Rural folks' cancer deaths are less talked about than their suicides, but the scale and causes are the same.Since 1997 Dr Debal Deb has been conserving 700 varieties of native rice that seed companies are trying to drive outAnshu Gupta's volunteers driven Goonj, collects, sorts and distributes clothes for the poorFor over a 100 years Olcott Memorial High School in Chennai has been giving free education to the poor.

An Indian foot:

The Jaipur foot costs about Rs.1,300 to make.[The beneficiary of course pays nothing]. It can be made by an averagely skilled team of five, which can produce 15 limbs a day. But that is not the end of its merits. It's a limb that is suited for Indian use. Wearing it, one can work in the fields, run, pedal a bicycle, squat on the floor or even climb a tree. In contrast, a prosthesis from the West is mostly cosmetic.

True art seeks no prize:

Pandit Ram Chandra Sharma's family has lived in Jaipur ever since the city was conceived. His ancestor sculpted the idol at the Amber Palace temple. Masterji has studied only up to Class 4 but his blood probably carries all the lessons he needs. He is versatile on paper, canvas, stone, wood, glass and metal. Being curious, he investigates every modern material and manufacturing process.

He is a fit 85 and rides a 50 cc moped every day to the Malaviya Nagar centre of BMVSS and potters around- experimenting, supervising, counseling and mentoring. In the evening, on the ride back, he stops at the vegetable market to shop for the family dinner. He is an uncomplicated man and evidently very content. Though many are agitated that he received neither credit nor a share of the Magsaysay Award money, Masterji himself has no grievance. In fact, he admits he could not have brought the innovation to the world's notice. "I am glad it happened and many have benefited," he says.

Recognition may have eluded him but the gift of art flows on in the family. His son Kishan Lal Sharma -who also works at BMVSS- has developed a knack for custom moulding cosmetic replacements for severed noses and ears. He uses an imported mouldable compound used by plastic surgeons. "You would be amazed how many people lose these in rural India." he says wryly. He tries to make an indistinguishable fit. He feels satisfied at the happy difference these small prosthesis make in people's lives.

Masterji is but one of India's perennial stream, insufficiently celebrated by the 'educated' classes. But for them, there would be no India story.

...

Plot No 20, Suman Vihar, Imliwala Phatak, Krishna Nagar, Jaipur 302005, Rajasthan

Phone Home: 0141-591214 Kishan Lal's mobile: 0-98280- 70311

Masterji's original creation was in wood and then aluminium. Later, while visiting a pipe factory in Hyderabad, he was struck by a narration of HDPE's virtues: light weight, low cost, mouldability and strength. He grabbed a few lengths and returned to Jaipur. In a few days he had re-invented the foot again. Today body coloured HDPE pipe is manufactured specially for BMVSS use.

To scale up delivery, BMVSS conceived fitment camps. These are held all over the country. Schedules are published at their site. Local chapters screen and line up people in need of prosthesis. Expert team leaves Jaipur complete with equipment and materials. There over several days, limbs are fitted practically at victims' door-steps.

By the way, BMVSS supplies more than the Jaipur foot. For a start, there are above-knee and below-knee prosthesis. For polio victims calipers are supplied. For those cases that cannot benefit from either of these, hand-driven tricycles and crutches are supplied. Of late, they have begun giving hearing aids, as well.

Back in the fifties, this process was already apparent to young Dr G G Parikh. Yes, he believed - as he does still- that the prevailing order must be constantly questioned and changed, but in the while, constructive work was necessary. One cannot sit and wait for that moment that will change everything. He began his medical practice at Grant Road and attended to the poor free. He responded to JP's call in the mid-1970s for a 'Total Revolution' and was jailed when Indira Gandhi perceived an 'Emergency' closing in on her. He campaigned for socialists he respected, in electoral politics.

But all that seemed too little. That's when G.G. heard afresh, what JP had been urging socialist friends for years: "We must do something for Yusuf". How quickly this fine fighter for a just India had been forgotten by the media and the establishment.

One time was not enough:

In 1961, G.G. started the Yusuf Meherally Study Centre in one room in Bombay. It was somewhere for socialist loyals to meet and discuss ideas. In such a meeting, someone suggested a one-day medical camp at Tara near Panvel. It seemed so do-able as G.G. himself was a doctor.

That camp opened G.G.'s eyes to a rural India that Gandhi was always focused on. "300 people came to that one day camp in 1967, looking for medical help. Most of the needs were trivial and yet they were not ever available before we came," he says. There was no way they could wind up and walk away. G.G. kept coming back every Sunday and soon Mangla joined him. As problems of rural life revealed themselves to the Parikhs and they responded to them, Yusuf's spirit settled at Tara.

Since that day in 1967, the Yusuf Meherally Centre, has come to sit on a 150 acre campus and is the hub of activities for 20 villages around it. Villagers are mostly of the Katkari tribe whose women have suffered due to abandonment and alcoholism amongst its men. Children have been denied education -and therefore, opportunities. Cash income was non-existent.

The most obvious solutions came first: a medical centre, a 30 bed hospital, women's support and thrift groups, micro production activities like oil milling, soap making, food processing etc and then of course the large school that we began this story with. Money has been forthcoming with moderate effort. "There is no lack of money in India when your work is transparent and results are obvious," says G.G.. He has raised close to Rs 1 crore every year for 20 years now,-most of it Indian- with which to develop the centre.

There are unobvious surprises as well at the Centre. An association with Shripad Dabholkar led to a pilot 10 Guntha Project run by Deepak Suchde. If proven, this can revolutionise food production in marginal lands. Then there is the G.G. dream to reinvent the Khadi movement to transform rural economy. The Centre also rallies every time there is a major disaster - from the East Pakistan refugee crisis of 1970 to the tsunami of 2004.

Planning disruption:

That is so simplistic that many technologists will react stating the many problems in the way. Alka was lucky she was sounding Umesh. He's a positive person who believes anything is possible. Ten years ago, when their son Akshay was just 8 and home computers were intimidating, expensive objects, everyone shooed the boy away from it. Not Umesh. That encouragement led Akshay to become at 12, the world's youngest Microsoft Certified Software Developer [MCSD]. The Zadgaonkar family was sent tickets to Seattle for a private meeting with Bill Gates. [Akshay, yet to finish college is interning with Microsoft at Hyderabad.]

So Umesh understands dreamers. He urged Alka to explore her idea. "He believed in me and kept saying it was only a matter of time and labour," she says. Young Sunil Raisoni, who runs the Raisoni College where Alka teaches was another man who encouraged her. She got space and permission to set up a lab in the college. Zadgaonkars sold an apartment they had and set aside Rs. 1 Lakh for equipment.

From the beginning Alka was clear that any process she develops should be able to handle any manner of plastics, with little cleaning or preparation. She was setting herself a harder target in a territory without maps. Her idea was to get a plasticised pool of waste to react with her proprietory catalysts to create hydrocarbon fumes that can be condensed.

She set up her experiment at Raisoni college and began trying various catalyst recipes. "I began with an awareness that it'd be a long series of exploration," she says. But she was not prepared for the length of that series. The temperature and pressure [-atmospheric] parameters were pretty much standardised; the only experimentation was with various catalysts. And yet, there was no sign of promise.

Then came Carver:

Three years into her experiments and with nothing to show, Alka was close to giving up. She began to doubt her ability. Umesh sensed the mood and brought home a Marathi book for her to read. It was 'Ek Hota Carver', a biography of George Washington Carver, the great black American inventor and idealist. Alka says,"That book shamed me. Here was a man who was black, denied parental love and racially discriminated. Yet he pursued knowledge that may benefit all and left his wealth for common good."

Carver carried her over the last mile. She resumed her experiments with a new vigour. Then came the day, Dec 13, 1999. She had set up that morning's trial catalyst and was in a classroom teaching. A maintenance staff came rushing at 11 am and said cooking gas was leaking from her lab.

"I knew at once that I had my winning catalyst. If there was gas, there would be a distillate too," she recalls. And there it was, a few milli litres of liquid petroleum recovered from plastic film waste. She sat down for a few moments to take it all in. And then she called Umesh.

Real education begins:

Those two years changed him - twice. First, here was true education at last. They were made to read 200-300 pages a day, analyse, quantify, conclude and present. Nothing could be learnt by rote. Interacting with bright students and faculty, this country boy thrived, amidst a high drop-out rate. At last his mathematical and inquiring skills were presented with challenges. He loved it there.

Then in the second year, he was changed again. "There was a maverick professor called S R Ganesh who made me realise what I should be doing with my life," says Vasi. Ganesh ran a course called "Internal Change Agent" that forced students to commune with themselves, facing questions like: who am I; how might my obituary read, if written today; what are my real strengths and talents; what'd I do if I had ten years left and so on. The crowning act was a report they had to write on their life's work standing at a point in the future. Vasi's life came together that moment and all his experiences fell in place. Life as a series of examinations to pass, was over. He had to work on the material he had been made a part of: primacy of rural India, the boom and the bust of rural economies and the wreckages they left behind in the form of depleted soil, penury and hopelessness of rural people. He decided that he was not meant for the corporate world.

As happens often, chance arranged for him to spot a brochure his classmate Trilochan Sastry, had brought back from his travels. It was of the Association for Sarva SEva Farms [ASSEFA] headed by S Loganathan. He wrote to ASSEFA. Shortly, Vijay Mahajan arrived to meet him. Mahajan is one of India's innovative development thinkers, a pioneer in micro finance. He was an IIT and IIMA alumnus and was working with ASSEFA in Bihar. He, Deep Joshi [then with the Ford Foundation], Aloysius Fernandes [an ordained priest who had quit the cloth] and a few others, proposed to form Professional Assistance for Development Action [PRADAN]. Its mission was to attact managemnt professional to assist NGOs. Vasimalai joined as founding staff member.

He arrived in Chennai deputed by PRADAN to work with ASSSFA. He was given a pay of Rs.1,800, less than a third of what the corporate world might have offered him. And the lifestyle was far removed too.

ASSeFa is one of those organisations that you wouldn't suspect existed, nor would you guess its origins. It is the keeper of lands handed over to Acharya Vinobha Bhave's Sarvodaya movement as Bhoodan [gift of land]. Vasi arrived and his rural upbringing at once made him comfortable among the ageing, austere Sarvodaya men. They were simple idealists with great empathy for the salt of the earth, but they were untrained as managers. Vasi as a professional manager took to writing proposals, raising funds, taking donors to villages and so on. He was drilling wells, planning livelihood schemes, working on education, hygiene and every obvious symptom of an unsustainable scene.

During all this time his native village was falling apart. It was in 1987, that the first realisation struck him with a numbing force. Where was the water to sustain things? He had busily biked through hundreds of villages but had barely noticed that traditional water works were being neglected. They had been drilling wells and installing pumps- but there was no water to pump. What was happening to Ezhimalai, his village was happening to all villages all over Tamil Nadu.

Coastal Regulation Zone [CRZ] laws, HR&CE lease terms, citizen's rights to peace, pollution control laws were all violated and no one seemed to care. In 2002 the Grama Sabha passed a resolution seeking eviction of MGM from temple lands. Fishermen demanded of HR&CE that MGM's lease be terminated and punitive fines levied for felling trees. They petitioned the Chief Minister. They even filed a writ in the High Court. Nothing seemed to make a dent on the business management skills of MGM. Their public relations matched that skill: far from cultivating a benign image, they chose a menacing, muscular profile. An attempt by its workers to form a labour union in 2001 was ruthlessly snuffed out with police help. That confirmed the image they sought. MGM's money and muscle were soon legends for miles around.

By 2001, the temple grove was gone. Gone too, the little shrine and pond. Bulldozers had created a vast, flat space, and hundreds of trucks carrying in red earth and manure transformed the porous, water charging soil into one fit for an emerald lawn. A 3 acre lush green party land was ready to welcome MGM's paying guests. The Resort's narrow sea front was now vastly wider, thanks to the annexed land.Villagers were externed. An army of labourers watered the lawn using 200,000 litres of groundwater a day, even as Tamil Nadu reeled under a drought.

Drowning the sea's lullaby :

And then the parties began.

While the fishermen were agitating on one layer, other residents aggrieved by noise pollution were on another. We kept hearing tales of MGM having 'full rights' to the land, its political connections, its ruthless ways. We did the simple, the proper and the obvious: trips to the Collector's office, TNPCB and the police requesting something be done to control noise. The noise control unit of TNPCB finally conducted an inspection on Feb 21,2003, found the levels unacceptable and served a notice on MGM Beach Resorts.

Far from being chastened, MGM's violations grew more blatant. Residents were driven out of their peace to form, in early 2003, the East Coast Citizens Organisation [ECCO] with me as President and Navaz as Secretary. Some 50 people joined as members. I knew from publishing GoodNewsIndia, the power of Internet and so ECCO got a site too.

On July 12, 2003, John Exshaw, a liquor brand set up bars on the refurbished temple lands to host a party - a more ironic use for a once sacred grove is difficult to imagine. We went to bed at 2.00 am, after failing to get the police to stop the deafening noise. Then followed a series of parties without break for the next year.

On July 30,2004 a bumper ad appeared for a similar liquor party. The same day Navaz and I waited a couple of hours at the Secretariat and met the Home Secretary. She had headed the TNPCB before, remembered us and was annoyed by the violations implied in the ad. She directed us to the Deputy Inspector General[DIG] who suggested we meet the Superintendent of Police [SP]. We went as a delegation of about 12 residents and the SP said that while he could not cancel the party he would ensure it disturbed no one and ended early.

What in fact happened on July 31, 2004 needs to be told in some detail.

The play begins:

The cast of players is almost complete. What happened next in the play? "Ferrer is one of the least recognised men in India," says Bablu, now."His role in evolving development strategies was path breaking." But twenty years ago they were impatient with his prescriptions. Ferrer believed in technical and management solutions: tube wells, women's organisations, efficiencies etc.

It takes a very long time to work with people who may not know how to articulate what they want, but who certainly know what they don't. Despite great stresses in her personal life, Mary's hard work in Nalgonda was bearing fruits. But the YIP was not going anywhere. Work put in seemed to amount to nothing. Were they on the right road?

That's when Ram Esteves happened. An intense, serious man, he brought Marx over as a solution. In a course that ran 3 months he taught 'dialectical materialism': set conflicts in motion and out of their interaction, solutions will be born. Marx Study Circles sprang up everywhere. Mary and Bablu met at one of them. Bablu and Narendar were transformed men by now. Mary too was. They had all 'got' Marx. They would seed local revolutions and realise rapid, total development.

For the next ten years, they travelled the district threadbare. They raised awareness among marginal farmers and organised them into effective unions, in order to leverage their struggle for rights. Today, the Agricultural Labourers Union they initiated has over 200,000 members all over AP. But that is another story. Mary and Bablu and a close associate John D'Souza believed they had to go beyond unionising farm workers. D'Souza is a pioneer in the field of development whose work stretches back to 1972. He is today the Executive Director of Centre for Education and Documentation, Mumbai, a fine institution serving development work.

Driven to Gandhi:

"One day, a long-known fact popped up again, but with a new and greater compulsion," says Bablu. Rayalaseema ["Royal Realm"] was in living memory, a wooded country. Streams flowed everywhere. There were numerous reserved water bodies across the country. Penukonda, now a bald, burning hill, was then known as a balmy hill station where the king had his summer retreat.

Environmental vandalism of the last six decades had disrupted ancient work cycles of the countryside. Villages had been shell-shocked by the discontinuity. They were too wise to know that the prosperity that YIP promised cannot be grabbed from someone else but had to rebuilt. They needed new maps to rediscover their disrupted connection with nature.

"It occurred to me then, that we were not part of the productive processes but were standing apart, preaching revolution to preoccupied villagers," says Bablu. Then he adds softly: "Marxism is a great analytical tool. But it breeds arrogance and closes your mind."

Gandhi was wiser. Even as he carried on his political work, on another plane, he strove to understand the salt of the earth. Gandhi went beyond drilling deep wells or organising the masses for revolution. He believed in life that was aligned with nature, not in a struggle against it

A cloth merchant donated textile for 500 sets of uniforms. They began to collect partly used stationery. The rest of the requisitioned items had to be bought. Pawar took a loan for Rs.15,000. Let us pause a moment, to applaud a clerk who borrowed to give- and so founded a mission. They hired a van and travelled for a week to rural schools in Lanja taluka. There at simple meetings, they distributed their collection. And returned home fulfilled.

That pattern has barely changed in the last 15 years, though everything has grown and become organised. Within three years, what began in Lanja taluka, extended to Sangameshwar and Rajapur talukas. They began to communicate through advertisements in local papers as the response grew steadily. In 1994, the Lanja Rajapur Sanghameshwar Taluka Utkarsha Mandal was formed as a charitable trust. Today with some 50 busy, salaried clerks as members, the Trust runs an operation spanning 3 counties, hundreds of schools and children, calling for an average annual budget between Rs 500,000 and Rs 900,000.

Regular as the monsoons :

The Mandal's two main activities are to provide materials and supplies to schools and children, and to find sponsors willing to adopt promising children's continued education. The exercise begins a couple of months before every monsoon. In March-April headmasters respond to the Mandal's advertisements in their local dailies and send in their requisitions- mostly stationery, basic furniture, clothing, shoes, school bags etc. Unspeakably, saddeningly, trivially priced for most of us, but unaffordable for thousands of rural children.

After sifting through hundreds of responses, members prepare a master shopping list. It's a rule they have that only the best will do; no cheap goods just because the children are poor and in the countryside. They shop for best value deals.

The Mandal began its adoption programme in 1996. Under it, promising students are selected based on their needs, diligence and potential to benefit from the programme. Teachers and headmasters endorse applicants and during annual visits, Mandal members personally interview short listed candidates. Detailed files are prepared on each and sent to donors.

Mandal's criteria for selection and terms of offer, are noteworthy. The application form asks for no details of caste or religion. What they ask in return for support, is that the student maintains a minimum of 90% attendance and passes all exams every term; there is no pressure to top the class or score high.

They decided to focus on five small doable areas. They also distinguished between mutual corruption and extortionist corruption. "When two people agree and indulge in give and take corruption it is very difficult to fight it. On the other hand, most people are routinely extorted for small, important services like getting the refunds that are their due, getting a PAN number allotted, getting authorities to act on appeals won etc. We decided to begin here."

From left: Suchi, Manish Sisodia, Santosh, Ritu, Rajesh [behind Ritu], Arvind and Rajiv.

With Kejriwal prompting from the wings, a Parivartan team called on the Chief Commissioner of Income Tax. They presented a couple of simple suggestions to bring in transparency: for each application for a service, let there be a serial number, let applications be processed only in a strict queue and let the queue be published. In other words, remove the power of random picking. The Commissioner seemed open to the suggestions. Parivartan then publicised all over Delhi asking citizens not to pay bribes but to approach Parivartan with their applications which will be processed transparently in a queue. They collected 400 such applications and went back to the Commissioner.

The fight in the corridors:

They found he had turned hostile. He berated them for putting up banners and slogans that implied that his department was corrupt. He then asked the Parivartan team to leave. They did, but not to disappear. Instead, they petitioned the Public Accounts Committee, the Vigilance Commissioner and Manmohan Singh, a politician of renowned honesty. Under pressure, the department cleared the 400 applications- and promptly went back to its old ways.

Ram Krishnan is an alumnus of Indian Institute of Technology [IIT] Chennai. Visiting it on one of his annual trips to India, Ram found a list of ironies. IITs are leaders in producing cutting edge technologists. In IIT-Chennai there are 3000 students in 12 hostels named after India's famed rivers. The campus is on 640 acres of wooded land. Yet the institution had to close two months extra recently because water ran out. Following some advocacy by Ram, hostels got steadily rigged for RWH and the water supplies now last longer without having to buy in. Read the full story here

Another Chennai man who is taking the RWH mission seriously is K R Gopinath, an engineer - businessman. His house is something of a RWH perfection. He has also taken the idea to industries in and around Chennai. Many of the TVS group industries, Wimco, Stahl, BEL, Godrej and Boyce -it's growing list- have installed RWH schemes.

Rejuvenated memories:

There had been older, passive, no-cost methods of harvesting rain water. Once there had been ponds in most villages that supplied drinking water. But just as much of urban India has suffered a disconnection between milk and cows' udders, the laudable objective of Rajiv Gandhi Drinking Water Mission for rural India has caused a disconnection between water-supply and ponds. The Mission has taken away personal responsibility for water management and made its supply, the duty of panchayats and block development Officers.

Bore-wells will deliver water, just as plastic pouches deliver milk, was the emerging belief. As a result, these ponds ['oorani' in Tamil] have been neglected and silted over. Ram Krishnan, decided to revive an oorani in Vilathikulam in Thoothukkudi district. He found a thoroughly professional partner in Dhan Foundation in Madurai to help him design the project and a small local group Vidiyal Trust to implement it. Dhan had pioneered what is becoming known as the Edaiyur model, after the first village that revived and modernised an oorani. People, the village panchayat, the government, a guide [eg Dhan] and a donor are all involved. Everyone contributes. In Vilathikulam, the official piped water is unreliable, but the dredged and dressed up oorani, has revived pride and sense of security. Pumps and pipes are still used but the water source is not some bore-well but the visible oorani. [Download a beautifully illustrated report]

Gandhi is not sufficiently remembered for his crusades on Bhangis' behalf. At the 1901 Calcutta Congress Convention he shocked delegates asking them not to engage scavengers but to clean their own toilets. Finding no takers, he shocked them some more by dramatically cleaning his own. It left a deep impression on the convention. Subsequent annual conventions had only Congress volunteers cleaning toilets. Never lived a man more fit to utter, "Be the change you want to see around you."

Apprenticeship among scavengers:

At Das's urging, Pathak went to live in a Bhangi colony in Bettiah. The three months there were a revelation: people who cleaned others' toilet did not care to keep their own, clean. They had accepted that they were a condemned lot.

There was time on Pathak's hands to ponder a solution.The only solution was to make toilets maintenance-free and re-train the scavenger caste for other occupations. The western-style flush toilet and centralised water-borne sewage system was too unaffordable for India. Gandhi popped up in view again. He had coined a slogan: 'tatti par mitti' [soil over shit]—he was saying 'compost it!'. He would dig a pit, put a toilet pan over it, cover it with soil when it filled and dig a new one. Several Gandhi followers practiced the simple system [See last para at this page].

In a book that Pathak treasures till today, the World Health Organisation [WHO], many years after Gandhi and after much research with all toilet available solutions, said "out of heterogenous mass of latrine designs, the pit privy emerges as the most universally applicable type." It was low-cost, needed little water, did not pollute [-it in fact turned waste into resource], offered privacy, could be built quickly, locally, and most all needed no scavengers to maintain. So here was an answer.

Not so Sulabh [-easy]:

Meanwhile, the Gandhi Centenary Year had ended, but Chief Minister of Bihar, Daroga Prasad Rai wanted the sanitation cell to be spun-off and institutionalised. Sulabh Sauchalya Sansthan [Simple Toilet Institution] was formed in 1970. R L Das was President, and Pathak its Secretary. Then the roller coaster rides began again. There was no money for Sulabh. D P Rai government collapsed. Successors were not as keen. Grants were approved but never materialised. IAS officers promised much but were transferred and gone, before they could deliver. Even a letter coaxed out of Indira Gandhi by Pathak to Chief Minister Kedar Pandey, took them nowhere. Exactly the set of circumstances we would list as reasons for not being involved in India; but Pathak's obsession with scavenger eradication made him hang in there.

Damu noted a strange fact when he went around Bangalore. There were children at work everywhere and a majority of them were from his reasonably prosperous, educated home district of Udupi. Famous for its cuisine and entrepreneurs, children were encouraged to fan out and work in 'Udupi Hotels' that dot India. Damu realised his work was in Udupi district, which he had left looking for a career. He went back in 1989.

Being the temple priest's son gave him credibility. The man who was organising factory workers, began to organise children. He reached out to working children planning to leave for the city. Most were slaving away as cafe labourers, cleaning and washing. He got a small group together and they called themselves the Bhima Sangha, after Bhim, one of the legendary Pandava brothers.

Why Bhim? Children spoke with great sensitivity: "Bhim was the most selfless of the brothers and was always taken for granted. He willingly laboured for the family despite neglect and ridicule." They also chose the elephant as their symbol--for strength.

Beating the UN:

The idea was to give children choices in vocations, that would lead them to self-supporting careers. Damu says, "Poverty is not just economic as many believe. The worst form of it is the poverty of information that children are subject to." Damu began to create a series of courses that would lead to self-employment: carpentry, masonry, basketry, horticulture, mechanical and electrical trade work, welding, driving and many others. They are housed in a residential campus in Basroor --called Namma Bhumi or Our Land-- for the period of their training. While there, they are also humanised and empowered with arts, theatre work, music and debating skills. Nandana goes about raising funds and raising awareness leaving Damu to work closely with children.

In 1990, CWC declared April 30th as the Child Labour Day. Thus the concept of a day in an year dedicated to issues of working children originated in India. Why April 30? Because the child worker must be cared for ahead of the adult one, who has the May Day. It was to be another 12 years before the UN's International Labour Organisation nominated June 12th as the World Day Against Child Labour.

In 1987, he met Dr Khilnani who cured him of stones in the kidney using homeopathy. Struck by its cost effectiveness, Dada used his Trust funds to start the Hari Om Free Clinic in an apartment he owns. He doesn't stay there though- he lives with his nephew, as a member of the extended Lakhiani family.

'Free' should mean free:

Three visiting homeopathy doctors -who are paid small honorariums- visit it in turns daily between 9 and 11 am. He won't accept any payment, not even voluntary donation. "Free means free". He says the modest corpus is more than enough for the purpose.

"Oh, he is amazing", says Dr.Mansur, the only male homeopathic doctor out of the three who work here. "He is very knowledgeable; brings in promptly the medicines we ask for. He knows the ones tried before, all about potencies and so on. It feels good to be able to come to this free clinic once a week and treat people". Dr.Urvi Vakharia, who comes in twice a week says, "I have worked in some other clinics, but there is no proper handling of records, medicines are not available; but here, it is very ordered, which I think is because of Dadaji here. He's extremely fastidious".

Sometime in the seventies, the redoubtable Master Jethanand resurfaced in Agra, with no bombs in his thoughts. He was now the manager of the 250 bed Sundarani Charitable Eye Hospital. The old mates met every year, until the Master passed away a few years ago. Dada deputed at his bidding, a nephew to take active part in the hospital's activities.

A day in the life of:

Dada keeps on going, maintaining a punishing pace. His day begins at 5 am. Following a walk, he opens the doors of the clinic, tidies up, brings out the trays of medicine bottles from the cupboards, arranges chairs and adjusts an awry picture or two on the wall. He is present till the doctor leaves, puts away the things and then locks up.

After a quick lunch, he takes a crowded train to Churchgate and from there walks the 2 km to his office at Gunbore Street. He pores over details of management and accounts. He returns home at 7 pm. He has no car. Every Saturday, he takes the train to Prince's Street in Marine Lines to replenish homeopathic supplies.

They next began to organise them into self-help groups or 'sanghas'. Eventually there were 154 sanghas with membership between 15 and 20 each. The sanghas formed a federation and began to elect office bearers. Sanghas were encouraged to be just talking shops, because the team knew that it always led to bonding. Sanghas discussed and evaluated all ideas the BAIF team proposed. It was soon agreed that without concord nothing could be achieved.

A spectacular demonstration of this bonding came in 1999. 525 people from all the 22 villages gathered at Harogeri and built a check dam. It is 140 feet long and 12 feet high and can arrest and recharge 2 million litres of water. It took them 3 months to build, using only locally found materials. But the most amazing thing about this dam is that only 15 farmers directly benefit by their proximity. Villagers didn't mind that. They understood that water charged into the ground benefited everyone. The message that water was central to development had gone home.

Ponds arrive:

You can't talk to a BAIF man for long before he will wax eloquent about farm ponds. The success of Tiptur ponds has been widely acclaimed. Ponds therefore, began to crop up at Dharwad as well. The only cash that was ever given to the beneficiaries was between Rs.3,000 and Rs 10,000 per family, to either dig a pond or start a small business, if landless. This too was a loan, paid back with interest to the sangha's coffers.

Eventually 740 ponds were dug, each with a capacity of 140,000 litres. In all 100 million litres of water began to be trapped and charged into the ground every year. The difference was there for all to see. Water levels rose in wells everywhere, soil began to be wetter, fodder became available for longer periods and top-soil run off ceased. Drought was on the back foot.

Families were encouraged to plant fruit trees and other trees of economic value. Medicinal plants and fodder crops were grown. BAIF issued saplings of assured quality. Food basket on the table began to be diverse and rich. Moods began to lift.

"I planted only what I found in the neighbourhood. Mango, jack, pepper, pineapple, silk cotton, banana, coconut, cashew and vegetable species. I picked the best of a breed and brought it over. In a few years, water stayed for longer months in the ditch. The land got cooler and the soil felt wetter. The leaf pile was getting thicker.

Message on a straw:

"One morning, I stopped in my tracks. A sturdy plant of rice, ripe with grains stood in my way. How had I missed it all these days? Where had it come from? Where it stood was no wetter than other parts of the farm and my land was by means abundant in water. I had certainly, not planted it. It was unlike any paddy I had known. It had buxom grains on 16 strands, all on one stem. It stood alone glistening in the morning sun.

"I was overwhelmed. I took it home and shook it. There was close to a kilo of grains from that one plant! And so began my rice harvest year after year. I scattered the seeds on unploughed land, spread leaves and manure and watered it by hand. There was no attempt at flooding the patch. Slowly, the patch grew wider but it was never more than a tenth of an acre. All it called for was one man's labour for three days in a season. That was enough to feed our family of five continually, for forty years.

"Folks were surprised. Paddy in dry land? Without flooding? Papers wrote about it. I was told that a Japanese man called Masanobu Fukuoka had done something similar. There was a stream of visitors asking questions. I was called to meetings, seminars and was honoured by adoring audiences.

More pay-offs:

"What cash I required, I got by growing vegetables in 20 cents and from what my trees gave me. We ate what we grew. I milled the silk cotton seeds for oil for our lamps. I deepened the ditch, and built a lined well over it. I drew all the water by hand, for the land and our home-- about forty pitchers in a day. There has been no electricity on this land till two years ago. Not that power-lines didn't run in these parts, but I didn't want it. Children went to school and read by oil lamps.

"My first son was a good student. When he passed high school, Mr Haridas Bhatt, principal of MGM College in Udupi, who was my admirer took him in at no cost to me. When he graduated, Mr K K Pai, another admirer, took him into his Syndicate Bank. He went away to become a good banker. I was happy, for him. I got my daughter married to a good man. The land had helped me do my duty by her. But I was happiest when my second son Ananda, came home from school one day and said: "Father, I do not want to study any more. I don't understand anything at school. I want to work with you on this land." He has been with me and does most of the hard work. I think he made a great choice.

"I don't want you to think I am a poor man in money terms, either. My bank account is as rich as this land. And it grew without any clever skills. I have more than what many salaried people have at the end of long careers. The term, 'impoverished farmer' bothers me.

As we study the many strands of the China story, it is inevitable references to India's events and experiences will keep coming up. These are juxtaposed only to present the contrast. Preferring one road to prosperity over another is a personal choice every Indian has the privilege to make. He *must* make that choice though, for, without convictions, no action is effective. GoodnewsIndia too will state its choice, after listing how India and China differ.

The Contrasts Catalogue:

Period and poverty:To begin with, China has been at true-blue capitalism, for a longer time—25 years—than India's 13. During the 13 years of India's unsteady experiments with the liberalisation process, poverty has fallen from 46% to 23%. For the last 25 years, which is an identical period of comparison, the fall has been from 55% to 23%[Reference]. These figures show that the rate of fall of poverty in India was faster paced in its open-door period, than in China.

Now, most incredibly, Guardian says, China defines its poverty line at $76 per year, whereas India conforms to the World Bank norm of $365/year. Think that over deeply and then, evaluate India's performance. Also, for a country with an average income of $1000 a year, China's definition of its poverty line is astounding. Only less so, than world's applause for its performance.

Health of the economy: Nor is poverty definition, a rare case of China's non-conformity with accepted units of measure.Dr Subramaniam Swamy says, "... China's compliance with the UN Statistical System is partial whereas India's is total". Truth is, China's is an 'open' economy in a 'closed' society where 'facts' are opaque and answerability is non-existent.

It is widely suspected, that a large part of it's huge FDI is in fact, ill-gotten local money [—'black money', you'd call it here] round-tripping back as investment. What's worse, China uses that capital way more inefficiently than India does, say economists Sachs and Porter.

In contrast to India, where economists, the business press, investors, regulators and the stock-exchanges routinely dig out wrong-doing, discuss and force corrections on its financial system, in China, all is still. There are barely defined norms for grant and collection of loans. Rambunctious entrepreneurs—who'd amaze even Indians, rendered cynical by their merchant class—have scattered huge bad debts on the way to building the China-showcase. Gordon Chang in 2001, laid out a 5 year time-line by which, China should now be convulsing in the open as an economy is distress. Many thought his was, too dire a prediction. The Chang prophesy hasn't arrived as yet. But who knows? The rate of growth of China's economy is slowing down and its competitiveness is fraying.

Up goes a wall and down comes another:

JK's dream of extending the greening programme beyond the campus inched a little further in 1980 when the Andhra Pradesh government ceded to the School's care, some 150 acres on the south hills. For years the School had been trying to regenerate these hills. But recurring droughts combined with penury of villagers had dashed all efforts. Deliberately set scrub fire was a routine myopic practice to encourage quick fodder soon as the first rains fell. Constant grazing gave no opportunity for the regeneration process.

The redoubtable Naidu proposed he would build a stone wall to fence off the 150 acres. It was an outrageously daunting project fraught with social tensions. Villagers resented it. But Naidu was upto the task. It took him over a year but he did it. He is a big made man who has just turned seventy. He is a YMCA-trained fitness coach and loves the outdoors. He rallied the students and they participated in great numbers. One can get an idea of what the hills looked like in the 1980s from the background in this picture.

The wall itself is made of locally found rocks stacked with care but without any mortar [Picture]. But it snakes over 2.5 kilometres of undulating ground, up hill and down slope![Picture] And it has made all the difference. Naidu and the students have also, over the years, intervened in about 6000 places digging tiny ponds, building bunds, plugging run-offs, creating recharge trenches and of course, planting ceaselessly. They planted over 20,000 saplings every year and continue to do so. In the summer they form bucket-brigades to water the stressed plants. Nature as always responded handsomely[ Picture 1 ] , [ Picture 2 ]

Social tensions that the wall had caused were resolved once and for all, ironically because of the drought itself. By the mid eighties, when the whole region was parched, the walled south hills produced abundant fodder. Simply because the wall had foiled grazing. The School generously allowed the villagers to harvest all the fodder they wanted. As heavily laden bullock carts creaked off the hills, they were beyond the turning point. Villagers learnt lessons in sustainability: if nature is left alone and given a chance, it makes do with whatever rains that come by and roars back with abundance.

"The state may not be evil, but it's a wily adversary once its mind goes into a dumb spell. It's machinery will seduce, split, buy and overwhelm vulnerable people," she says. "The once cash-poor Santals were suddenly into money. Their drinking used to be communal and built into their culture. Now they had the money to drink without reason or occasion, and at any time. They were willing to turn their backs on a great heritage and give up their lands. The government had its dam. The hills and the dales we had traversed for year was gone." She was shattered. There was a broad sheet of water like a shroud over a culture. The rebel's voice went weak: "was it futile to stand up for what seems right?" She began to fall ill.

Elsewhere, Fr. Gregory D'Costa's doubts were rearing their heads. The church had indulged him and let him explore. He spent some time with Fr Anthony D'Mello at his Sadhana Institute in Lonavla near Bombay. Fr D'Mello was indeed a radical priest. But his work also defined the limits of working within the church. Greg's learning said he was blinding himself to the world that lay beyond the life he had chosen. He went away for a year to work on watershed development in Maharashtra. And became more convinced that he must begin anew if he were to express himself. He considered the possibility of giving up priesthood. "I had no quarrel with the Church or Christianity," says Greg. "I still don't have. My problem was, I had no quarrels with other religions and systems either. It therefore seemed so pointless to brand myself." He was close to a major decision.

Redefinition:

Bernie was recuperating in her brother's house in Surat when Greg dropped by one day. She had heard of him as a brother's friend who went away to become a priest. Now she met him in one of those contexts that life routinely arranges for us. They began to talk of their worlds.

As Greg heard Bernie's story of a penniless life among the Santals, it hit him: "I already feel a failure for not knowing my mission; she knew her's, and failed-- but only after having fought. Here I am in reasonable physical comfort, a man who had taken a vow of poverty. There lies Bernie who, without any vows, had unconsciously chosen selflessness in the cause of injustice." Greg was convinced his decision to leave was right. It shook his admirers in the church.

In well documented experiments, Garthe co-fired these nuggets in boilers along with coal, at very high temperatures to generate heat for farmers' horticultural greenhouses.

He writes: "Combustion tests were conducted in 2002 at Penn State's Energy Institute. Discarded, soiled watermelon mulch film and drip irrigation tape from farms in California, Florida and Pennsylvania were made into fuel nuggets, then co-fired with coal in five and 10 percent quantities based on heat value. All testing conformed to US Environmental Protection Agency [EPA] standards.

"Regarding emissions, most of the tests conducted revealed that plastics indeed burn well with coal. Research on plastic-coal mixes has been done elsewhere in years past with good results. The presence of coal in the mix helps maintain the temperature of combustion around 1800-2200 degF, minimizing most emissions of concern. However, in the stoker simulator some of the samples were quite soiled, Florida in particular with sand, thus test results for dioxin emissions passed, but were disappointing. It is believed that the high ash content may have restricted air movement through the burn. The combustion team plans to continue testing in a full-scale unit soon to assure that emissions are in conformance with strict guidelines established by the US EPA."

Since then, interest in Plastofuel has grown. A South Korean firm has fabricated a burner that will combust Plastofuel directly, without any need to be mixed with coal. Patents have been filed for the process and research continues. Garthe says, nuggets maybe made in backyards or the production can be scaled up to industrial strength plants.

Markets for Plastofuel:

Sizable markets are emerging for Plastofuel and other plastic derived fuels [PDF]. Cement and steel majors are conducting trials using plastic waste as fuel adjunct, with a view to reduce energy costs. Cement giant LaFarge North America, Pa has begun trial burning waste plastic as a fuel supplement. These trials are being conducted with a close eye on emissions. The company is keeping local people informed and involved.

'It's no disease, so there's no cure':

The three undertook the special educator's course at KPAMRC. When they met in 1995 to start Shristi, they had 26 years of work experience between them... and nary a penny. Sometimes it helps to be money-unwise, and clue-less about costs, as many of the GoodNewsIndia heroes featured at this site are. They seem to have an unconscious faith that in this country, good causes will find the support they need.

They rented a small house in Basaveshwara Nagara in Bangalore and put up a sign. Soon, businessman Bipin Avalani drove up and handed his son Hemal over. Hemal, then 16, could not even clean himself and needed constant attention at home. The girls had their first ward. Bipin gave them Rs.5000.

Shristi fanned out to schools nearby to spot children needing their care. What they saw would move even the hard hearted. There was no programme to sort the children and grade their needs. They were often mocked and treated as though they were insane. Some of the hyperactive were even tied to chairs. Thirty years ago, for a struggling India, the needs of non-ordinary people was a peripheral issue.

The central difference in special people is their difficulties in communicating, associating and comprehending a world we, the 'normal' have constructed. Within that difference, there is a whole range to the difficulty; from the marginal to the extreme. Autism is a catch-all phrase to a wide spectrum of disorders. It has in fact been called the Spectrum Disorder.

It is a lifelong predicament. Since it is not a disease, it cannot be 'cured'. But most, can be trained to care for themselves. Autists are often very creative and compassionate. They respond to music, colours, dance and being given small responsibilities. The trick is to find what a child is good at, for it is certainly good at something.

'Just in time' help:

Bipin Avalani's Rs.5000 had seemed like a windfall to Shristi's founders. After all, throughout their earlier work-life of 23 years between them, they had seldom earned more than Rs.800 per month. But reality caught up with them soon, as more and more parents brought their children over. Driven by bills, the young ladies borrowed Rs.35,000 from loan-sharks at 36% per annum!

Such astounding naievete seems tolerable in do-gooders-- in India, the parachute always opens on time. Meena who spends most of her time raising funds says: "The parents made sure we didn't fold up. They gave what they could and brought their friends over and they gave generously too." Today, 6 year-old Shristi cares for 70 special people. The monthly budget has grown to just over Rs.200,000. While that's a number that Meena must vault every month, Rs.80,000 of it comes from patrons and parents.

In 2002, Shristi created a happy modern facility at Chennanahalli near Bangalore. Their services are now available to rural parents as well. The 2 acre land on which this centre stands, belonged to Mrs. Jayashree Prasad -- she donated it Shristi. K Venkateshwar facilitated its acquisition in several ways. Mrs.Saroja Naidu, a legendary philanthropist of Bangalore gave Rs.400,000, Amar Rehman from Chennai gave Rs.50,000 and many others send regular sums.

Now to garbage:

There is some concern now that his business model is stoking greed and quick grabbers are moving in. Fuad is worried that the idea of cost free, public sanitation may lose out if cronyism creeps into city administration. There are now about 80 toilets based on the Fuad model. He hopes all would pay attention to upkeep. But there is a built-in safeguard in the idea he has pioneered: if a toilet is run down, it won't attract advertisers.

Fuad is now attempting to make garbage pay. He has built collection and sorting centres where again advertising will pay for the process. He admits it's not a commercial success yet. And he has begun to ponder what else he should be doing to improve India's image in terms of public sanitation. So the question arises, what about toilets for the poor and for small towns? This questions has been asked in the past and almost always been answered wrongly. Tokenism has ruled and subsidies and handouts have steadily been siphoned off. In the end the poor get unusable toilets.

Fuad says, let entrepreneurs in and they will create the right commercial product. Has not C K Prahlad, the management guru said that Indian entrepreneurs are ignoring the huge market of the poor that exists in India? Bottom up planning is good when you are talking of livelihoods. When it comes to behavioural changes, the process is always from top to down. Given TV, travel and visible changes in the cities, the poor --whether or not you like it-- wish to ape the rich. Computers, education, mobile phones, grooming, and lifestyles are being mimicked. Why not toilet habits?

So how do you build toilets for slums and small towns without subsidies? Fuad has a brilliant idea: build quality spaces but to offset for the fact that premium advertising may not be forthcoming, run a shop attached to the toilet! He is yet to try out but is sure it will work. It would need of course new thinking on the part of local governments.

Because also, the government too has been supportive: it teamed with the Confederation of Indian Industry [CII] to form the India Brand Equity Fund in 1996. Its mission? "If India.Inc is ever to rival the vaunted Japan.Inc, it has to get its homework right and only then will any publicity ring true." There is increasing evidence the labours are paying off. India today is the greatest market for quality gurus, management consultants and deal seekers. It is even a high end job market: many Indian firms --eg. Jet Airways, Ranbaxy-- are hiring Westerners.

Manufacturing had nearly been surrendered to China by prominent minds that ought to have been wiser. Today, about five years after China-scare-times, Indian manufacturing is alive and growing. As a supplier of quality parts to the global auto industry, India is becoming the rival to beat. Part of the reason of course is West's experience in India. Mercedes Benz says its India plant is its best outside Germany. Raymond Spencer, founder of Kanbay says, "India is a knowledge center. It is not a cheap labor pool. It's not a factory. It's a knowledge solutions center." It is that mindPlus labour that makes Bharat Forge, the feared competitor in the forged parts market; that makes auto-grade steel from Tata accepted overseas; that makes tens of little known 'wholly Indian' auto parts companies carve out markets.

The values in the chain:

In terms of food and beverages, it would be no news that the likes of curry, basmati rice and tandoori chicken are established favourites. But did you know that the Dabur's Chyawanprash, Hajmola and Boro Glow are becoming popular. Or that Kingfisher is a leader among beers? And wonder of wonders, in just under a decade since it began, Indian wine industry is placing its bottles on tables abroad. Stanford educated Rajeev Samant has almost single handedly created a niche for Indian wines abroad. Albeit the volume is small, his Sula wines are exported to Italy and California.

The wine story is a classic illustration of how the value chain works. Grapes grown in Maharashtra was 'commodity' when it was table fruit; now transformed into wine and branded with elegance, profits are flowing down the chain. The farmer at the lower end is connected with the rich spender at the higher end.

But these connections will not work if a country did not have a likeable image. India is going through a favourable re-rating. In a world full of turmoil, India's stoic calm, democracy, hospitality and family values are all being viewed with much admiration. Many societies have lost these and 'progressed' but are strangely restless. India on the hand is old-fashioned and yet 'modern'. It is scarcely doctrinaire. Its music, dance, crafts and religion are open and inclusive. Yoga, ayurveda, meditation etc have a universal appeal. India seems to say that you can be in many worlds at same time.

Manu precipitated the most deafeningly loud "why?". Anuradha rented a hovel and began to care for him. Manu being washed, cared for and loved became a curious novelty. Soon other parents brought their handicapped wards. Coming everyday with Shamika to Giri Nagar taught Anuradha ways to do things without complaining, agonising or imagining enemies. A wealthy friend --who refuses to be named-- bought her a shanty for Rs.70,000 and the Sri Ram Goburdhun Trust had a permanent home. Anuradha's inheritance too began to flow through her work.

Coming back to our enquiry, *why* do Manus happen? Anuradha began to get some answers. They happen because poor adults are without hope and their children will forever remain out of the 'good' jobs loop. Because schooling for the poor, where it does exist, begins with the presumption that they can never be taught the core skills that good jobs need. Shamika's experience, terrible though it was, at least did not include corporal punishment and mockery to which the poor are subject. Anuradha saw Shamika blossoming when once she was filled with responsibility, purpose and optimism. Why then, won't the poor?

Project Why began offering real education to the merely school-going. Available to all is the immensely popular English speaking course. Then with machines donated by friends, a computer centre started at which children clamour for their turn. Today there are over 500 children taught by 35 teachers. Children going to the afternoon schools come to Project Why in the mornings and the morning schoolers come in the afternoon. Attendance is near 100% and enthusiasm for learning bubbles through. Beneficiaries are toddlers to Plus-2 students. Teachers are almost entirely slum raised folks; they need to have passed Class-8 at a minimum, but many are graduates and there is even a Masters. There are about fifteen children with various handicaps, who are ferried in Project Why's three wheeler, washed and fed and taught. The monthly budget of Rs.85,000 goes mostly as handsome teacher salaries --between Rs.1500 and Rs.3000-- and rentals for the five or so shacks that are rented. So Project Why is creating a cadre of slum based teachers, trained to be creative and human.

"We don't realise how much a dysfunctional school system contributes to social discord," says Anuradha. "The formal schools in fact end up convincing children that learning is beyond them. Add to that the abuse, mockery and caning and you have the perfect recipe for future outlaws." She was puzzled in the early days, that students would proffer their text books and ask her to *underline* passages. Then she realised that this was the standard teaching method in their schools: a teacher would underline and her students would memorise those lines. There was no other effort to teach. Even the pathetic pass mark of 33% was a difficult hurdle. Children discovered they had 'failed' as early as age-10. They accepted a life away from the mainstream.

Between running around for funds to construct the Academy buildings Thathachar has remained focused on letting nature rebuild desolated wasteland. When some old houses were being demolished in Melkote town, he discovered the walls were made of rich red earth. His Hallikars ran convoys for days carrying this rich rubble to his rocky estate. The clumps were broken down and spread everywhere. He restored eight lined kalyanis and unlined ponds within the campus. He harvests no more than half the fruits and flowers. "It is the way of the wild. One takes what one needs and lets the rest feed the birds and animals or drop to the ground to rot. Modern farming thinks it is smart to maximise produce and wipe it clean. The ancient way was to live with nature, not treat it as a profit centre," he says.

From land to knowledge:

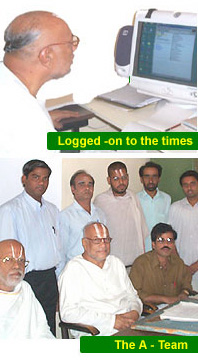

When the handsome centre was eventually built it stood in a micro landscape that approximated to what the ancient texts described. From there he leapt to very modern times. It was a time when desktop computers began to be affordable. Thathachar was quick to scent their importance and relevance to his work. He soon became an adept. "I simply exposed myself to it and realised its potential," he says by way of explaining how he can handle all the gear and understand how programming languages work.

The Academy began to publish authentic English translations of Sri Ramanujar's works as also treatises on Vishishtadvaita. He began to collect works written on palm leaves. He went all over south India and householders happily gave him their heirlooms. "This is what is marvellous about an India not yet gone 'modern'," he says. "In the West people would hand these to Sotheby's for getting the greatest price; the people I met gave them away when I told them I would care for them." He has a collection of over 10,000 palm based texts, 850 rare old paper texts and over 25,000 books -- all related to Sanskrit. A large bowl of lemon grass oil is constantly kept warm amidst the array of shelves. It is enough to effectively preserve the treasures.

The Academy has state of the art facilities for digitisation of vulnerable texts. It has an in-house printing press. Thathachar has gathered a team of Sanskrit scholars from all over India to organise the texts for publication. The Academy also publishes media for popularising Sanskrit learning. There are lexicons and commentaries for students.

With passing time however, it is becoming clear that Sanskrit is just the visible skin over a vast throbbing organism called cosmos. "How silly to think Sanskrit is a language for a ritual or a religion," he says. And then asks: "Tell me how you translate 'gyan'? You'd say knowledge, knowledge system etc and you would still not have captured the spirit of the word. The closest perhaps is, 'right and total knowledge of the cosmos'"

Each pond has two connections with the contour channel. These are lined and act as silt traps. The farmer cleans these and the channels regularly to regain the soil washed down. At the end of the summer the pond is also dredged to recover nutrient rich soil. The contour lines eventually connect to a main drainage line which flows down the valley. This drain has many check-dams to further localise water harvesting.

Manjunathapura first:

The State from time to time allots land for Dalits in ceremonies redolent with media attention and speech-making. These allotments are however far from habitats and unwanted by anyone else because they are hard to farm. There is such a Dalit allotment in each of Karnataka's districts.

Manjunathapura near Tiptur is one such. 68 families had been allotted 100 ha on barren slopes of a hill. Water was available at 200 feet but there was no hope of getting any electricity. Even if it did come, the people were too poor to buy pumps. Since getting the land long ago, these families had lived about 3 kilometres away in a 'colony'. Though landed they were labourers travelling miles for work.

BIRD-K's renowned success in Adihalli-Mylanhalli, is in many ways founded on the experiments at Manjunathapura. Their work there began in 1992. They found a doughty champion in Rathnamma [picture above] and a willing worker in her husband Rame Gowda. Farm ponds, contour channels, wind breaks, biomass accumulation, fruit and fodder trees on bunds, diversified agriculture and animal husbandry were all sewn together.

What did they do for water in the first year? Its a delightfully unique Indian solution: a pack of 10 mules were trained to shuttle between the colony and the hill carrying water bags slung over their backs. These loyal lovelies had no pack driver but they sincerely ran many convoys in a day. Trees were thus hand watered and nursed.

Results began to show in the second year. Soil moisture and micro climate changes increased productivity. Rame Gowde and Rathnamma's holding became an oft quoted success story. Water table has risen. More and more families have begun to care for their holdings. Some have even moved home. Few go out looking for work. Their farms are productive enough. And finally, these risk taking poor people gave BIRD-K an opportunity to prove its theories and to gain confidence to scale its work to a larger canvas.

Where are those great Indians, the mules that built Manjunathapura? "Oh, they are in great demand. They have moved to another project site, ferrying water!"

And BIRD-K is flying powered by the success of Manjunathapura.

By 1997, all 330 ponds had been dug and connected. Farmers anxiously waited for the next rains. When it came and went, not much change was discernible. There were glum peasant faces all around. Yet the following year changes were dramatic. Soil moisture increased, water levels in the wells rose, water stayed longer in ponds and crop yields got better. What had happened between the first two years? A closer look at water mechanics will give us the answer. When water descends down a section that has been dry for several years, it first wets the grains along the porous path down which it flows. Most of the early charge is absorbed in this process. In subsequent years, the wetting process is completed and the voids begin to fill. As saturation is approached, water rises in wells. Down in the valley rivulets form and flow.

Starting 1998, all these have occurred in Adihalli-Mylanhalli. First the levels in dug out wells rose. And then in 2000, the barren bore wells that we saw earlier spouted like natural geysers, without need of any pumps. The sump in the valley is a vast lake now and has enough water right through the summer. It is estimated that 150 million litres of water is harvested every year. But increased water table is only the obvious effect. The side effects are dizzier.

This is India at its best. Take a pause and review the story so far. We see no struggle, no acrimony, no blaming. The state cannot wire electricity to India's inaccessible terrains. [Most countries in the world don't, either.] So a problem remains unsolved. Then an academic brings his knowledge to bear on it. Dedicated bureaucrats seek him out. At least in AP and quite a few other states politicians back the civil servants. State's funds are made available. People are shown how they can do it themselves. India's hardy folk take it from there. And soon as they get a break, they urge their children to learning. From where then, comes the urge to portray this social system as venal and moribund? Unless of course, it is from the compulsions of a commerce to fill newsprint and airtime.

Within days of Chalbardi being electrified, villages within miles were --in a manner speaking-- electrified too: they wanted their own power plants. In the months since mid- 2001, 10 forest villages in Adilabad have followed the Chalbardi model. The SuTRA team is deeply involved in disseminating the idea of SVO as fuel alternatives. It is working with people and learning from them. It has near enough perfected a standard format. Here is the pattern, give or take a few details. The gensets are uniformly 7.5 kva of Kirloskar make with an eye on standardisation. Power is supplied for three hours after dusk. Each household pays Rs.5 per month [--that is about $ 0.10 !] plus, 300 kg per year of shelled Pongamia seeds. These seeds they gather from the forest floor, bring home, shell and deliver, the while committed to the sustainability of their forest world. The power plant is run profitably with the sale of excess oil and all of the oil cake. Mr N. Sridhar IAS, the current ITDA project officer in Utnoor is a great enthusiast for the idea taking it further down the road.

New leaders, technicians and jobs have sprung up. In the village of Powerguda the formidable Ms. Subhadra Bai leads a women's self help group [SHG] that runs a no-nonsense oil mill business. Gatherers are paid Rs.5/ kg of shelled seeds. The SHG mills and markets 3000 litres per month at Rs.20 per litre. There is a huge waiting list and people come from far. Five more expellers have come up. Govinda Rao is a wandering minstrel spreading word of the SVO miracle. Young lads have become adept at repairing and maintaining all equipment. Children are going up the learning curve. The Ghonds have begun to look at their ancient habitat with renewed love.

Raising money:

FoSS and Anil Gupta's GIAN parted ways here. FoSS had decided to look for ideas outside the GIAN stable as well. They have gone about constructing a robust framework under the banner Aavishkaar, meaning 'innovation'. At the fund raising level is Aavishkaar International [AI] based in Singapore. Dr V Anantha Nageswaran a senior executive with Credit Suisse and Mr Arun Diaz, head of Reuters Consulting are two of its many activists. AI gathers capital from people who believe in India's potential and want to invest in support. There is a minimum level of Rs. 500,000 for one directly investing in into AIMVCF. There is no such limit for investing in foreign currency into AI, Singapore. They have so far raised over Rs.20 million. Their target is Rs. 50 million.

Dr. Krithi Ramamritham, a member of the board [--and Computer Science Professor at the Kanwal Rekhi School of IT at IIT, Powai] has invested not only because it's a good cause but also good business. He, Nageswaran, Diaz, Meehan and Singh have contributed 18% of the corpus. So they have put their money where their hearts are. Nageswran says,"the interesting thing about the investor list is that there are two Swiss economists, two Singaporeans [Chinese], one French and one Englishman." It would seem a lot of people around the world would bet on the Indian mind.

Aavishkaar hopes many more would come on board and make it a big India wide movement. They wish to make it more than a money thing. For example, they wish to create a Mentor Corps made of committed professionals in India who are willing to volunteer their time, experience and skills to entrepreneurs that AIMVCF picks.

AI's funds are invested in Aavishkaar India Micro venture Capital Fund [AIMVCF]. AI's investment in AIMVCF was approved by the Foreign Investment Promotion Board [FIPB] within five weeks solely on the strength of the investment idea. FIPB approval means that both capital and returns made by AIMVCF are freely repatriable to AI. AIMVCF is headed by Mr. Vineet Rai who had, in fact, worked for GIAN. He provides the continuity.

AIMVCF is organised as a Trust and is an approved venture fund under the venture capital regulations of the Securities Exchange Board of India. They are focusing on the west and south of India to begin with.

Elango threw his hat in and won. But despite his long term commitment to the village and work with harmonising it, he found the margin of victory disappointing. But he understood the powers at his disposal. He rolled up his sleeves. His objectives were two: create jobs and bring in hope.

He did not know his Gandhi formally, but seemed in accord. He would build drains in the poorer ghettos and show them the difference. At the outskirts of the village was a factory that polished granite slabs. It had a huge disposal problem with its random off cuts. It was willing to pay for it to be carried away. Engineer,President Elango was delighted. He employed local labour, and built a drain which had smooth granite mosaic walls. The 'colony' drained fast down the slick 2 km long works. Of the budgeted Rs.15 Lakhs for this project Elango had spent just Rs. 4L, half of which went in wages for local folks. But, the specification was to build the drain with rubble stones from a nearby hill. He had violated 'prescribed norms'. In other words, he had deprived transporters their ferrying opportunity and contractors their civil works one. Vested interests worked overtime. Elango was suspended from office under Section 205 of the Tamil Nadu Panchayat Act [TNPA].

He was devastated. He thought he had made a novel environmental, economic and development statement -- and he had been thrown out and humiliated for his pains. Why had he not heeded those that had said politics was a cess-pool? Why had he abandoned a promising career? What had he to show for Sumathy's support? He went into a deep depression. He thought of quitting.

The Gandhi moment:

Sumathy left him alone for a few days and then made one of her rare visits to Kuthambakkam. She held him and asked him if that was the end of his passions? 'Are you going to give up because of this one set back?'. She had brought a book for him, 'Satthia Sodhanai', a Tamil version of Gandhi's 'My Experiments with Truth'. She left him alone again.

Elango says though he had heard of the book he had not read it. His predicament gave it an immediacy as he read it now. It seemed written for him. He understood the mind of a dogged man who had faced greater odds. The book taught him grit. Within a few days he was in Chennai calmly telling the Secretary to the Government: "No, I will not sue you but sit in protest until you convene a plenary session of my village. Let your charges be read out, my defence heard and the villagers decide my fate." He contacted the press. On Jan 10, 1999, 1300 people gathered and Elango defended himself. Before the sun set on the day long trial, the Government sent in an order revoking the suspension. The entire village had rallied behind him. "I understood Gandhi that day," he says. "First be truthful, then be fearless."

There has been no looking back since then. Elango was re-elected with a huge majority at the end of five years. The graft mafia ran away. Officials backed his approach of cutting out contractors and employing locals instead. As he created jobs, liquor menace receded. He had always paid above the market average, currently Rs.70 per day; and most revolutionarily, precisely the same for women.

In 1992, the village built itself a grand school with its own funds and labour. Today 850 boys and girls study in it, only 650 of them Ralegan children. In the boys' hostel are 250 kids from all over Maharashtra. To be eligible they need to be drop-outs; if they have failed in their studies their chances of admission are better. Yet, over 90% of the children pass high school. The school has science laboratories, computer courses and a big library. There's a retired army sergeant who drills fitness into them. Kids rise at 5.30 am for a shrieking, mass run through the village. The school has vast play grounds. Children run a nursery, and actively plant and care for trees. Girls are taught to swim, to ride bicycles and lately bikes. Anna believes that development in society isn't possible without women playing an active part.

Main media knows Anna mostly as an agitator. He is a good one too. He will fight for the village's right to every sanctioned scheme. Villagers will not pay a bribe. They will collar and expose any bribe seeker. Anna's reputation is such that the Government trembles when he demands action and transparency. [Read this story.] Awards and cash have come his way. All the prize money -- over Rs.19 lakhs-- has gone into running his Vivekananda Trust, that awards an annual cash prize of Rs.25,000 to a village level leader. Ralegan has become a legend. There's a steady stream of politicians and leaders who come to see for themselves. Buses drone in constantly bringing villagers. Some on day trips, and some for weeks long courses. There is a formal Training Centre. When he is in town --which is rarely, these days-- he will receive and talk to anyone, sharing his ideas and vision.

Cloning Ralegan:

We are in luck. He is 'in'. He is a short, compact man with an earnest face. He sits cross legged on the floor and has all the time for you. His simplicity and readiness are slightly unnerving. You expected a greater reserve from a man who is widely venerated. Soon you know why he lacks it. "As long as there is 'my' and 'mine', there is sadness," he says. "When you define your family in narrow terms, the contrasts within it and without will be stark. So there will be sadness. But as soon as you define 'family' in inclusive, wide terms all sadness disappears."

Why is this emphasis on not consuming liquor, tobacco or meat? Doesn't it amount to coercing people?

"You can begin where you want in development," he says."But at some point or the other you have to address these issues. They come in the way. They are connected with issues of health, economics, education, responsibility and family harmony. In Ralegan we got them out of the way quite early. Others will have to get them out of the way later, if they envy Ralegan and want to emulate it."

School in home town:

He now diverted his attention to his home town of Rampur Manjha in UP. It had no school. Work with Jai ramji has always been brisk and speedy. The foundation stone of this school was laid in 1964; it started functioning as Middle School in the same year and as High School by the end of 1965. It is the only High School for the surrounding villages. He wants a college there by 1970. He needs Rs.35,000 for that and is today busy collecting that.

All these institutions --the Hindi High School, the Jhunjhunwalla College and the High School in UP are the embodiments of people. The humblest of people have put their efforts to bring up these institutions, donating from a paisa upward. This reminds one of a legend from Ramayana, from whose lands Jai Ramji hails. While Lord Rama was constructing the bridge between India and Lanka, along with the monkeys came the squirrels to put in their efforts

Jai Ramji is 72 today. Even at this age, his energy is unflagging, his cheerfulness is contagious and his faith boundless. Faith, both in God and the goodwill of his fellowmen. Nor has his capacity to dream diminished. Above all, is his ability to fulfil those dreams. His dream at present is a Hindi University. And he has confidence he will live a hundred years to complete his mission.

He toils still:

One question remains. What does he do for his own living and that of his family? He married at the age of ten. His life has not been a bed of roses. He lost two of his sons, one of them leaving behind a wife and a son. As a postman of 32 years service, he never had an occasion to give an explanation for a lapse on his part. After retirement, he went into the manufacture and sale of phenyle, often pulling a wheel cart himself through the streets of Ghatkopar along with his son, making door to door calls. He is also an LIC agent, selling life insurance. His only surviving son is married and settled. Himself, his wife, his daughter-in-law and grandson are together in the house. In these days of graft and corruption, the example of Jai Ramji stands out -- a rare apostle of determination and faith in modern age.

Movie and media splash: