab to land:

If the SuTRA demo in Karnataka was the laboratory that proved the idea, Chalbardi will earn its place as the village that took the idea to an India out there. Two off-the-shelf gensets of 7.5 kva each were installed in a hut. The hamlet was wired. Karanji oil engines powered a decorticator and an oil mill. And in June, 2001, right in the middle of a forest, with no pylons, no pollution, no down-time and no bills to pay, darkness made way to light. People whooped in joy. Children raced round and round. And were delightedly, sternly told that it was time for them to sit down and spend some time learning. This self sustaining miracle cost just Rs.500,000 [$10,000].

First probes:

FoSS made two small test investments in late 2000. By now Arun Diaz, Vineet Rai and Jennifer Meehan had joined the executive team [Profiles of the key people who built Aavishkaar can be found here.]. Both the investment ideas they chose are worth looking at in some detail.

The first was an innovation by Mansukhbhai Patel in Gujarat. He had watched the painful labour put in by women and children in stripping cotton seeds of the Kalyan variety. Kalyan is sown for its hardiness in arid parts of Gujarat. But extracting the cotton out of the doughty seed was the price one paid. Patel was close to his fiftieth year and had done just ten years of schooling. But he came from a farming background and sensed an opportunity. He conceived and built a mechanised cotton stripper.If the traditional separation process yielded 20 kg/hour, Patel's machine stripped 600. FoSS invested just Rs.250,000 [$5200]. That was all that was required to nurture a major improvement. FoSS got back its capital in 5 months with 35% annualised returns.

The second investment in 2001,too occurred in Gujarat. Young Kalpesh Gujjar had struggled to pass class 10 but he had mastered computer aided design [CAD]! He lived in Gujarat's oil extraction country. He had many friends in the industry and often helped them out of mechanical problems. He would ponder the power hogging oil expellers and of the many ways they can be made efficient. He then built one incorporating his ideas. He replaced the sheaves and pulleys with a direct coupling. He built in an efficient planetary gear box, and arranged the whole for compactness. For the same yield, his Swastik Oil Expeller required 30 horse power, against the 90 HP average for the traditional plant. Its compact design required half the earlier floor space. Overall operational savings were 30%. After due evaluation FoSS again lent Rs. 250,000 in return for a pre-agreed 20%. The principal was returned within a year. Kalpesh went on to win the National Grassroots Technological Innovations Contest as well as Gujarat state's Dr.Vikram Sarabhai Young Scientist Award.

Many lessons were learnt from these two investments. One, that a good idea often stood to be lost for want of a relatively small sum of money. Two, the traditional exit route of venture capitalists --premium earned during initial public offering [IPO] -- is not available here. They must make do with a pre-agreed return, owner buy-back or rely on mergers and acquisitions. Three, management costs and evaluation processes had to be right-sized, without compromising quality.

Elango was a good student and so entered the A C College of Technology, Chennai to study Chemical Engineering. He tried staying in the hostel for a few months. But was disturbed by thoughts of having run away from his reality. He began to commute the 40 km from his village by changing many buses each way. In the village he teamed up with his old mates to try and put some hope and dignity in their lives. They formed youth clubs, stuck wall posters with reformist messages, organised study groups, gave special tuitions and tried a number of other heart-achingly inadequate activities. Elango seems to have intuitively understood the importance of human development but was lost for a platform.

Flying on reluctant wings:

The first technical graduate from Kuthambakkam was grabbed from the campus in 1982 by Oil India and posted in an exploration site in Orissa. For most young men in India to be on such a promising career belt is dream come true but Elango found himself tethered to his village. A brief holiday revealed his youth club members were drifting away. He quit his job and joined the Council of Scientific and Industrial Research [CSIR] in Chennai. Commutes to his village began again. His youth club revived.

In a while Elango was married to a young lady who was a chemistry graduate. Two baby girls arrived in quick succession. By then Elango had visualised a long term road map. He and Sumathy had many conversations and agreed on a plan. They would make a home in Chennai, he would take care of the children and she would do her Masters in chemistry. Then she would find a job and provide for the family and he would return full time to the village. He speaks feelingly of her: "I can't quite estimate her contribution in whatever I have done. Until I began getting some money from an Ashoka Fellowship in 2002, she has been the bread winner. She has supported the family for over a decade without a murmur and raised our two girls."

In 1994, Sumathy got a job in the Oil and Natural Gas Commission [ONGC] and Elango promptly quit his. Two years earlier there had been caste riots in the village. Kuthambakkam is a Dalit majority village. There had been upper caste taunts and mob fury in response. Vanniars fled the village. After about a week when they did not return, Elango began to make many trips seeking the scattered Vanniars and persuading them to return. He was but a young man in his early thirties.

Kuthambakkam: some facts

Kuthambakkam village where Elango lives is about 30kM from Chennai on the road to Tirupati. Soon after passing Tirumazhisai, turn left off the highway at Vellavedu and you begin the pleasant drive to Kuthambakkam.

The Panchayat covers a 36 sq. km area. It has a population of 5000 people in 1040 households spread over 70 hamlets. Kuthambakkam itself is a delightful village with numerous ancient small temples. Clearly it is a long lived habitat.

A vast lake irrigates 1400 acres. Agriculture is practiced in another 700 acres which are rain fed. Water conservation has clearly been a part of its heritage. Elango's leadership continues this tradition.

Though 55% of the population are Dalits they own only 2% of the productive land. There is only one Muslim family and about 4% are Christian. Mudaliars, Naidus, Vanniars and Yadavas are the other major castes. Caste barriers haven't completely broken down but at least there is no animosity. In the last year there have been about 6 inter-caste marriages. There are 10 college graduates now.

Village Republics :

Not many Indians are sufficiently aware of the impact of the 73rd Constitutional Amendment spear-headed by Rajiv Gandhi in 1993. It sought to create totally self governing villages with far reaching powers. A plenary of village people [Gram Sabha] was mandated to meet every quarter and elections to the office of Panchayat President [Sarpanch] was mandated for every five years. The intention was to create village level Republics. Tamil Nadu ratified it in 1994 and elections were announced soon after.

The Ralegan that he returned to in 1975 was as we saw, a heartache place. A drought in 1972 had crippled it further. Fist fights and vandalism throve around the liquor vends and the bazaar. Wood work from the now crumbling temple had been ripped out to stoke the stills. But there were some game triers at reforming this unruly village. A relief committee run by the Tata group was reaching out. Catholic Relief Society supplied food grains to keep off hunger. And then there was Ashok Bedarkar, a young professional managing the Tata programmes. Hazare began looking for a beach-head to start his campaign. Unmarried at 35 made him rare. And his giving away his pension money to the needy made him an odd ball.

Changes fit for Ripley's:

Prompted by his intuition and powered by the settlement funds from the army, he renovated the village temple. And began to live --as he does till this day-- in two rooms there totalling, 200 sq. feet. Slowly people began to come and meet this man with strange ideas on money. By now he had earned their trust and the Maharashtrian honorofic, 'Anna'. The road out of the village's problems had to be built with contributed labour or 'shramdaan', he lectured. Each of the 250 families had to send one volunteer per day per week. Each day's labour counted as a Rs.30 contribution and earned Rs.70 from the government. Thus began small watershed works. As soon as about 60 small bunds, check dams, trenches and percolation ponds had been built there was a dramatic change: water table rose throughout the village. Anna had changed a despairing mind set and set the pace for galloping changes.

Within three years farmed acreage grew from 80 to 1300. Farmers gave away over 500 acres in the catchment areas. Village labour engineered these for harvesting all the rain that fell. Soon they were raising three crops a year and exporting table produce to the cities and even overseas. They worked out a water use regime: water drawal and crop selection is strictly regulated based on the rainfall and by sounding the water table. Today nearly 90% of the arable land is farmed. Along the way, Anna persuaded the villagers to accept the 25 Dalit families as their own, fought off the liquor barons, chastened the wife-beaters [--he had them thrashed in public], drove tobacco out of town, began a massive afforestation programme, built 11 bio gas plants, a 65 feet dia. community well and as a crowning innovation, started a Grain Bank, at the temple: anyone can 'borrow' grains when in need and return when able, with a little 'interest' added. Not many borrowers these days, though -- mostly farmers come bringing a little of their surpluses to add to the bank's reserves.

A plot of land [3,300 sq. yds in area] near the Ghatkopar Railway Station was bought for the sum, with the help of a Government grant. Again the bank balance went to zero. No one was willing to lay the foundation stone for such an institute. 'Jai Ramji' [as Nandkishor was popularly known, for his usual greeting to all] himself was asked to do that: and in the name of God he did that.

He was again went on a fund collecting spree. This time he gathered seven donors, each committing Rs.3,000 [-- amount required for one class room], and the ground floor was ready. The then Chief Minister of Bombay Shri. B G Kher declared open the building and the first batch batch of 80 students moved into the new school by September of 1947.

Now came the period of risk. He went ahead with the construction of first floor without any capital -- purely on faith. The debit note rose to Rs.22,000. Again fate intervened. He collected a larger sum of Rs.31,000 from staging the famous play 'Deewar', presented by that kind hearted, popular actor Shri. Prithviraj Kapoor. Came Rs.44,000 from an unknown donor and the building had its second floor completed, barely within four years from the time the foundation stone was laid with no bank balance.

Here is a living example of that 'karmayogi' of the Gita -- a man who believes in doing his duty, leaving the rest to God. And God has never failed him. Yes, at times He severely tested this disciple of his but in the end He stood by him.

College takes shape: