|

|

|||

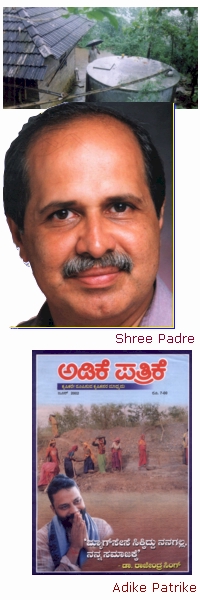

Shree Padre first created a farmers' network - and has now turned to preach water harvesting. |

|||

|

The life of Shree Padre has flowed in surprising ways and has today made him an evangelist for water harvesting. Throughout western Karnataka and north Kerala his passion for water conservation has energised people to action. RWH [rain water harvesting] is now a fashionable buzz-word and in those parts you are not 'in' if you did not do something for RWH! People are getting inventive with their solutions, sharing them and forming clubs. And Shree Padre continues his long trips in aid of his cause, like an ideas-pollinating bee. A country journalist: Shree Padre's village is tucked away some kilometers off the Mangalore-Kasargod highway. It is one of the several that nestle amidst beautiful hills and valleys of the lower Western Ghats. Being tucked away, these villages have retained many old world values like family life, self discipline, gentleness, hard work, honesty, social harmony and non violence. The green, wooded environment may not make you wealthy but you would certainly be contented. For all the inroads man has made into the forests here, much beauty remains. The widespread crop is arecanut -- yes, the betel nut that the sub-continent loves to chew. Because the price of arecanut swings wildly [it is now depressed] a Dakshina Kannada farmer is ever eager for usable information. And that information -- for a long, long time-- was not easy to come by. Shree Padre was born in 1955 into a farming family whose land holdings had recently diminished consequent of land reform laws and division of Kasargod district between Kerala and Karnataka. He went to Puttur --the nearest town-- for his studies and graduated in Botany and then did a Masters in History. He then took to journalism as a freelancer in English and Kannada. His human interest stories began to be published in a wide number of magazines. A crisis and a novel response: For the farming community around Padre's world, 1985 was a crisis time: the price of arecanut ['adike', in Kannada] had fallen -- farming incomes plummeted. The 'All India Areca Growers Association' centred in Puttur decided to take some action. First of all it co-opted other professionals and got them to study farmers' problems and suggest solutions. Shree came in as a journalist and the idea of a newsletter to bring farmers together was born. It was modestly funded and was intended to be a simple news bulletin. After he had published a few of these bulletins, Padre diagnosed the real problem: farmers lacked information and channels of communications. The only farming information they were getting was output from scientists and officers of the Government and ad-driven magazines' writers. It was one way 'announcement - jounalism' which had no room for feedback. Often he'd find the unethical practice of brandnames of farm inputs mentioned. Was it all to help the farmers solve their problems or to help market goods to them? He concluded: "Those who grow never write; those who write don't grow." There was a need for a magazine which was written by farmers for farmers. It would publish only proven practices, allow space for posting queries and sharing solutions and only carry advertisements that cast no shadow on editorial content. Padre wrote an elaborate proposal and presented it to the Association. They welcomed the idea but wondered if depending on farmers for content would sustain a monthly. But they decided to give it a try and 'Adike Pathrike' [-Areca Magazine] was born in 1988. The first issue was released by Dr. Kota Shivarama Karanth, a beloved son of Karnataka arts - he had seen the point of it. Jounalism that delivers: Naturally the reponsibility fell on Padre. He calls it 'self-help journalism', a pioneering concept. Till then farmers had felt a tremendous inferiority: "We know nothing about science and all that is required to making farming 'modern'." Padre began to travel miles visiting them and telling them that they were heirs to a great tradition and a knowledge system. At least whatever has worked for them is totally proven in the real world, which cannot be said about a scientist's work. He assured them that their notes would be cleaned up and rewritten before publication. He conducted several 'writing workshops' for farmers who would be jounalists. [These became so popular that many scientists began to attend them!] He urged farmers to post their problems. And respond when they had a solutions to others' problems. He always gave full contact details and phone numbers, so they could call each other up. To avoid publishing all that came in, he began to 'commission' chosen farmers with story ideas. Some times scientists would send in contributions and confidently expect to be published. But at Adike Pathrike that was not automatic. Often the scientist would receive a polite request to state where in the field the idea/practice had been proven. Well, Adike Pathrike has been a run away success. In 14 years it has never missed an issue, never been delayed and boasts a readership of 75000. Priced at Rs.7 and supported by ethical advertising it manages to break even. Farmers have old issues bound as reference volumes. The magazine has a cult following among farmers and has triggered numerous clubs to implement ideas that call for group action. Shree Padre has written a fine, long essay on this unique adventure. The objective was 'Krishikara Kaige Lekhani' -- 'Put the pen in farmers' hands'. That has been attained. Padre next turned to another problem with communication in agriculture. Many farmers don't read, let alone write. And some that can, won't care to write in. How to include them? Thus was born the idea of 'Samruddhi'['Prosperity']. It is a group that meets once a month in Puttur. Members arrive with plant material and seeds to show and exchange. During a day long meet all communication is by voice and vision only! Since 1993 when it began, the membership has grown to a 150. Often they form groups that bus away on field trips to discover and learn. It is an enthusiastic idea exchange. To the source of it all: In 1995 Adike Pathrike decided to start a series on ways people conserve water. Expecting it to be a rich source of content that would pour in, Padre gave the series a grand title: "A 100 ways to save water". Then he waited amidst a deafening silence! Had ample rainfall, electricity and borewells made farmers forget ancient ways with water? Looking back that was the defining moment in Shree Padre's life. Enquiries with government departments revealed they had little information on how or where RWH was being practiced. When he turned to non-governmental sources however, there was reason for optimism. Padre quickly understood the seriousness of the issue. The magazine was maturing and could afford a paid editor. He left it to a team and turned almost exclusively to propagating conservation of water. He began to document traditional ways and world-wide practices used to conserve water. And he began to drown in the subject. "My own farm has 'surangas', man made caves on the hill side into which water drips, forms a shallow pool and flows by gravity into my farm. In many farms 'madakas' --which are strategically located percolation tanks -- have been abandoned. In Ahmedabad, there were 10,000 'tankas' or huge basement storages that are now in disuse. [Click for a picture] In one they recently found water that was 50 years old-- when tested it was found perfectly potable. Why have we suffered such a disconnection with sustainable ways? We seem to have developed a perverse notion of 'modern science' and lost our esteem for proven, sustainable methods," he says. Saving water has become a passionate mission for him. Gathering material for the magazine's series took him to many places [- with financial support from Dr. L C Soans,a farmer of Moodabidri and Nagarika Seva Trust] to observe field practices . As examples began to be published, reader awareness quickened. Then came a 180 page 'how-to' handbook in Kannada called, 'Nela Jala Ulisi'. This book has emerged as a standard handbook. Adike Pathrike has so far published 75 success stories and their numbers --in the last couple of years-- have accelerated. Padre then began conducting day long workshops where he makes a slide presentation of RWH success stories. "I constantly stumble upon a farmer or a householder who has devised a novel method," says Padre. "They are often simple but suited to the situation. There is a palpable enthusiasm across 5 districts of Karnataka. People seem involved in trapping every drop of water that falls on their property!" Padre's workshops are very popular and draw many people. Village groups cheerfully subscribe and pay the cost of Padre's travel and incidental expenses. Since 1996 he has conducted more than 250 workshops taking his message to an estimated 20,000 people. Each workshop has called for an average of 75 km of travel to remote villages. Amidst all this he writes regular weekly column on the subject in Vijaya Karnataka, a Kannada daily. There have been a series of books too - five in Kannada and one in English. The excitement has led to results. Idkidu [see box] is but a sample. Another evangelist -- Rajasekhar Sindhoor of Savanur, Haveri Dt., Karnataka-- has arisen and is reaching new audiences. Everywhere people are hunting down water!Indeed, RWH could be read as Rain Water Hunting. in Karnataka Padre and others are turning it into a widespread, serious, competitive sport. Water is a war and peace issue. Not for nothing has it been said that the coming wars will be over water. The squabbles between Karnataka and Tamil Nadu over Cauvery water is a curtain raiser. What gives us heart is the work of people like Shree Padre. He says simply: "If water scarcity splits people, rain harvesting brings them together". In a good part of western Karnataka he has brought thousands of people together -- through water. ___

Shree Padre's book "Rainwater Harvesting" is an overview of the methods that can be adapted. It contains success stories from around the world. 116 pages; US$ 6 [or Rs110 within India] from Altermedia, Thrissur, India or from their website. ___

Shree Padre Post : Vaninagar Via : Perla - 671552 Kerala- India Phone : 0825 - 647234 ; 0499 - 866148 E-mail : shreepadre@sancharnet.in ___

October,2002

|

|

||